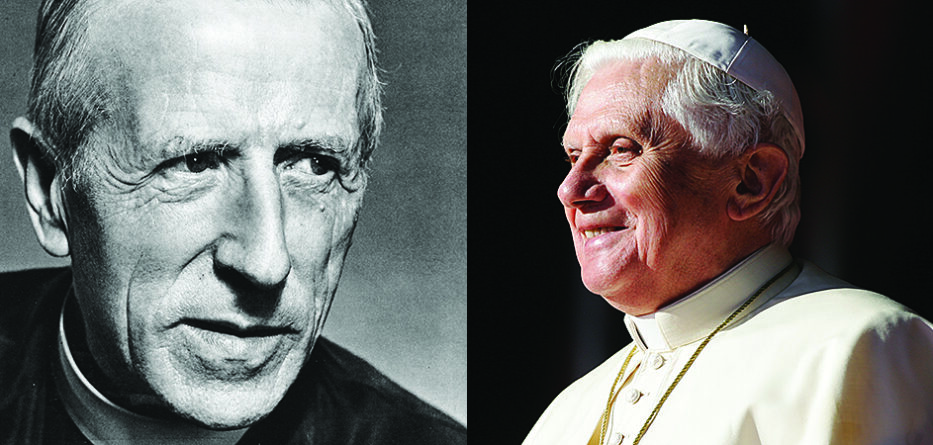

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (1881-1955), a Jesuit, anthropologist and prominent spiritual figure, experienced the powerful tensions of a complex twentieth century marked by wars, ideological controversies and major discoveries.[1] Among Teilhard’s readers was Joseph Ratzinger. Teilhard’s name appears six times in Introduction to Christianity, a 1968 work by Ratzinger that has already become a classic. In fact, the Jesuit paleontologist’s name is one of the most frequently mentioned in this book, which continues to fascinate for its freshness and novelty within the Christian tradition. Like it or not, Ratzinger admired Teilhard. From his earliest writings he regarded the Jesuit as a key author for Christian aggiornamento in the modern world. In the words of the theologian-turned-pope we can accept that the “synthesis” proposed by Teilhard remains “faithful to Pauline Christology, whose profound thought is clearly perceived and restored to a new intelligibility.”[2]

It is through Ratzinger’s writings that we can see how the reception of the Teilhardian vision was also present in Vatican II, albeit somewhat marginally. As a leading figure at the Council, Ratzinger was of the view that there was a certain evidence of Teilhard’s thought in the draft of the famous pastoral constitution Gaudium et Spes, especially with regard to “the Teilhardian theme” that “Christianity means greater progress.”[3]

In inaugurating the Second Vatican Council, John XXIII well summarized its pastoral objective: to return to the sources and adapt the Church’s response to the modern world. It was, in essence, to “bring the modern world into contact with the life-giving and perennial energies of the Gospel.” As Supreme Pontiff, Benedict XVI quoted these words of his predecessor, St. John XXIII, revealing his interpretation of the Council as a constructive dialogue between the Church, history and the “world of culture” in general. Having a “renewed awareness of the Catholic tradition,” Vatican II sought to take “seriously […] the criticisms underlying the currents that have characterized modernity,” in order to discern them, transfigure them and engage in dialogue with them. In doing so, “the Church accepted and refashioned the best of the emphases of modernity,” while laying “the foundation for an authentic Catholic renewal and a new civilization, the ‘civilization of love’.”[4]

We therefore understand that the theologian pope did not affirm the continuity of Christian Tradition in a reactionary or fundamentalist way. It is true that for him continuity through traditio was important, indeed fundamental, as was the unity of the Church. But the so-called “hermeneutics of continuity” is never involved without renewal or “reform,” and is in no way reduced to the simple succession of magisterial statements from the popes.

For Benedict XVI, continuity is not the repetition of a dead letter, because Tradition is alive and is found in dialogue. For if, as Paul VI affirmed in the encyclical Ecclesiam Suam, “the Church becomes dialogue,”[5] continuity must be built as part of a life that flourishes in contact with the different cultures that human beings have known throughout history.

