Fifth Sunday of Lent

Readings: Jeremiah 31:31–34; Psalm 129 (130); Hebrews 5:7–9; John 12:20–30

17 March 2024

SPIRITUAL REFLECTION with Katherine Stone MGL

Do you remember what it was like to learn to share? That grudging allowing of someone else to have, or use, a toy that you wanted? Do you remember how excruciating it felt? Like it was killing you on the inside?

Sharing is a glaring example, but I bet if we begin to think about it, we can all come up with countless examples of times where every instinct was screaming at us not to do something in the moment of choosing, perhaps reluctantly and under pressure from others, to let someone else go first, or to forgive, or to tidy up the mess that wasn’t ours. None of these things seem to come naturally—we have to be taught. And it seems, in my experience, to be the stuff of “adulting”.

Ironically, while we spend a lot of our childhood dreaming of being grown up and getting to do what we want, we discover as adults that all of the lessons that we have imbibed about selflessness are actually lessons in the logic of love. We then spend the rest of our lives choosing to do things we don’t want to do as conscious acts of love for others.

Jesus consistently takes these lessons to a new level. From the beginning of his public ministry, we hear him speak of loving not just friends and family, but strangers and even enemies. Ultimately, he says, the greatest love is seen in willingness to die for another. Then he goes on to demonstrate this “greatest love” by dying for us. And, as St Paul points out, it is one thing to die for someone good or innocent or whom you are very close to, but what makes Jesus’ love for us extraordinary was his choice to die for us before we have proven ourselves to be any of those things. In him, we consistently see the compassionate heart of God.

This kind of loving is one that we aren’t humanly capable of without help. Just like our parents and teachers had to teach us to share and forgive, and speak the truth, so God has taught us how to love. And it looks like the Cross.

Jesus is very clear that following him means taking the road to the cross. This is not because he is glorifying suffering in itself, but because ultimately, to truly love means to die to ourselves. God has done us the honour of inviting us to become like him. God is love. Therefore, we, too, are called to become love. Hence the Cross.

Thankfully, we don’t have to do it alone. That’s what the first reading is referring to when God says that he will write his Law on our hearts. The Holy Spirit, given to us at our Baptism, is the love of God dwelling within us. As we learn more and more to listen to the Spirit in our hearts, we will find ourselves choosing, again and again, the way of suffering love.

Perhaps the way to recognise the prompting of the Spirit may be, first of all, in hindsight. Looking back over a day, we can recall those moments where we got in touch with the child inside, where we can recognise the excruciating inner fight against something we knew that we “probably should” do. Then, with the help of the Spirit, we can “be the adult” to ourselves, listening to our own arguments and pain, but ultimately assessing which choice was the way to love and life, and resolving, with God’s help, to choose it next time.

REFLECTING ON THE READINGS THROUGH ART with Mgr Graham Schmitzer

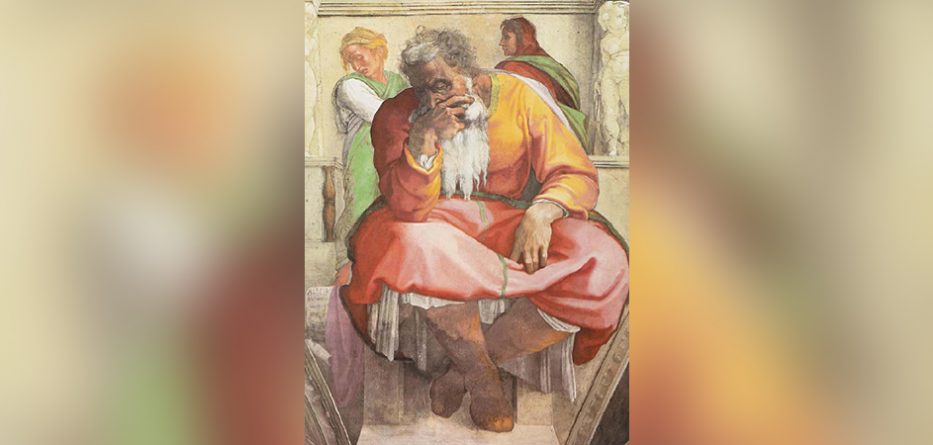

The Prophet Jeremiah – Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni (1475–1564)

“The Prophet Jeremiah” (c. 1510–1512), Fresco, 390cm × 380cm. Sistine Chapel, Vatican Palace, Vatican City. Public Domain.

