The Feast of The Holy Family of Jesus, Mary and Joseph

Readings: Genesis 15:1–6, 21:1–3; Psalm 127(128):1–5; Colossians 3:12–21; Luke 2:22–40

27 December 2020

“Meanwhile, the child grew to maturity.” – Luke 2:40

The Holy Family is uniquely centred on the fulfilment of the greatest promise made by God to the human race, namely, the sending of our Saviour. The entire focus of this family was on the person of Jesus from his very annunciation to his infancy, childhood, adolescence and manhood. Meanwhile, Jesus was focused on his heavenly Father as he gazed into the faces of Joseph and Mary.

Both the first reading and the Gospel contain stories of promises made by God to human beings. First, we read about the promise made to Abram that he will have a son from his own flesh and blood. Secondly, we read about the promise made to the old man, Simeon, that he would not die before he set his eyes on the Christ of the Lord. God kept both promises.

We do not know how many years had passed before the promise made to Simeon was fulfilled, but for Abram it was 25 years! We can only imagine how, with the passing of each day, both men would have longed for God to fulfil his promise to them. Perhaps they had moments of doubt? The Holy Spirit would have reminded them of the promise. With the passage of time, they learned to hope in the fulfilment of these promises.

For us, the Holy Family is a powerful sign of living hope that God always keeps his promises. If we centre our lives upon his Son, we too will find a hope that springs eternal.

May we, like Mary and Joseph, know how to focus upon Jesus as the centre of our families and adore the Father through him. Amen.

Fr Mark de Battista

Artwork Spotlight

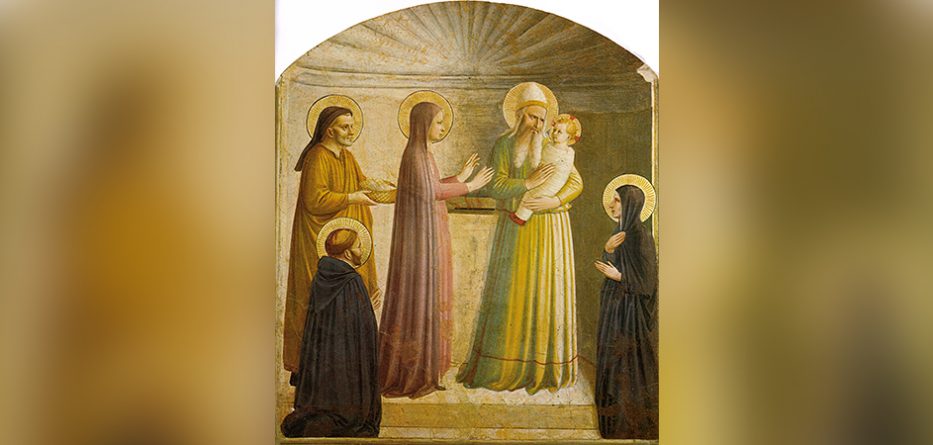

Presentation in the Temple – Fra Giovanni Da Fiesole (Known as Fra Angelico) (1390–1455).

“Presentation in the Temple”, c. 1437–45. Fresco, 158 x 136 cm. San Marco, upper storey, dormitory, cell No. 10 (east corridor), Florence Italy. Public Domain.

It has been written of Fra Angelico that: “It is impossible to bestow too much praise on this holy father, who was so humble and modest in all that he did and said and whose pictures were painted with such facility and piety” (Lives of the Artists, Giorgio Vasari). He was probably born about 1390–1395 as Guido di Pietro, and by the 1430s was already one of the leading artists in Florence. Just before 1423, Guido donned the habit of the Dominican friars in the convent at Fiesole just outside Florence, taking the name Fra Giovanni (Friar John). In 1436, he was one of a number of friars from Fiesole who moved to the newly-built friary of San Marco in Florence, the building of which had the patronage of Cosimo de’ Medici, one of the most powerful members of the city’s government, and founder of the dynasty that would dominate Florentine politics for much of the Renaissance.