In this way, the continuity proper to the living Tradition of the Church goes beyond the rich encounter between Athens and Jerusalem. It is not only about continuity between reason and faith, between philosophy and revelation, or even about continuity between different periods of human history. Of course, all this was very important to Ratzinger. But his relationship with Teilhard also allowed him to see a cosmic continuity in which human beings walk toward the fullness of their existence in an integral way, that is, blossoming in all the dimensions of their being and culture.

Revisiting Ratzinger’s references to Teilhard throughout his work, we can see that rather than universal and modern reason, it is love and beauty that are central to the pope’s theology.

Ratzinger and the Teilhardian vision

Ratzinger began by praising Teilhard de Chardin because the Jesuit introduced to the West the awareness, already present in the Christian East, of a continuity between creation and redemption as cosmic events.[6]

It is true that in this 1968 work, Ratzinger seems to avoid directly quoting Teilhard’s texts, particularly The Phenomenon of Man, which had been published a decade earlier, in 1955. This is understandable in the context raised by Teilhard’s insights, sometimes formulated with a certain ambiguity. In any case, even after the 1962 Monitum,[7] it is significant that Ratzinger had a positive attitude toward the Teilhardian vision, shown by his by trying to listen to the Jesuit’s words, even when they were cited critically by others, such as Claude Tresmontant.[8] Indeed, the care in not quoting Teilhard’s texts directly, but only indirectly, confirmed Ratzinger’s esteem for him.

To return to the fundamental question, the young theologian referred to Teilhard in a positive way as early as his courses in the 1960s, especially regarding the relationship between Christology and anthropology.[9] Ratzinger appealed to Teilhard in seeking a total intelligibility of human life integrated with the evolution of the entire universe.

It is therefore a matter of seeking an intelligibility broader than the pure rationalism of certain ideologies that threaten us, such as positivist scientism. Rather than seeing phenomena isolated from one another, like some scientists do, Teilhard seeks to glimpse the future of this evolution whose outcome, in a sense, we are, and that we want to be. And what he sees, and teaches us to see, consists in an ongoing process toward union among all the beings that make up the universe.

To do this, it will be necessary to fully realize the dynamism that characterizes evolution. In order for the universe not to be absurd, we must lead its movement toward ultimate fulfillment.

Teilhard sees this movement with eyes that integrate the method of the natural sciences, but are not limited to it. To see the entire universe, including its entire future, we need to discover a total intelligibility, a coherence that integrates the natural sciences, philosophy and religion. Teilhard thus teaches us to see how evolution has always developed from different singularities and that new branches of the Tree of Life arise from the unification of different singularities. This means that we have had to go through a process of socialization linked to the growing complexity of life forms.[10]

It is about seeing the evolution of the universe and the progressive complexity of consciousness until it reaches the human being. Moreover, this socialization has not yet reached its climax. While in the past the universe seemed to have moved closer to human beings, now its evolution can continue on the basis of our free choices. If we do not want evolution to descend into absurdity, we are called upon to continue toward an ever more radical socialization of different elements.

One of Teilhard’s great lessons, according to Ratzinger, is to show us that the human “can be absolutely itself only by ceasing to be alone.”[11] With Teilhard, the evolution of the universe is intrinsically linked to Christianity, as it is Christian love that best accomplishes the socialization of different people. Evolution then can continue to be realized by different people socializing. Teilhard saw his task as to find the meaning of evolution through Christianity, its acme.

Ratzinger pointed out that the intelligibility Teilhard grasped is built on the practice of love, as a progressive union among all persons and also among all creatures, human and otherwise. Life is thus played out in a cosmic dimension.

When he discusses the resurrection of the body, Ratzinger takes up the Teilhardian vision to show us that this is about the victory of love. Resurrection is not the achievement of an autonomous superman, but rather is possible for those who who live by offering themselves, thus realizing the victory of life as a communion that unifies distinct persons.

