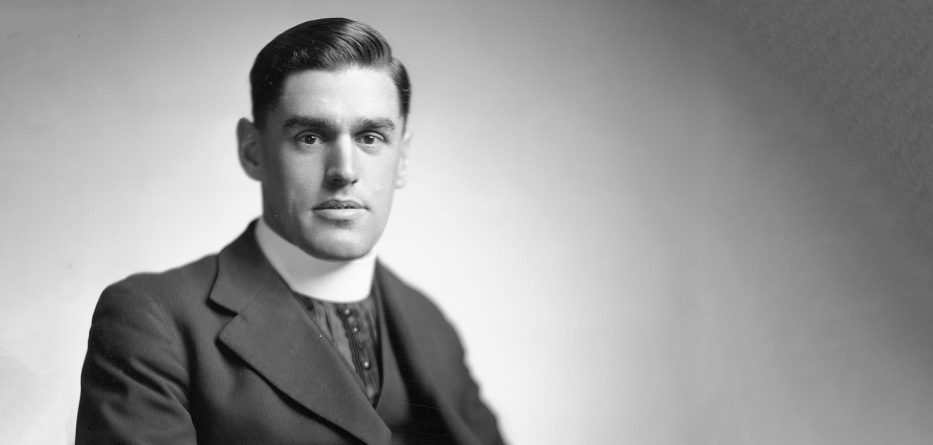

He’s little known among Catholics outside New Zealand, but some consider this handsome young priest to be a contender for their country’s first official saint, writes Peter McCleave.

Francis Vernon Douglas is a name largely unrecognised in Australia. He was born in New Zealand, of an Australian father and Sligo mother. He was part of a large Catholic family that, like many before and during the Great Depression, struggled to survive.

He finished school at 14 in 1924, and in 1925 began work with the Post and Telegraph Department as a messenger boy. He subsequently entered the-then National Seminary, Holy Cross, at Mosgiel – a cold and isolated, but picturesque, town on the Taieri Plains of the original Otago Province in the lower South Island of New Zealand.

Douglas was ordained priest at St Joseph’s Church, Buckle Street, Wellington, on 29 October 1934 by Archbishop Thomas O’Shea. His eldest brother had already entered religious life by joining the Marist Brothers, and an elder sister was a nun at the Convent of the Sacred Heart in Rose Bay, Sydney.

Following ordination, he worked as a curate in several parishes, but his aspirations lay elsewhere.

From 1933, when two of its priests had visited New Zealand and an open letter appealing for recruits had been distributed, Douglas had felt drawn to St Columban’s Foreign Mission Society – popularly known as the Columbans.

The congregation had been founded a mere 17 years earlier in Ireland in 1916 to evangelise China. In 1936 Douglas went to Australia to join them and train for a year at their seminary in Melbourne.

