Homily for the Twenty-Seventh Sunday in Ordinary Time

Readings: Isaiah 5:1-7; Philippians 4:6-9; Matthew 21:33-43

4 October 2020

For the fourth Sunday in a row, our gospel is a parable from Matthew. Three weeks ago, it was the parable of the unforgiving debtor who was forgiven a massive debt only to take it out on his companion who owed him little. Two weeks ago, it was the labourers in the vineyard, with those who worked only one hour at dusk receiving the same pay as those who had worked all day under the hot sun. And last week, it was the two sons – one of whom said Yes but didn’t, and the other of whom said No but did. Actions speak louder than words.

Listen at https://soundcloud.com/frank-brennan-6/homily-41020

Today it’s the parable of the wicked tenants in the vineyard. The Matthean community in the decade 80-90AD when Matthew was composing his gospel were probably ‘a once strongly Jewish Christian church that had become increasingly Gentile in composition’.[1] They’d have been well familiar with the prophet Isaiah’s description of the vineyard in today’s first reading. In Isaiah’s account, the owner has done everything right, investing all he could, hoping to produce superb grapes, and presumably the finest wine. But the vineyard produces nothing but sour grapes. So he abandons the vineyard completely. It will lay waste, unpruned, undug, and overgrown. The prophet Isaiah leaves the chosen people in no doubt: the Lord’s vineyard is the House of Israel and the people of Judah. Instead of justice and integrity, only bloodshed and distress are to be found. By their fruits you will know them. By our fruits, individually and collectively, we will be known.

With this backdrop, Matthew takes the story of the vineyard and transforms it into a very violent allegory. This time the focus is not the vineyard itself. This Matthean vineyard, unlike Isaiah’s, seems to be producing fine grapes, the makings of fine wine. This time the problem is the tenants to whom the owner has leased the vineyard. At harvest time, the owner’s servants go to fetch the owner’s share of the fruits (which would have been most of it) and the tenants thrash, stone and kill them. So the owner sends another batch of servants who suffer the same fate. If this were anything but a dramatic allegory making a very blunt point to the listeners, the next step would surely not have occurred. The owner has already lost two sets of servants. Naively or idiotically or in the most unworldly manner, the owner sends his son saying, ‘They will respect my son.’ No they don’t. This is the son and heir. The tenants think that by escalating the violence, they might come to inherit the vineyard once the owner is dead because they will have disposed of the son and all the servants.

The listener takes pause. Hang on. This owner is not naïve and idiotic. This owner is not just any vineyard owner. This owner is Yahweh. The son is Jesus the Son of God. The Matthean community gathered half a century after Jesus’ death affirm him as the Son of God. In Matthew’s gospel, the centurion at the cross witnessing Jesus’ death had proclaimed: ‘In truth this man was son of God.’ When John had baptised Jesus, there was that voice from heaven, ‘This is my Son, the Beloved; my favour rests on him.’ These same words were repeated in the hearing of Peter, James and John at the Transfiguration.

Jesus has told this story to the chief priests and the elders. He asks them what they think the owner will do to the tenants when he comes. The Matthean community would have seen the chief priests and the elders condemning themselves out of their own mouths, given the way they treated Jesus sending him to his death by crucifixion. The chief priests and elders answer: The owner ‘will bring those wretches to a wretched end and lease the vineyard to other tenants who will deliver the produce to him when the season arrives.’ Jesus tells the chief priests and elders very bluntly: ‘I tell you, then, the kingdom of God will be taken from you and given to a people who will produce its fruit.’

One scripture scholar Jack Dean Kingsbury says, ‘It is the aim of Jesus in this parable to make God’s evaluative point of view concerning his identity his own and to confront the Jewish leaders with it. This aim of Jesus is not lost on the Jewish leaders. They understand the metaphors he has used and the claim he has raised that he is, in the sight of both God and himself, the Son of God whom they will kill’.[2]

The hearers of Matthew’s gospel, whether they be the first hearers of the first century or us of the twenty-first century are warned as were the chief priests and the elders: Don’t think the kingdom of God is yours simply because you are members of the Chosen People, or because you are religious leaders, or because you are members of the Church. Don’t think the kingdom is denied to those who are not members of the Chosen People or those who are not religious leaders signing up to the Vatican line of the day, or those who are not members of the Church. Jesus came and revealed himself as the Son of God so that the kingdom might be denied any one righteously depending only on group membership or past observances, and so that the Kingdom might be taken from them and given to a people who will work the vineyard, produce its fruit, and share the profits equitably. The story shocks the chief priests and elders because they are told to look to the stones they have rejected, and they will have a good chance of identifying the keystone of the kingdom to come. We and our church leaders are being told the same thing, today and everyday to come.

