Seventeen seminarians from the Holy Spirit Seminary, Harris Park, all of whom are students for the Diocese of Parramatta, went on an immersion experience in February, becoming acquainted with some of Parramatta’s historical sites. They were accompanied by the new Rector of the Harris Park seminary, Very Reverend Paul Marshall, and the new Vice-Rector, Reverend Dr John Frauenfelder.

Seminarians from the Holy Spirit Seminary with Monsignor John Boyle (back row, third left) during a historical tour of Parramatta. Image: Supplied.

While Parramatta is described as the Cradle of the Nation, it is also the cradle of Catholicism.

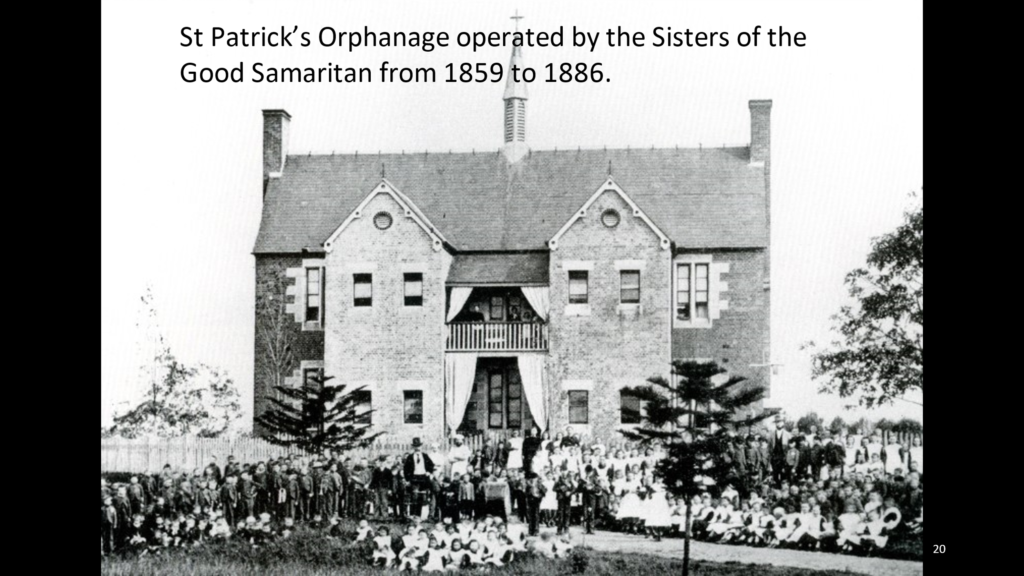

Parramatta claims the oldest convent in Australia, the oldest mortuary chapel, the oldest Catholic cemetery. In Parramatta’s parish church the first profession of a religious took place. The present St Joseph’s Hospital, Auburn, began on the site opposite the present cathedral. The façade of St Patrick’s Orphanage, 500 metres from the cathedral and administered by the Good Samaritan Sisters beginning in 1859, has recently been cleaned and will be repurposed. Next door is the old Female Factory where, from 1840, the Sisters of Charity worked, teaching needlework and sewing, giving some dignity to the women in what was a wretched and godforsaken institution.

A photograph of the St Patrick’s Orphanage, which was operated by the Sisters of the Good Samaritan in Parramatta from 1859 to 1886. Image: Supplied.