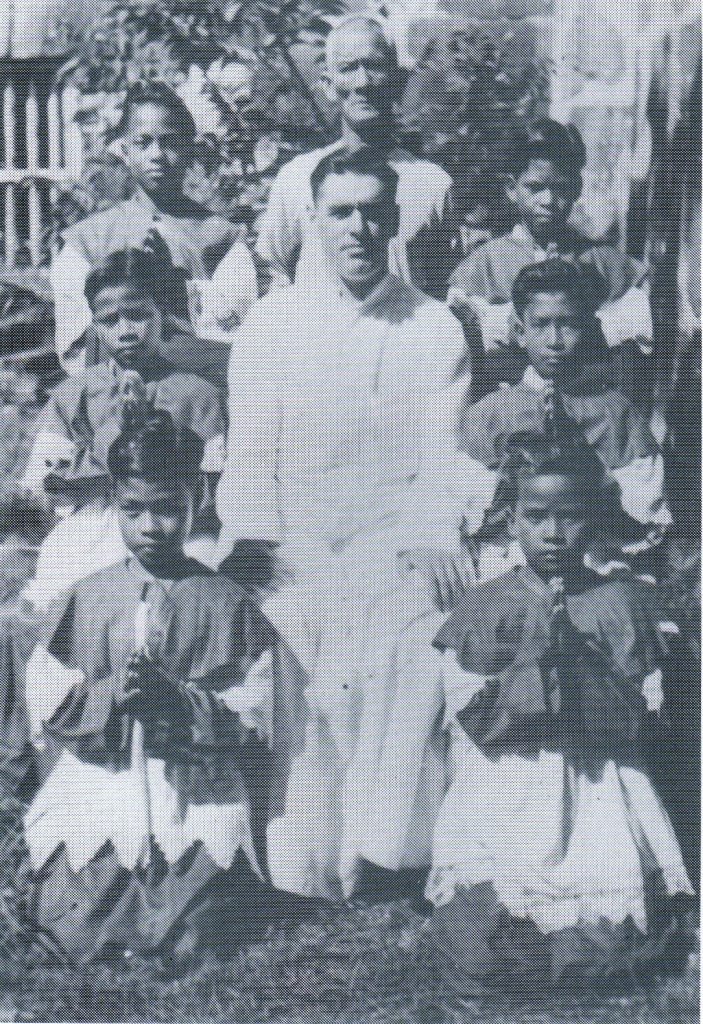

On completion he was posted to the Philippines and worked in a remote area some distance from Manila.

As a result of the Japanese invasion of China in 1937 the Columbans began posting missionaries elsewhere in Asia.

Late in 1938 Douglas was appointed to Pililla, a fishing town near Manila in the Philippines.

Conditions were harsh, and he struggled to combat religious indifference among his parishioners, for the most part nominal Catholics.

His difficulties increased after the Japanese occupied Manila in January 1942. The Japanese onslaught was initially intense and the Philippines was quickly overrun.

Still, the conquerors were, at first, half-heartedly tolerant of the expatriate Christian missionaries who stayed at their posts.

But they became less patient after the Allied counter-attack on Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands in August 1942.

As opposition slowly built up, local groups acted as guerrilla units against the occupying Japanese, who treated the conquered with little if any regard. Starvation, torture and execution became common.

As the war progressed and the Japanese themselves came under threat, the atrocities increased, together with their suspicions of the non-native occupants.

Douglas reluctantly obeyed the restrictive rules imposed by the Japanese until July 1943.

In that year, he felt obliged to visit some American guerrillas in the nearby mountains who claimed to need his priestly services.

To his anger he discovered that they merely wanted fresh company; he had been a victim of what proved to be a tragic hoax.

The trip aroused suspicions that he was spying for the resistance forces, and on 24 July 1943 Japanese soldiers took Douglas from Pililla to Paete to interrogate him.

Unwilling to divulge confidences or to break the seal of the confessional, he refused to answer questions. For three days he was tortured and beaten, then on 27 July he was taken away. He was never seen again. A Captain Shikioka subsequently charged with mistreating Douglas was never apprehended.

This is where, for me, the story becomes personal.

His last parish appointment before the Columbans was to St Joseph’s in New Plymouth, NZ. St Joseph’s occupied an amazing site in the town. On a high land mass at the top end of the town was the weatherboard church, church hall, presbytery and large convent.

Usually in early Australia and NZ, the prime site was where the Church of England stood (note Hobart) but here it was different. However one does not distract from the fine beauty of the historic Anglican Church of St Mary in New Plymouth (now a Cathedral), which is worth a visit.

Sadly the old Catholic church buildings have now gone, replaced by what some call modern architecture.

At St Joseph’s, Father Douglas was curate to the incumbent Father Minogue. Vernon, as he was and still is commonly known, was responsible for the Boy Scouts: St Joseph’s Scout Group. My father was Vernon’s scout master and closely associated with him and Father Minogue.

The death of Vernon was extremely felt in New Plymouth, especially among the Catholic community. His torture whilst tied to a baptistery was a horror.

I learned of this from my father soon after the end of the War. Other Catholics knew it as well and came to regard it as an example of the meaning of holding office as a Catholic priest.

At this time and distance, so much is unknown – especially where the body of Fr Vernon Douglas now lies.

The prospect of launching Vernon’s cause for beatification and canonisation has arisen among New Zealand Catholics from time to time but it awaits more intense interest and awareness.

In 1959 his name was given to a new boys’ secondary school at New Plymouth, Francis Douglas Memorial College, and thus serves as an ongoing expression of what he stood for and did.

Further information exists for those who seek more details. A reprint book on his life will be issued this year.

Peter McCleave is a Retired Medical Practitioner and Administrator. This article includes information from NZ Government sources.

With thanks to the Columbans and The Catholic Weekly.