“See, the days are coming.” The Church puts on her own lips the words of the prophet Jeremiah. Holy Week begins next Sunday—the days of celebration when, through the Liturgy, God enters once more into the history of his people. It is the year of Our Lord 2024, the year of our salvation. Every year is the year of our salvation, for we worship a timeless God. It is as if there were no real difference between the year 33 and the year 2024. Christ’s sacrifice on Calvary for us, and the acceptance of that sacrifice by his Father in raising his Son from death, will be made present every year until the end of time.

Christ’s sacrifice fulfils the Covenants of old. We read of them on Sundays One, Two, and Three. It was God of course, who took the initiative, so close did he wish to draw to his people. But, says Jeremiah, God’s people broke off their marriage with him, and they did it again and again. Today’s reading was written at the beginning of the sixth century before Christ—the beloved city of Jerusalem had fallen, and her inhabitants were to be exiled to Babylon. The northern kingdom of Judah had already collapsed. Despair and fear gripped the people who were now empty of hope. Had their promise making God deserted them? Had he had enough of their repeated infidelities?

Jeremiah, perhaps best of all the prophets, knew how God felt. Jeremiah was persecuted and almost killed for attempting to reform the nation. He had faithfully reported God’s anguished appeal to Israel: “I remember your faithful love, the affection of your bridal days, when you followed me through the desert…. Israel was sacred to Yahweh, the first-fruits of his harvest” (Jr 2:1–3). For this, Jeremiah was hated. Yet he could not resist God’s call. “You have seduced me, Yahweh, and I have let myself be seduced; you have overpowered me; you were the stronger” (Jr 20:7). Like so many prophets, Jeremiah acted out in his life the message he was declaring. Like God himself, he could not give up on his people. His very sufferings purified his soul of everything unworthy, and made it open to God.

God had never given up. He would say through the prophet Hosea: “My people are bent on disregarding me.… [but] I will not give reign to my fierce anger … for I am God, not man, the Holy One in your midst, and have no wish to destroy” (Ho 11:7–9).

Jeremiah sees into the future. “The days are coming” when God will pour new life into his people. The kingdoms of the north and the south would be reunited, the people’s coming exile in Babylon would come to an end, the Temple (as we heard last Sunday) would be rebuilt. And God would be prepared to make a New Covenant, this time forever. It would be inscribed not on tablets of stone, but would be incised into the people’s hearts. The pierced Heart of Jesus would be the guarantee of God’s part of the bargain. Without knowing it, then, the centurion on Calvary would be carrying out the divine plan.

The New Covenant would be carved into the very Heart of Christ. All who come to this Heart “in the coming days” will find that their sins will never again be called to mind (Jr 31:34).

There is a wonderful story told of St Margaret Mary Alacoque to whom Our Lord revealed his Sacred Heart. She confided her visions to her confessor, the Jesuit, Claude de la Colombière. To test her genuineness, he requested her to question Our Lord about the contents of his last Confession. At her next visit, St Claude asked if she had carried out his wish. “Yes,” said Margaret Mary “he said he’s forgotten what you said in your last Confession.”

Jeremiah would have been amazed if he had foreseen what the new Covenant involved, that God himself would be the sacrifice, the “trustful lamb being led to the slaughter-house” (Jr 11:19). The letter to the Hebrews, which forms today’s second reading, surely tugs at our heart as the writer highlights Jesus’ humanness. A Man in the prime of his life, about to be betrayed by both the the religious authorities of the time and the nation, crying to God “aloud and in silent tears” (Heb 5:7). Like Jeremiah before him, he learned obedience through suffering. “Obedience” comes from the Latin ob-audire, to listen closely. We cannot know of God’s love until we are prepared to spend time listening to him telling us of his love. His obedient suffering, the author is at pains to impress on us, places him in solidarity with all who have unjustly suffered throughout time. Not only is today’s psalm (50) on our lips, it is also on Christ’s lips. When we pray the psalms, we should remember that, as an observant Jew, Jesus prayed these prayers all his life, taught to him obviously by his parents. It was these prayers that shaped his trust in his Father.

The request in today’s Gospel: “We should like to see Jesus,” is ours, too. And we shall see him in “the coming days” as the sacred liturgy re-presents the mystery of our salvation. The Covenant is not “of old”. It is of today, and we have the chance to “sign up” again, especially in the renewal of our marriage vows with God on Holy Saturday night, and again on Easter Sunday. God’s Covenant is never just a contract; it is an eternal invitation, beautifully expressed in poetry by George Herbert (1593–1633) in the poem, Love:

Love bade me welcome; yet my soul drew back,

Guilty of dust and sin.

