Homily for the 4th Sunday of Lent┬Ā

29 March 2025

Joshua 5:9-12; Psalm 34; 2 Corinthians 5:17-21; Luke 15:1-3, 11-32

Listen at https://soundcloud.com/frank-brennan-6/homily-30-3-25

TodayŌĆÖs gospel presents us with two segments from Chapter 15 of LukeŌĆÖs gospel. ┬ĀThe first segment is just three verses which introduce the theme of all that is to follow. ŌĆśTax collectors and sinners were all drawing near to listen to Jesus,but the Pharisees and scribes began to complain, saying, ŌĆ£This man welcomes sinners and eats with them.ŌĆØŌĆÖ ┬ĀThese religious authorities and religiously righteous persons were distressed that Jesus was attracting tax collectors and sinners. ┬ĀHe was just not attracting the right sort of religious people. ŌĆśHe was not attracting our sort of people!ŌĆÖ In fact, he was attracting the wrong sort of non-religious people. ┬ĀSo Jesus then tells three parables to the snooty, righteous interrogators who were complaining about the company Jesus was attracting and keeping.

In todayŌĆÖs gospel, weŌĆÖre not given the first two parables. ┬ĀThe first parable is addressed directly to those who are complaining. ┬ĀJesus asks them to imagine having 100 sheep. ┬ĀThen imagine losing one. ┬ĀWhat would you do? ┬ĀYouŌĆÖd do all you could to find it. ┬ĀWhen you did find it, you wouldnŌĆÖtwhinge and complain as you are doing now. ┬ĀYou wouldrejoice. ┬ĀThe shepherd finding the lost sheep ŌĆśgoes to his house and gathers his friends and neighbours. He says to them: ŌĆ£Rejoice with me! I have found my lost sheep!ŌĆØŌĆÖ

The second parable is about a woman with 10 valuable coins. ┬ĀShe loses one and does all she can to find it. ┬ĀWhen she does find it, she rejoices. ┬ĀShe does not complain. ┬ĀŌĆśWhen she finds it, she gathers her women friends and neighbours. She says, ŌĆśRejoice with me! I have found my lost coin!ŌĆÖ So too with Jesus. ┬ĀWhen he finds a tax collector or sinner who was lost, he says to one and all, including the self-righteous ones: ŌĆśRejoice with me. ┬ĀCome to the table. ┬ĀShare the feast. ┬ĀThe one who was lost has been found.ŌĆÖ ┬ĀThatŌĆÖs his message to us, especially during Lent.

The second segment of todayŌĆÖs gospel is the all too familiar parable of the prodigal son. ThereŌĆÖs a rich father with two sons. ┬ĀOne son is a goody goody who stays home and does the right thing. ┬ĀThe other is a vagabond who takes off with his share of the inheritance, wasting it all on wine, women and song. ┬ĀHe falls on hard times. ┬ĀHe then wakes up to himself, realising that his fatherŌĆÖs servants would be doing it better than he is, eking out an existence as a hired farmhand. ┬ĀHe decides to return home seeking forgiveness. ┬ĀHe never gets to deliver his prepared speech. ┬ĀThe father spotting the lost son far off, rushes to him, and orders that he be attired with robes, ring and sandals. ┬ĀThe father orders a feast proclaiming: ŌĆśThis is my son! He was dead and has come back to life! He was lost and has been found!ŌĆÖ ┬Ā

The goody goody son sees all this. ┬ĀHe doesnŌĆÖt like what he sees. ┬ĀHe is like those Pharisees and scribes Jesus is addressing. ┬ĀRather than rejoicing at the return of his brotherwho was lost, he complains. ┬ĀHe says itŌĆÖs just not fair. ┬ĀThe father says to him: ŌĆśMy son, you are here with me always;everything I have is yours. ┬ĀBut now we must celebrate and rejoice, because your brother was dead and has come to life again; he was lost and has been found.ŌĆÖ

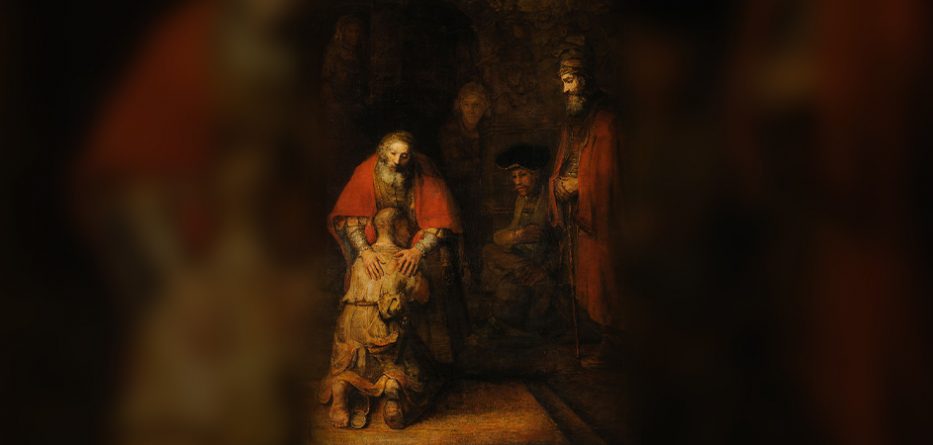

The Return of the Prodigal Son by Rembrandt great painting in a Hermitage at St PeterŌĆÖs, pictured by Fr Frank Brennan SJ. Image: supplied

