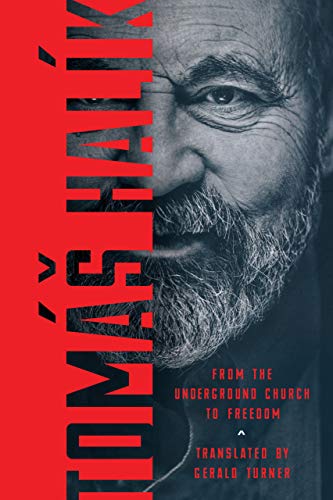

Book Review – Tomáš Halík : From the Underground Church to Freedom : University of Notre Dame Press, Notre Dame, Indiana 2019.

Tomáš Halík is a Czech Roman Catholic priest, philosopher, theologian and social scientist. He has also practised for many years as a psychotherapist. Currently he is Professor of Sociology at Charles University and Pastor of the parish of St, Salvator in Prague. In 2014, he was awarded the Templeton Prize, which honours a living person who has made exceptional contributions to affirming life’s spiritual dimensions, either through insight, discovery or practice.

Previous winners of the Templeton Prize include Charles Taylor (2007), Martin Rees (2010), the Dalai Lama (2012), Desmond Tutu (2013), Rabbi Jonathan Sacks (2016) and sadly, in the light of recent revelations, Jean Vanier (2015). So, Halík is in excellent company.

From the Underground Church to Freedom. Image: Amazon.

From the Underground Church to Freedom is a spiritual autobiography in the tradition of St. Augustine’s Confessions, John Henry Newman’s Apologia Pro Vita Sua, and Thomas Merton’s Seven Storey Mountain. It is, however, more comprehensive than any of these in so far as it is a detailed record of his whole life from his birth and baptism in June, 1948, to his current involvement not only in the Church but also in Czech politics and academia. Further, it is more than a record of the significant events in which he has played a not inconsequential part leading up to, and following on, the Czech “Velvet Revolution” in November/December 1989. Like Augustine’s Confessions, to which Halík specifically alludes, it is the development of his spiritual life and his personal reactions to these significant events that are even more revelatory than the account he provides of the underground meetings and movements that catalysed the student-led revolution and transformed the nation from a one-party Communist state into the Czech Republic.

Previous to reading Halík’s book, I had been reading Helen Garner’s Yellow Notebook: Diaries, Volume 1: 1978-1987. It is not only that the two books are partially contemporaneous, but there is an immediacy and reflective quality in Halík’s autobiography that invites comparison with Garner’s diary musings, disjointed as her entries inevitably are.

Indeed, the most interesting, challenging and evocative dimension of Halík’s autobiography is his intensely personal reflections both on the progress and development of his own spiritual life and the effect that the people that he meets and the events in which he is involved have on that development. The title of the first chapter: “Are you writing about yourself?”, the title of the second chapter: “My Path to Faith”, and the title of the fourth chapter: “My Path to Priesthood”, indicate the priority that Halík places on his own spiritual life. Later chapters: “The Experience of Darkness “and “On the Threshold of Old Age”, and the concluding chapter: “A Journey to Eternal Silence”, continue this emphasis. No doubt his own extensive practice as a psychotherapist assists him in his scrutiny of his own motivations and reactions, but he does not let the scientific and the medical either obtrude on the spiritual or minimize its dimensions or significance.

There is close analysis, but no easy reductionism.

I must confess that I found the chapters leading up to the Velvet Revolution in 1989 marginally more interesting than the account of Halík’s experiences in the subsequent thirty years of the Czech Republic. This was not only because the rigours under which, and crisis in which, Halík worked, first of all as a lay leader and then as a priest in the underground Church were by nature of their secrecy and danger more enthralling.

Evading the secret police and exploiting the Communist Government’s concessions to visit England, Germany and Rome certainly added a quasi- romantic dimension to the record of Halík’s experiences during those years. His account of visits subsequent to the Velvet Revolution to countries previously interdicted the Communist Government inevitably pales in comparison with these previous exploits. While they were no doubt necessary and important to give credibility to Vaclav Havel’s new regime, they are redolent more of the confidences of a politician or statesman than the spiritual and personal reflections of a priest. Even the concluding chapters where he reviews his lifetime experiences, and where the reader might have expected deep insights into an extraordinarily rich life, there is not the same sense of struggle and spiritual development as that which characterised the earlier chapters. It was as if Halík, now into his seventies, was resting on his laurels.

Despite this somewhat disappointing conclusion, however, this is certainly a book well worth reading not only for the historical events which it reviews from a unique perspective but also because the account Halík gives of his own spiritual development invites the readers to reflect on their own. Even for this alone I have no hesitation in recommending From the Underground Church to Freedom to a wide readership.

Fr Bill Uren SJ AO is scholar in residence at Newman College, Parkville.