Therefore, the continuity Ratzinger speaks of also concerns all dimensions of humanity and its cultures integrated into the history of the universe.

Teilhard and the continuity between ‘eros’ and ‘agape’

Among other theological sources, the connection between the Jesuit’s vision and Benedict XVI’s magisterium may be helpful in understanding why the theologian pope was concerned with defending love in all its dimensions. In this regard, it should be noted that Benedict XVI’s magisterium seemed to focus less on explicitly moral issues, at least compared to the pontificates of Paul VI or John Paul II.

The 2005 encyclical Deus Caritas Est now constitutes a decisive milestone in the magisterium of this third millennium. Speaking of love without complications, in a frank dialogue with philosophers such as Nietzsche, whom we had never seen appear in a papal document, Benedict XVI offers an apologia for eros. Outrageous, perhaps, but only to those who were quick to condemn Teilhard’s insights on the cosmic Christ.

If love were the only experience of eternity that we can have in this finite and contingent world, we would not be surprised that a pope could cite, without modesty or reserve the concept of eros. In his first encyclical in 2005, which can be called “programmatic,” the theological virtue of Christian love appears as a unity of eros and agape. Benedict XVI’s balanced position prevents him from belittling either expression of human love. To the extent that love is experienced as “a single reality,” it is a human experience with distinct dimensions.[12]

There is giving and receiving. We must give ourselves to the other as well as receive the gift offered by the other. For the theologian pope, this is true both of purely human love and of the religious experience of those who feel loved by God. To unite ourselves with the beloved, who in turn loves us, is both to possess him or her and to allow ourselves to be possessed by him or her. This is why oblative love is never opposed to the love of possessive desire. Agape finds its condition of possibility in eros, and without it, oblative love degenerates into violence. When the pleasure of possessing the other is realized in the act of offering oneself totally to him or her, there is genuine communion. This is how the Cross of Christ meets the glory of God, just as the sacrifice of agape, love meets the enjoyment of eros at the banquet of Holy Mass.

It is true that no reference is made to Teilhard in the encyclical Deus Caritas Est. However, Benedict XVI remains close to the Teilhardian vision, the attraction to God whereby the human person feels in tune with the entire universe. In the words of the theologian pope, “love embraces the whole of existence in each of its dimensions, including the dimension of time. It could hardly be otherwise, since its promise looks toward its definitive goal: love looks to the eternal. Love is indeed ‘ecstasy,’ not in the sense of a moment of intense joy, but rather as a journey, an ongoing exodus out of the closed inward-looking self toward its liberation through self-giving, and thus toward authentic self-discovery and indeed the discovery of God.”[13]

How can we not see Teilhard’s presence in this vision of love as a path that fulfills us in all dimensions of our existence? Of course, one could argue that this is simply Augustine. However, we should not forget that Ratzinger, as a theologian and teacher, embraced the Franciscan school, and not only Augustine. So dear to Teilhard, this school was a meeting place between the theologian-turned-pope and the Jesuit paleontologist. Witness the habilitation thesis in which Ratzinger argues, with St. Bonaventure, that the future of history is not non-essential, but constitutes the fundamental possibility so that the meaning of life can flourish from the free actions produced by love.[14]

Faith as an experience of beauty and hope

For Teilhard, love is not only realized in the final state of the evolutionary process; rather, it is a dynamic of love, a mixture of attraction and oblation of individuals uniting into a social body. As the body of Christ, the Church consists of this union of all creatures, including non-human creatures.