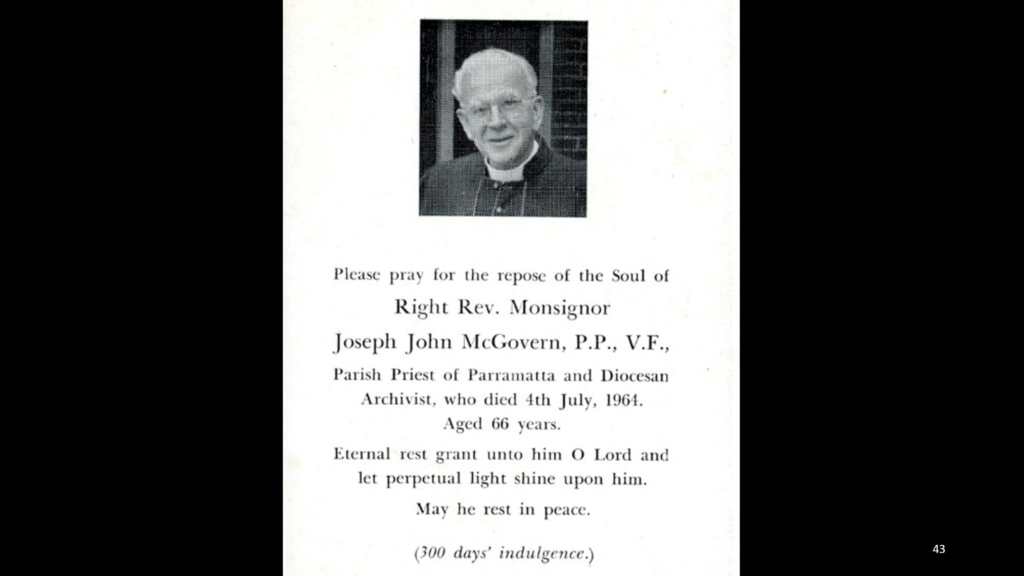

It was in the bell tower of the cathedral, looking at the newly installed ring of bells, that the seminarians heard the oft-repeated story that the original St Patrick’s bells were on the Dunbar, which sank while attempting to enter Port Jackson on a dark and stormy night in August 1857. So powerful was this legend in the oral history of Parramatta parishioners that the ninth Parish Priest of Parramatta, Monsignor Joseph McGovern, paid divers to look for the bells when the Dunbar wreck was “rediscovered” by SCUBA divers in the 1950s. Alas, the legend was disproved when the manifest of the ship’s cargo was produced and nothing resembling a ring of bells appeared anywhere. It is a good story and sits alongside the belief that the first Mass celebrated in Parramatta was celebrated in the loft of the gaol in Hangman’s Green opposite the present cathedral. This error is repeated in the St Patrick’s Parramatta Centenary Magazine, May 1936. (The gaol had been burnt to the ground by persons unknown at the time Father James Dixon said the first Mass in Parramatta in 1803.) To misquote Galadriel in The Lord of the Rings, “History becomes legend and legend becomes myth.” Such legends, however, make telling-the-story interesting!

For the purposes of a pilgrimage to the Parramatta Catholic historical sites, the concept of the magic lantern slide was used. This was a technology fashionable for education and entertainment in the 19th Century but has now morphed into the ubiquitous PowerPoint presentation. The slideshow was downloaded onto the seminarians’ iPhones. When sitting in St John’s Anglican Cathedral in Church Street, it was possible to see what the building looked like in 1803 by going to the downloaded photo. The seminarians were able to access photos of the fire that destroyed St Patrick’s Cathedral on the afternoon of Monday February 19, 1996. They could view a photo of the police interviewing the arsonist.

The seminarians climbed up Rose Hill to Old Government House in Parramatta Park. Here Governor King summoned the Catholics in the colony to hear the proclamation that their prayers for a priest had been answered, and that Father James Dixon, a convict priest, would be granted permission to officially celebrate Mass in May 1803. This site is of historical importance for Catholics because that muster of Roman Catholics, ordered by Governor King, was fulfillment of the wishes of the five Parramatta Catholics, who had petitioned Phillip for a priest way back in 1792.

That document, given to Phillip ten days before he left for England, informs the Governor of “the inconvenience we find in not being indulged with a pastor of our own religion.” It shows that these Catholics were determined to hold on to their religion. “Our present opinion is that nothing could induce us ever to depart from the colony here, unless the idea of going into eternity without the assistance of a Catholic priest.” Four of the petitioners were men. The fifth, Mary Macdonald was a woman. It was dated, Parramatta, November 30, 1792.

Like all the historical buildings in Parramatta, the present Old Government House was closed because of Covid-19, but a guide came in to lead the students on a tour of Governor Lachlan Macquarie’s house, an elegant Palladian style country residence in the English manner. It was begun in 1815 and is maintained in pristine condition by the National Trust of Australia.

Old Government House, Parramatta is where the conditions for the first Masses were pronounced. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Macquarie, who came to the colony in 1810, was not a particularly religious man, but he had a Catholic view of redemption. He believed that once convicts had served their time, they were truly free. Their sin was expunged, and they could re-join society with their past crimes erased. This was the understanding of the layman, Macquarie, but it was not the view of the professional religious man, chaplain and magistrate, Reverend Samuel Marsden, who had been working in the colony some 14 years before Macquarie arrived. It was said of Marsden that “he came to the colony to do good and did very well”.

In 1795, Governor John Hunter made the Church of England chaplains magistrates. Marsden’s role as magistrate at Parramatta attracted criticism amongst his contemporaries because he inflicted harsh punishments on convicts. It was compulsory for Catholics to attend Protestant services. Punishments were directed against the absentees, such as a reduction in the food ration or floggings in the later years. History has remembered Marsden as the ‘Flogging Parson’. He wrote that Catholics “were composed of the lowest class of the Irish nation; who are the most wild, ignorant and savage race that were ever favoured with the light of civilization; men that have been familiar with … every horrid crime from their infancy. Their minds being destitute of every principle of religion and morality render them capable of perpetrating the most nefarious acts in cool blood. As they never appear to reflect upon consequences; but to be … always alive to rebellion and mischief, they are very dangerous members of society. No confidence whatever can be placed in them… [If Catholicism in Australia] were tolerated they would assemble together from every quarter, not so much from a desire of celebrating Mass, as to recite the miseries and injustice of their banishment, the hardships they suffer, and to enflame one another’s minds with some wild scheme of revenge.” [Samuel Marsden, A Few Observations on the Toleration of the Catholic Religion in New South Wales, memorandum, cited in Hughes, p. 188.]