It was in this convent that Fra Angelico painted his famous Annunciation and decorated the cells of the friars. He came to the attention of the pope, who asked him to decorate his private chapel in the Vatican with scenes from the lives of St Stephen and St Lawrence. Fra Angelico died while in Rome in 1455, and is buried in the Church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva. Pope John Paul II recognised the humble friar’s sanctity by beatifying him in 1982. From various accounts, we learn of Fra Angelico’s devout and ascetic life as a Dominican friar, following the dictates of his order and caring for the poor. It is said he was always good-humoured. He always prayed before beginning a work and wept when he painted the Crucifixion. “He who does Christ’s work must stay with Christ always,” he said. During the Great Jubilee of 2000, Pope John Paul II declared him the patron of all artists.

The scene we are contemplating can be found in Cell 10 of St Marco’s Convent in Florence. There are 44 cells, and Fra Angelico had one thing in mind—the scene in each cell was meant to inspire the resident’s devotion. What attracts me to this particular fresco is the “dialogue” between the high priest and the divine Child. Look carefully at their eyes. There is a direct contact which makes you wonder what they were saying to each other. Our Lady is in the act of presenting the Child, St Joseph behind her with two turtledoves—the offering of the poor. Each Jewish family had to “buy back” their firstborn son in thanksgiving to God who had preserved their ancestor’s firstborn on the night of the Passover. Functioning as intermediaries between the viewer and the holy figures depicted are the Dominican St Peter Martyr (frequently included in Fra Angelico’s paintings) and Blessed Villana, a Florentine holy woman of the 14th century.

While the scene seems peaceful enough, the presence of St Peter Martyr reminds us of the consequences of following this Child. The whole event of this day is actually harrowing. The old man Simeon runs into Mary either on her way to the Temple or on her way back. He would have recognised her easily enough for she had spent most of her youth studying there, if the tradition is correct. His surprise is that it is her Child who is the Saviour the Holy Spirit promised he would lay eyes on before his death (maybe this is the line that prompted Fra Angelico to emphasise the eye contact between the Child and the high priest.) Simeon’s meeting with Our Lady is almost a second Annunciation, for now he spells out her future. Her Child will accomplish his mission only through misunderstanding and sorrow. Jesus’ invitation to follow him will be rejected. His teaching will be like a sword that would split the world in two, and that sword will also pierce his mother’s heart.

And Mary will not have long to wait to see the prophecy fulfilled. She returns to Nazareth to witness the unprecedented horror of the murder of her neighbour’s children. She becomes the mother of a hunted God—a God condemned to death while still a Child. She escapes to Egypt, but it only means that her Son has had his execution postponed. At Cana, when she calls on her Son to help an embarrassed young couple, he answers that a miracle will enrage his enemies. He will accede to her request, he says, but only if she accepts the consequences with him: “What to me, to thee,” the Greek literally says.

Contemplation of this scene of the Presentation prompted Pope Paul VI to write: “The Church … has detected in the heart of the Virgin … a desire to make an offering” (Marialis Cultus, 20), an offering of herself—but in sacrifice. And, her Son’s sacrifice is hinted at in the swaddling clothes in which he is bound, reminiscent of the shroud to come.

Monsignor Graham Schmitzer

Fr Mark De Battista is the administrator of St Patrick’s Parish in Port Kembla. Born in 1970, his family migrated to Australia from Malta in 1978. He was raised in a strong Catholic family and was ordained a priest for the Diocese of Wollongong in 1995. From 2003–2007 he served in university ministry in the USA (Illinois and Colorado). From 2010–2016 he went to Rome for studies in sacred Scripture. He has served in several parishes in the Diocese of Wollongong.

Monsignor Graham Schmitzer recently retired as the parish priest at Immaculate Conception Parish in Unanderra, NSW. He was ordained in 1969 and has served in many parishes in the Diocese of Wollongong. He was also chancellor and secretary to Bishop William Murray for 13 years. He grew up in Port Macquarie and was educated by the Sisters of St Joseph of Lochinvar. For two years, he worked for the Department of Attorney General and Justice before entering St Columba’s College, Springwood, in 1962. Fr Graham loves travelling and has visited many of the major art galleries in Europe.

With thanks to the Diocese of Wollongong who have supplied the weekly Advent and Christmas 2020 reflections from their publication, Adore – Advent & Christmas Daily Reflections 2020.