Homily for the 6th Sunday in Ordinary Time

Leviticus 13:1-2, 44-66; Psalm 32; 1 Corinthians 10:31-11:1; Mark 1:40-45

11th February 2024

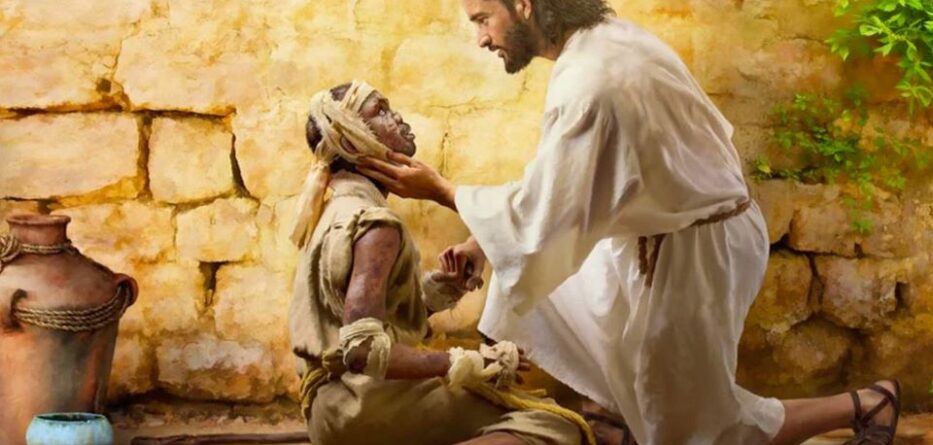

We are getting used to Mark’s style. In today’s gospel describing Jesus’ cure of the leper, we are once again told that the leprosy left the man AT ONCE and that Jesus IMMEDIATELY sent the man away. We are still in Chapter 1 of the gospel and once again, those in the know about Jesus’ identity and power are told to keep it all a secret; and now that the word has got out, ‘Jesus could no longer go openly into any town, but had to stay outside where nobody lived.’ Jesus is a man of action. He acts resolutely and promptly, and expects us to do the same.

Jesus stretches out his hand and touches the leper. This is a truly shocking action. It was one thing to cure a leper as Elijah did with Naaman in the second book of Kings. But it was an altogether different thing to actually touch the leper. Jesus reaches out to the excluded one. And Jesus suffers the fate of one who is so inclusive. He is excluded by the religious authorities and by the mob.

Listen at https://soundcloud.com/frank-brennan-6/homily-11224

Pope Francis with his synod process and with the approval of blessings for same-sex couples has been boldly reaching out to the excluded, proclaiming a church that needs to be more inclusive. Meeting a delegation from the US University of Notre Dame recently, Francis said, ‘We cannot stay within the walls or boundaries of our institutions, but must strive to go out to the peripheries and meet and serve Christ in our neighbour.’

In 2012, Fr Tomas Halik, psychotherapist, university chaplain, and Rector of the Church of the Holy Saviour in Prague, the capital of the Czech republic, published Night of the Confessor: Christian Faith in an Age of Uncertainty. Back then, he engaged in a speaking tour here in Australia. I was privileged to conduct a couple of public conversations with him.

Halik does not write for those certain in their faith or for those certain in their antipathy or indifference to faith. He reaches out to those who find kernels of truth and seeds of doubt in both. He imagines the reader who is ‘prepared to suspend for the time being the moment of agreement or disagreement’. He delights in appealing both to believers and non-believers perplexed and tantalised by the mystery and paradox of life. In Night of the Confessor, he recalls Oskar Pfister’s response to Sigmund Freud wondering if a Christian could be tolerant of atheism: ‘When I reflect that you are much better and deeper than your disbelief, and that I am much worse and more superficial than my faith, I conclude that the abyss between us cannot yawn so grimly.’

In 2014, Halik won the prestigious and lucrative Templeton prize which ‘honours individuals whose exemplary achievements advance Sir John Templeton’s philanthropic vision: harnessing the power of the sciences to explore the deepest questions of the universe and humankind’s place and purpose within it.’