There’s a lot of violence in today’s gospel – the tenants stone, thrash, kill and aim to steal inheritance; the owner brings the lot and the lives of those tenants ‘to a wretched end’. We have observed a stark instance of violence, disorder, disrespect, irrationality, and the ruthless exercise of power during this past week with the first of the US presidential debates. I have not spoken to anyone, regardless of their politics or party affiliation, who was edified, assisted, impressed or inspired by anything they saw or heard in that internationally televised collapse of civic discourse and reasoned argument.

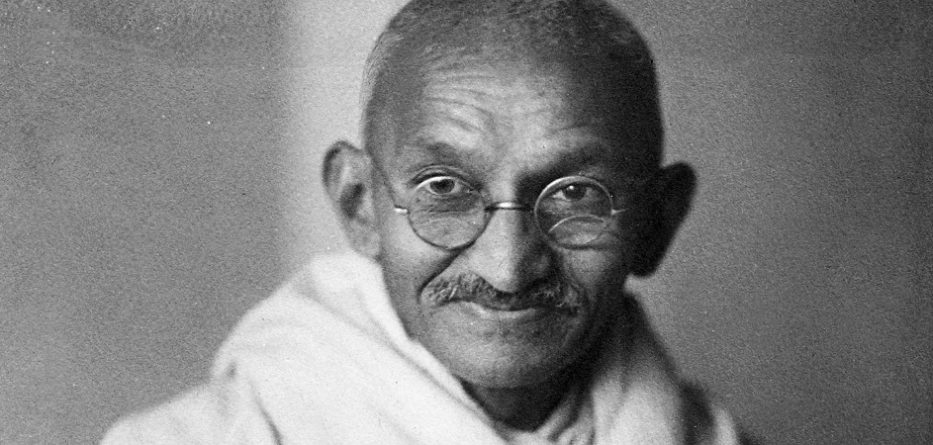

What place is there for violence and disrespect of the one who is Other in trying to produce the fruit of the kingdom? On Friday we marked the International Day of Non-Violence, the 151st anniversary of the birth of Mahatma Gandhi. Like any of us, Gandhi was not perfect, and he had his internal inconsistencies, but he dedicated himself to non-violence. He became the embodiment of non-violence. He insisted: ‘When non-violence is accepted as the law of life, it must pervade the whole being and not be applied to isolated acts.’

After he undertook a 3-week fast for Hindu Muslim unity, he wrote: ‘The more efficient a force is, the more silent and the more subtle it is. Love is the subtlest force in the world.’ When Congress President, he wrote: ‘Love is the strongest force the world possesses and yet it is the humblest imaginable.’ When publishing his autobiography, he wrote: ‘The force of love truly comes into play only when it meets with causes of hatred.’

When reflecting on the dropping of the atomic bombs, the 75th anniversary of which we marked in August, he wrote: ‘The moral to be legitimately drawn from the supreme tragedy of the bomb is that it will not be destroyed by counter-bombs even as violence cannot be by counter-violence. Mankind has to get out of violence only through non-violence. Hatred can be overcome only by love.’

When visiting India, Pope John Paul II said that Gandhi pointed us ‘to a future where our deep longing to pass through the door of freedom will find its fulfilment because we will pass through that door together. To choose tolerance, dialogue and cooperation as the path into the future is to preserve what is most precious in the great religious heritage’ of humankind.

Gandhi has something to teach us Christians of the twenty first century. If we are to pass through the door of freedom together, if we are to produce the fruit of the kingdom, and if we are to display justice not bloodshed, and integrity not distress, we need to be good tenants of the vineyard entrusted to us, thanking God that the vineyard is a gift bestowed on us for the good of the world. And we need to forbear, even in the name of truth, from commencing or furthering the cycle of violence which ends in bloodshed and distress. Let justice and integrity be our hallmark – inheriting, proclaiming and sharing the good news of the kingdom to come. Subtle, strong love overcoming hate is the ultimate fruit of this vineyard.

[1] Raymond Brown, Introduction to the New Testament, Doubleday, 1997, p. 213

[2] Kingsbury, J. D. “The Parable of the Wicked Husbandmen and the Secret of Jesus’ Divine Sonship in Matthew: Some Literary-Critical Observations.” Journal of Biblical Literature 105 (1986) 643–55 at p. 653

Fr Frank Brennan SJ is the Rector of Newman College, Melbourne and the former CEO of Catholic Social Services Australia (CSSA).