In this sense, the praise of God within the worship that is due to God is realized through a cosmic liturgy where the human being already has the experience of being harmoniously linked to all creatures, and in a process that reaches its goal in the intimate and total communion of everything in God and with God. Already the young theologian Ratzinger corroborates the Teilhardian interpretation of St. Paul, especially in the context of the liturgy: “The cosmos is also movement, going from a beginning to an end, and in this sense it is history. This notion can be understood in different ways. Teilhard de Chardin, for example, relying on the modern conception of evolution, described the cosmos as a process of ascension, made up of successive unions. […] From there, Teilhard offers a new and personal interpretation of Christian worship: the transformed host he sees as the anticipation of the transformation of matter and its deification into Christological ‘fullness.’ The Eucharist would somehow give direction to the cosmic movement; it would anticipate its goal and at the same time hasten its fulfillment.”[15]

Ratzinger thus follows Teilhard’s interpretation of the Letter to the Ephesians, seeing love as the energy that leads to the flowering of life toward its fullness in God, its omega point. The same is true of the theologian pope. In a homily commenting on a passage from a letter of the Apostle of the Gentiles, Benedict XVI explicitly quotes Teilhard’s name to emphasize the cosmic character of the Eucharist: “This is precisely the meaning of the first part of the prayer that follows: ‘Let your Church offer herself to you as a living and holy sacrifice.’ It is a reference to two texts from the Letter to the Romans. […] We ourselves, with our whole being, must be in worship and sacrifice, returning our world to God and thus transforming the world. The function of the priesthood is to consecrate the world so that it becomes a living host, so that the world becomes liturgy: that the liturgy is not a thing beside the reality of the world, but that the world itself becomes a living host, becomes liturgy. This is the great vision that Teilhard de Chardin also had: eventually we will have a true cosmic liturgy, where the cosmos becomes a living host.”[16]

Benedict XVI is undoubtedly referring to The Mass on the World, where Teilhard describes an experience, which we can describe as mystical, an experience of wholeness in harmony with the universe and in communion with God. In this sense, going beyond being confined by a purely rational intelligibility of the entire universe, the theologian pope frees himself, with Teilhard, from any possible scientific positivism. It is a matter of seeing and letting oneself be seen from a complex experience of love, beauty and hope.

The Mass on the World is a poetic and mystical text in which Teilhard reveals to us that his worldview was never an exercise of abstract or speculative reason. It is about living communion with God in the unity of the cosmos moving by attraction toward its omega point. In the words of Teilhard himself, “This total Host that Creation, moved by your attraction, presents to you at the new dawn. This bread, our effort, is in itself (I know it well) nothing but an immense disintegration. This wine, our pain, is unfortunately so far nothing but a dissolving drink. But, at the bottom of this formless mass, you have put (I am sure, because I feel it) an irresistible and sanctifying aspiration that, from the ungodly to the faithful, makes us all exclaim together, ‘O Lord, make us one!’”[17] The overall vision that Teilhard teaches us includes an aesthetic dimension in which authentic faith is realized. Continuity, so much evoked in connection with Ratzinger’s theology, also concerns this unity of the human person, in all dimensions of existence.

This connection with Teilhard as mystic and poet helps us deepen the importance of beauty in Benedict XVI’s speeches. “Authentic beauty, however, unlocks the yearning of the human heart, the profound desire to know, to love, to go toward the Other, to reach for the Beyond.”[18]

The experience of beauty frees us, in this way, from a closed scientific determinism where faith has no place. To open the horizons of reason, we must have this experience of harmony with the whole cosmos in God. The Teilhardian vision then consists of a kind of performative phenomenology, in the sense that it never describes a mere phenomenon, but instead leads to an experience that the reader, perhaps, has not yet reached. It is the human experience, very human, of those who are amazed by so much beauty in nature, which welcomes us and we welcome on a path yet to be traveled.

Teilhard could have subscribed to this statement by Benedict XVI on beauty: “Beauty, whether that of the natural universe or that expressed in art, precisely because it opens up and broadens the horizons of human awareness, pointing us beyond ourselves, bringing us face to face with the abyss of Infinity, can become a path […] toward God.”[19]

Thus, the gratuitousness of beauty allows us to live, henceforth, beyond the calculating logic of those who control, design or transform everything to their liking. To continue the evolutionary path toward the full realization of the universe is more loving than dominating. More than understanding all the sciences, more than being able to reproduce through technology everything that has already happened in the course of evolution, it is more about the freedom to unite with one another through charity.