Reading this today would incline us to think that Marsden was not a big fan of ecumenism. He certainly put himself in a conflict-of-interest situation when pronouncing sentence on Catholics who refused to attend his Protestant services. It is an irony that Mamre, Marsden’s country estate (see Genesis 13:18), has recently passed from the hands of the Parramatta Sisters of Mercy to Catholic Care Western Sydney and the Blue Mountains. Marsden would wince if he knew of this turn of events. It could be apocryphal, but people have said that they have heard noises coming from Section One, Row U, Plot 3, St John’s Cemetery, Parramatta. Could it be that Samuel Marsden is turning in his grave?

After a tour of the new Parramatta stadium, the seminarians had a lunch break at the Parramatta Leagues Club. Here was more Catholic history. The Leagues Club is on the present site in O’Connell Street because of a decision taken by the local parish priest in 1958.

It came to pass that an innocuous advertisement was placed by the secretary of the Parramatta Leagues Club, Jack Argent, in the Sydney Morning Herald on 11 February 1958. It announced that the new club was applying for a liquor licence for premises 4-6 Ross Street, Parramatta. Now, 4-6 Ross Street just happens to be opposite the prestigious Our Lady of Mercy College (OLMC) and over the road from St Patrick’s Primary School, a successor of Father Therry’s little school begun in 1820 in Hunter Street, Parramatta.

A photograph taken from No 4-6 Ross Street, Parramatta, across the road to Our Lady of Mercy College, that shows how close the Parramatta Leagues’ Club would have been to OLMC if Monsignor Joseph McGovern had not opposed the granting of a liquor licence to the fledgling Leagues’ Club. Image: Supplied

The Parish Priest, Monsignor Joseph McGovern, sprang into action. Together with the Mother General of the Parramatta Sisters of Mercy, Mother Mary Thecla, a barrister, Mr Bowie, was hired to object to the club’s application for a liquor licence.

The Metropolitan Licencing Court met on St Patrick’s Day and again on the Feast of the Annunciation, at 42 Bridge Street, Sydney. Arguments against the proposed licence included children being run over by inebriated persons as they left the licensed premises, and the fact that patrons would be able to look over the convent wall and into the dormitories of OLMC. On the second day of the hearing continuous rosaries were prayed in the classrooms of St Patrick’s Primary, OLMC and Marist Brothers’ Parramatta. With Our Lady on side, it was inevitable that the Catholics would win. The decision, in favour of the parishioners, was handed down by Licensing Magistrate E J Forrest on the Friday of Easter Week, 1958. The City Engineer, Mr F C Smale, killed off the Ross Street project by recommending that Council reject the proposed development application because, as the Cumberland Argus headlined, ‘Club’s additions clash with religious area’.

This decision meant that the club needed to look for a new location. In October that same year the Secretary of Parramatta Leagues Club Limited, put a second notice in the Sydney Morning Herald advertising that he was applying for a liquor licence for premises “situate at 15 O’Connell Street, Parramatta”. This is where the club now stands at the corner of Eels Place and O’Connell Street, next door to the new stadium. This was truly a win-win situation for both the parish and the club.

Nevertheless, the rumour went around the parish that for the cost and inconvenience of the court action, Monsignor McGovern, although winning the case, had put a hex on the Parramatta Eels, the team that joined the NRL 75 years ago this year, with the effect they would never win a premiership.

Parishioners thought that the curse had worn off in 1976 when Parramatta reached the grand final for the first time. But the Blue and Golds were unsuccessful. Parramatta made it again to the grand final the following season. This match against St George was a draw. A grand final replay was played the following week. Parramatta lost 22 to nil. Obviously, McGovern’s Curse had not been lifted!

A notice calling for prayers for the repose of the soul of former St Patrick’s Parish Priest, Monsignor Joseph McGovern, who died on 4 July 1964. Image: Supplied

In May 1981, Mehmet Ali Agca shot Pope John Paul II in St Peter’s Square. From Rome’s Gemelli hospital, where the Pope was recovering, word spread that Papa Wojtyla had forgiven the would-be assassin. With forgiveness the new buzzword of 1981, and Monsignor McGovern dead for 17 years, the Eels supporters at St Patrick’s Parish felt that the jinx should be lifted. In late September Parramatta won against Newtown, the team they had first played against in 1947. Parramatta had won their first premiership. The football gods were appeased. As a token of appreciation fans burnt down Cumberland Oval. This was the end of an era. The fire that destroyed the oval was a purifying experience and conclusive proof that the curse had died or was at least dormant.

McGovern’s Curse is a case where myth has become legend and legend has become history. In the telling of the story it might be prudent to remember the adage, “never let the truth get in the way of a good story”.

The Chinese may be celebrating the Year of the Tiger, but the Parramatta supporters are convinced 2022, the 75th anniversary of Parramatta joining the NSWRL premiership, is the Year of the Eels.

Monsignor John Boyle is a retired clergy of the Diocese of Parramatta and was Parish Priest of Parramatta and Dean of St Patrick’s Cathedral from 1991 to 2000.