In December 2008, I was privileged to visit the Hermitage in St Petersburg. ┬ĀIt was so cold that there were hardly any tourists. ┬ĀIt was as if my niece and I had the place to ourselves. ┬ĀIt meant that we could spend time uninterrupted pondering RembrandtŌĆÖs great painting of The Return of the Prodigal Son.┬ĀLater on our tour of the gallery, I slipped back and saw a young Asian mother with her two little children in front of the painting. ┬ĀShe was obviously explaining the painting to the kids. ┬ĀI was moved that such a painting could speak to people of all cultures and all ages. ┬Ā

It was only later that I learnt that earlier the young 29 year oldRembrandt had painted The Prodigal Son in the Brothelportraying two people who were identified as him and his wife Saskia. As a young couple they had a happy marriage. ┬ĀRembrandt was a highly successful artist. ┬ĀThey were living the good life, the carefree life, the style of life which was frowned upon by many religious folk in Calvinist Amsterdam. ┬ĀIt was 32 years later that Rembrandt painted The Return of the Prodigal Son. ┬ĀSaskia and all their four children had died. Rembrandt was on his own. New artists like Vermeer were taking the spotlight from Rembrandt. ┬ĀHe was just two years from death. ┬ĀRembrandt saw something of himself in all three main characters in this later painting ŌĆō the compassionate father, the righteous son, and the son seeking forgiveness. ┬Ā

ThatŌĆÖs what makes the painting so warm and inviting. ┬ĀJust as there is something of the artist in all the main characters, there is something of each of us in all the main characters. ┬ĀWe all have the capacity to be self-righteous and judgmental. ┬ĀWe all have the capacity to seek forgiveness. ┬ĀWe all have the capacity to show compassion. ┬ĀThere have been times when each of us has been self-righteous and judgmental. There have been times, and during Lent there is every opportunity, to seek forgiveness. ┬ĀThere have been times when we have shown compassion and when we have received compassion. ┬ĀThe spiritual writer Henri Nouwen writes in his book The Return of the Prodigal Son: ŌĆśThough I am both the younger son and the elder son, I am not to remain them, but called to become the Father.ŌĆÖ┬Ā

Looking closely at the hands of the father in the painting,Nouwen reflects:

ŌĆśThe fatherŌĆÖs left hand touching the sonŌĆÖs shoulder is strong and muscular.┬Ā The fingers are spread out and cover a large part of the prodigal sonŌĆÖs shoulder and back.┬Ā I can see a certain pressure, especially in the thumb.┬Ā That hand seems not only to touch, but, with its strength, also to hold.┬Ā Even though there is a gentleness in the way the fatherŌĆÖs left hand touches his son, it is not without a firm grip.┬Ā

ŌĆśHow different is the fatherŌĆÖs right hand!┬Ā This hand does not hold or grasp.┬Ā It is refined, soft, and very tender.┬Ā The fingers are close to each other and they have an elegant quality.┬Ā It lies gently upon the sonŌĆÖs shoulder.┬Ā It wants to caress, to stroke, and to offer consolation and comfort.┬Ā It is a mother’s handŌĆÖ.

ŌĆśAs soon as I recognized the difference between the two hands of the father, a new world of meaning opened upfor me.┬Ā The Father is not simply a great patriarch.┬Ā He is mother as well as father.┬Ā He touches the son with a masculine hand and a feminine hand.┬Ā He holds, and she caresses.┬Ā He confirms and she consoles.┬Ā He is , indeed, God, in whom both manhood and womanhood, fatherhood and motherhood, are fully present.ŌĆÖ

I donŌĆÖt know what that young mother told her kids at the Hermitage back in 2008, but I do hope they came away, as did I, touched that we are offered healing, forgiveness and fulness of life with both hands, whether we be the righteous child, the disgraced child or the forgiving parent. ┬ĀAll of us are invited to the table of the banquet. ┬Ā

Taste and see the goodness of the Lord.

We will glory in the Lord;

let the humble hear and rejoice.

Proclaim with us the greatness of the Lord;

let us exalt the name of God together.

We sought the Lord, who answered us

and delivered us out of all our terror.

Look upon God and be radiant,

and let not your faces be ashamed.

We called in our affliction and the Lord heard us

and saved us from all our troubles.

The angel of the Lord encompasses those who fear God

and will deliver them.

Taste and see the goodness of the Lord.

[1] Henri Nouwen, The Return of the Prodigal Son: A Story of Homecoming, London : Darton, Longman & Todd, 1994, 98-9.

[2] During the week, I delivered an address in the parish on Catholic Social Teaching in the Public Square ŌĆō reflections on 50 years as a Jesuit.┬Ā It is available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RrYg2Kh78UY

Fr Frank Brennan SJ is serving as part of a Jesuit team of priests working within a new configuration of the Toowong, St Lucia and Indooroopilly parishes in the Archdiocese of Brisbane. Frank Brennan SJ is Adjunct Professor of the Thomas More Law School at ACU and┬Āis a former CEO of Catholic Social Services Australia (CSSA). Fr FrankŌĆÖs latest book is┬ĀAn Indigenous Voice to Parliament: Considering a Constitutional Bridge, Garratt Publishing, 2023 and┬Āhis┬Ānew book┬Āis ŌĆśLessons from┬ĀOur Failure to Build a Constitutional Bridge in the 2023 ReferendumŌĆÖ (Connor Court, 2024).