Homily for the 16th Sunday in Ordinary Time

23 July 2023

Readings: Wisdom 12:13,16-19; Psalm 85; Romans 8:26-27; Matthew 13:24-43

In today’s gospel, Jesus tells another parable: ‘The kingdom of heaven may be compared to a farmer who sowed good seed in their field. While everybody was asleep their enemy came, sowed darnel all among the wheat, and made off. When the new wheat sprouted and ripened, the darnel appeared as well.’ The servants think the only thing to do is to remove the darnel immediately. The wise farmer instructs them: ‘Let the wheat and darnel both grow till the harvest; and at harvest time I shall say to the reapers: First collect the darnel and tie it in bundles to be burnt, then gather the wheat into my barn.’ And so it is in life whenever we are confronted with the big issues.

Everyone is talking about Christopher Nolan’s new blockbuster movie Oppenheimer. There was not a spare seat in the theatre on Friday night when I went. The film is a three hour search into the heart and soul of J. Robert Oppenheimer, the physicist known as the father of the atomic bomb. His parents were German Jews. A migrant with every opportunity then to study physics in the US and Europe, Oppenheimer was convinced that it was essential that the Americans discover the bomb before the Nazis did. His motivation was clear. He was intent on planting only good wheat. Chosen to head the Manhattan project at Los Alamos, he led a team who successfully detonated the Trinity test bomb in the desert on 16 July 1945. But by then, they knew that the Germans had no chance of producing such a bomb. Oppenheimer and Einstein had discussed the enormity of the consequences of new scientific discoveries like splitting the atom. Some years after the test and the subsequent dropping of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Oppenheimer recalled the moment of that first detonation in the desert as the scientists and US military personnel looked on from a safe distance: ‘We knew the world would not be the same. A few people laughed, a few people cried, most people were silent.’ He called to mind a verse from the Bhagavad Gita: ‘Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.’ No matter what his original motives, Oppenheimer knew he had planted a field of wheat and darnel.

LISTEN: https://soundcloud.com/frank-brennan-6/homily-23723

The US objective in dropping the bombs on Japanese cities was to bring the war to an end without the need to stage a bloody invasion of a nation whose leadership was implacably opposed to unconditional surrender. President Truman’s military advice was that a land invasion of Japan would cost at a minimum a quarter of a million American casualties. Without the use of the bomb, war was expected to last another year. A million Allied troops were being moved into place for the invasion of Japan. After the war, Truman observed, ‘It occurred to me that a quarter of a million of the flower of our young manhood were worth a couple of Japanese cities, and I still think they were and are.’ Having authorised the use of the atomic bomb, Truman told his wife three weeks before Hiroshima that ‘we’ll end the war a year sooner now’.

On the day he authorised the military to go ahead with preparations to use the bomb on Japanese cities, Truman wrote in his diary: ‘I have told the Secretary of War, Mr Stimson, to use it so that military objectives and soldiers and sailors are the target and not women and children. …. The target will be a purely military one and we will issue a warning statement asking the Japs to surrender and saves lives.’ Truman’s rationalisation was completely false, and he knew it was. Truman was harvesting a field of darnel as well as wheat. All this was far removed from Oppenheimer’s original motivation, wanting to beat the Nazis to the goal of devising a bomb so terrible that if held in the right hands might put an end to escalating war and conflict.

After the dropping of the second bomb, the Japanese Emperor decided to ‘bear the unbearable’ and surrender. Five days after the two bombings, the Japanese accepted the terms of the Potsdam Declaration and surrendered. Three years later, at a meeting of the National Security Council to discuss the custody of the atomic bomb, Truman insisting that it remain under civilian control, said: ‘I don’t think we ought to use this thing unless we absolutely have to. It is a terrible thing to order the use of something that is so terribly destructive, destructive beyond anything we have ever had. You have got to understand that this isn’t a military weapon. It is used to wipe out women and children and unarmed people, and not for military uses. So we have got to treat this differently from rifles and cannon and ordinary things like that.’

I daresay most Australians still think President Truman did right in authorising the dropping of the atomic bombs on Japanese cities, regardless of whether such bombs are classed ordinarily as military weapons or not, and regardless of the fact that the dropping of those bombs entailed a direct attack on the innocent with the intent to do them injury. They thought, and still do, that the obliteration of the civilian populations of Hiroshima and Nagasaki was morally excused if not justified because this, and only this, helped to end the war, without the need for hundreds of thousands of Allied Forces having to face annihilation invading Japan with its citizenry blindingly committed to the Emperor’s honour.

In 1965, the Second Vatican Council solemnly declared: ‘Any act of war aimed indiscriminately at the destruction of entire cities of extensive areas along with their population is a crime against God and man himself. It merits unequivocal and unhesitating condemnation.’1 There is no other church moral teaching which has been so solemnly declared. Many democratic leaders if placed in Truman’s shoes would in good conscience, and with a very heavy heart pleading for God’s mercy, or at least seeking the approval of their people, invoke an exception and do exactly the same again, no matter what any church leader said.

In the movie, there is a scene when Oppenheimer meets with President Truman in the Oval Office two months after the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings. Oppenheimer says, ‘I have blood on my hands.’ Truman rebuts him, saying, ‘You built it, but I dropped it’. Truman later said to others: ‘Blood on his hands, dammit, he hasn’t half as much blood on his hands as I have. You just don’t go around bellyaching about it.’ Describing Oppenheimer as ‘a crybaby scientist’, Truman told his secretary of state: ‘I don’t want to see that son of a b**ch in this office ever again.’ The two never met again.

Oppenheimer went on to express grave moral qualms about the development of the H-bomb. His critics thought him unAmerican. His enemies conspired to have his security clearance withdrawn in 1954. Oppenheimer always regarded himself as a loyal patriot, but in the McCarthy era, he was condemned. According to Einstein, ‘The trouble with Oppenheimer is that he loves a woman who doesn’t love him—the United States government.’ It was not until John F Kennedy became president that Oppenheimer’s reputation was rehabilitated.

Before and after the successful detonation of the Trinity bomb, Oppenheimer knew that he had sewn a field of wheat and darnel, a field which could be controlled by others whose motivations he would never control. His moral qualms were real; and they were deliberately misconstrued as the manufacture of a traitorous mind.

He was not a believer, but if he were, he could have prayed as we do, whether Jews or Christians:

Lord, you are good and forgiving.

O Lord, you are good and forgiving,

full of love to all who call.

Give heed, O Lord, to my prayer

and attend to the sound of my voice.

Lord, you are good and forgiving.

All the nations shall come to adore you

and glorify your name, O Lord:

for you are great and do marvellous deeds,

you who alone are God.

Lord, you are good and forgiving.

But you, God of mercy and compassion,

slow to anger, O Lord,

abounding in love and truth,

turn and take pity on me.

Lord, you are good and forgiving.2

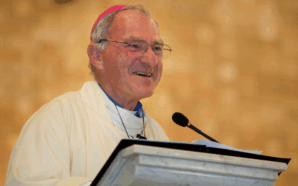

Fr Frank Brennan SJ is the Rector of Newman College, Melbourne, and the former CEO of Catholic Social Services Australia (CSSA).

1 Gaudium et Spes, #80, available at https://www.vatican.va/archive/hist_councils/ii_vatican_council/documents/vat-ii_const_19651207_gaudium-et-spes_en.html

2 Meanwhile the third edition of my book An Indigenous Voice to Parliament is now available at https://www.garrattpublishing.com.au/product/9781922484826/. My latest talk on the Voice is available at https://soundcloud.com/frank-brennan-6/frenchs-forest-catholic-parish