In 2016 he was awarded an honorary doctorate by Oxford University. The citation noted: ‘As physician, pastor and writer he gave thoughtful attention equally to his own flock and to those wandering outside it; and thus his ideas have spread far and wide.’ It also noted that he dedicated his Templeton prize ‘to those priests who perished in prisons, mines and concentration camps. He himself endured long privations because of his active part in what was known as the Underground Church: for many years he was banned from university teaching and from travel abroad.’

This month he is publishing a new book: The Afternoon of Christianity: The Courage to Change. In the coming week, I will once again join him in public conversations in Sydney and Melbourne.

Explaining the purpose of this new book, he says: ‘If Christianity is to overcome the crisis of its many previous manifestations and become an inspiring response to the challenges of this time of great civilisational change, it must boldly transcend its previous mental and institutional boundaries. The time has come for Christianity to transcend itself.’ He repeats many times his conviction that ‘a distinctive feature of postconciliar Christianity will be an increasing ecumenical openness.’

He says: ‘there is a need for dialogue between the different psychological types of faith within Christianity: between faith as a way and faith as a certainty, between the Church as a community of pilgrims and the Church as a home, between the Church as a community of memory and narrative and the Church as a field hospital.’ He asks: ‘Will the church of the future be able to be a common home for these different aspects and forms of religiosity?’

Attentive particularly to the young inquiring minds he encounters at university, he insists that ‘The Church needs to create spiritual centres, places not only of adoration and contemplation, but also of encounter and conversation, where experiences of faith can be shared.’

He has this compelling image: ‘While the traditional institutional forms of religion often resemble drying riverbeds, interest in spirituality of all kinds is a surging current undermining old banks and carving out new channels.’

He sees the church as an expansive all-inclusive community of listening and understanding. He recounts a Czech legend:

‘[T]he builder of one of the Gothic churches in Prague ordered the wooden scaffolding to be set alight after the construction was finished. When the fire ignited and the scaffolding tumbled thunderously to the ground, the builder panicked and committed suicide, thinking that his building had collapsed. It seems to me that many Christians who are in a panic at this time of change are succumbing to a similar error. What is collapsing may be only wooden scaffolding; when it burns down, the church building will certainly be scorched by fire, but the essentials, which have long been hidden, are yet to be revealed.’

Since he won the Templeton prize, Halik has been quite a globetrotter being able to converse with some of the world’s leading theologians in places like Oxford, Harvard, the University of Notre Dame and Boston College. He puts out this challenge to those of us in long-established parishes:

‘When, in much of the world, the network of local parishes collapses like the scaffolding of the church in the legend I quoted …, spiritual strength will have to be derived from centres of communal prayer and meditation, where celebration takes place, as well as reflection and the sharing of faith experiences.’

We commence our Lenten worship and practices this Wednesday. As part of our Lenten discipline, let’s commit ourselves to reaching out and touching the excluded, the different – AT ONCE. Let’s make a time and place for listening, understanding and conversation with all persons of good will – IMMEDIATELY.

I turn to you, Lord, in time of trouble, and you fill me with the joy of salvation.

Happy the person whose offence is forgiven,

whose sin is remitted.

O happy the one to whom the Lord

imputes no guilt,

in whose spirit is no guile.

I turn to you, Lord, in time of trouble, and you fill me with the joy of salvation.

From the start of 2024, Fr Frank Brennan SJ will serve as part of a Jesuit team of priests working within a new configuration of the Toowong, St Lucia and Indooroopilly parishes in Brisbane Archdiocese. Frank Brennan SJ AO is Adjunct Professor and Distinguished Fellow of the PM Glynn Institute, Australian Catholic University. He is a former CEO of Catholic Social Services Australia (CSSA) and his latest book is An Indigenous Voice to Parliament: Considering a Constitutional Bridge, Garratt Publishing, 2023.