But quick-ey’d Love, observing me grow slack

From my first entrance in,

Drew nearer to me, sweetly questioning,

If I lacked anything;

“A guest,” I answered “Worthy to be here.”

Love said, “You shall be he.”

“I, the unkind, ungrateful? Ah, my dear

I cannot look on Thee.”

Love took my hand, and smiling did reply

“Who made the eyes but I?”

“Truth, Lord, but I have marr’d them;

let my shame

Go where it doth deserve.”

“And know you not,” says Love “Who bore the blame?”

“My dear, then I will serve.”

“You must sit down,” says Love

“And taste my meat.”

So I did sit and eat.

Michelangelo (di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni) holds the distinction of being the first Western artist to have his biography published while he was still alive. Remarkably, not just one, but three biographies were published during his lifetime. His fellow artists and contemporaries frequently marvelled at Michelangelo’s terribità, which refers to his remarkable talent for evoking a sense of awe and reverence in those who viewed his artwork. Despite not identifying himself primarily as a painter, Michelangelo left an indelible mark on the history of Western art by creating two incredibly influential frescoes. These masterpieces are the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel and The Last Judgement on its altar wall. Michelangelo’s talent and fame were evident from an early age. By the time he was 30, he had already sculpted two of his most renowned works, The Pietà and The David. Later in life, at the age of 71, he took on the role of the architect for the construction of the new St Peter’s Basilica, succeeding Antonio da Sangallo the Younger in this important endeavour.

Initially, Michelangelo was tasked with painting the Twelve Apostles on the triangular pendentives that supported the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. Additionally, he was assigned to decorate the central part of the ceiling with ornamentation. However, Michelangelo managed to convince Pope Julius II to grant him artistic freedom and allow him to express his creativity without constraints. The result was a composition stretching over 500 square metres of ceiling, containing 300 figures. In the middle of the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, there are nine scenes depicting important events from the book of Genesis. Surrounding these scenes, on the pendentives that support the ceiling, Michelangelo painted twelve figures. These figures consist of seven prophets from Israel who foretold the coming of Christ, as well as five sibyls, who were prophetic women from the classical world. These figures serve to highlight the connection between the Old Testament prophecies and the fulfilment of those prophecies in the life of Christ.

We are looking at the prophet Jeremiah, the first fresco on the left from the side of the high altar. In Michelangelo’s depiction of Jeremiah on the Sistine Chapel ceiling, the prophet is portrayed as deeply immersed in troubled thoughts. He appears to be burdened by the weight of his prophetic messages, particularly the foretelling of the destruction of Jerusalem. Jeremiah is shown leaning forward, with his head resting on his hand and his elbows on his spread knees.

Some critics have interpreted this figure as a possible self-portrait by Michelangelo. They suggest that the artist may have used Jeremiah as a way to express his own feelings of remorse and guilt, possibly reflecting on his own sins. Another interpretation is that Michelangelo, in depicting Jeremiah in this manner, is expressing his frustration and unhappiness with being compelled by Pope Julius to paint instead of pursuing his preferred medium of sculpture.

Katherine Stone MGL is a Missionaries of God’s Love (MGL) sister living in Varroville, NSW. Originally hailing from Tasmania, she joined the MGL Sisters in 2005. Since then, she has lived in Canberra, Melbourne and Sydney, studied theology and spiritual direction, and has done a term as formator. These days, her main ministries are spiritual direction, talks and teaching, and retreat giving. She is also the MGL sisters’ vocations director. Her passion is Jesus—as may be apparent from her ministry, she loves talking about him and to him, and hearing others share their own experiences of him.

Monsignor Graham Schmitzer is the retired parish priest of Immaculate Conception Parish in Unanderra, NSW. He was ordained in 1969 and has served in many parishes in the Diocese of Wollongong. He was also chancellor and secretary to Bishop William Murray for 13 years. He grew up in Port Macquarie and was educated by the Sisters of St Joseph of Lochinvar. For two years he worked for the Department of Attorney General and Justice before entering St Columba’s College, Springwood, in 1962. Mgr Graham loves travelling and has visited many of the major art galleries in Europe.

With thanks to the Diocese of Wollongong, who have supplied this reflection from their publication, Pietà – Lenten Program 2024. Reproduced with permission.