Conclusion: how to look at life

Teilhard and Ratzinger followed very different paths within the Church. While one lived from exile to exile trying to get his insights accepted within the Church, the other soon became a bishop and cardinal; while one devoted himself to living out his faith in the modern world by exchange with fellow scientists, the other spent much of his life in positions of Church government. However, both have been misunderstood. While one has often been misunderstood for the ambiguity of his expressions, which seemed to put in question the orthodoxy of his vision, the other has often been considered a rigid conservative because of the rigor of his theology. But in reality – although each in his own way – both sought to grasp all that the science and culture of their time offered and to embody the Christian faith in the modern world.

To do this, rather than talking about God in the categories of the past, both of them focused on the question of the human being in the world. God emerges only in relation to the fullness of the human, otherwise salvation would no longer be the focus of Revelation.

Whether we like it or not, Ratzinger’s theology corroborates and supports Teilhard’s vision of the universe evolving toward God, its omega point. The continuity the two authors affirm obviously concerns the living Tradition of the Church. But it is also a cosmic continuity that extends to all of creation. Historical continuity is related to the communion between all beings that make up the universe and walk together toward God. Ratzinger’s theology and the Teilhardian vision seek to introduce everyone to this path that leads to mutual communion and fulfillment.

In the game of chess we tend to avoid what are called “pawn islands.” An isolated pawn, with no others around, becomes too vulnerable, no longer has any value; it is as if it does not exist. In our opinion this is a beautiful metaphor of human nature that Teilhard shows us in his vision. We cannot isolate humans from their environment. It makes no sense to think of ourselves and our individual interests, cut off from everything else, since the other creatures, the other components of the cosmos, are part of an irreducible unity.

If life were a chess game, one should not play it alone. This is what Teilhard teaches us: not only to see differently, but to play the game of life as a team. Victory does not only depend on the isolated, autonomous individual, nor the collective that constitutes humanity. For life to truly triumph, we need God, our omega point, and to remain in communion with God. Without God, life would be lost, as in the solitude of the desert without encounters.

By showing the path that leads the energy of love to its fullness, Teilhard invites us to believe in life. Instead of despairing or rebelling against the absurdity of existence, like Sisyphus, ineffectively attempting to roll uphill the rock that always and endlessly rolls back down the slope, Teilhard’s vision fills us with hope, opens us to the triumph of life that evolution has given us. As a pope or as a theologian, Ratzinger, in line with Teilhard, agreed to look at life in this way.

Andreas Lind SJ is a Fellow of the Faculty of Arts, University of Namur, Belgium.

Reproduced with permission from La Civiltà Cattolica.

[1]. Pierre Teilhard de Chardin was born in Sarcenat, France, on May 1, 1881. He entered the Society of Jesus in 1899 and was ordained a priest in 1911. He was a stretcher-bearer during World War I and, for his heroism, was awarded the Legion of Honor. He taught geology at the Institut Catholique in Paris but had to leave France because of the Society’s concerns about his evolutionist orientation. From 1926 to 1946 his life was spent in China, where he engaged in extensive research in the field of paleontology that brought him international fame. After World War II he returned to Paris. He traveled several times to North America and South Africa. Finally he moved to the United States. He died in New York on April 10, 1955, on Easter Day, as he had wished. He is the author of numerous scientific studies. Most of his works of philosophical-religious content appeared after his death and have been translated into many languages. From June 2-4, 2023, the Teilhard de Chardin Center, dedicated to the dialogue between science, philosophy and spirituality, was inaugurated at the Saclay science hub, 20 kilometers south of Paris.

[2]. In this article the author mostly quotes Joseph Ratzinger from the French edition of his works, which have been translated into many different languages. In particular the best known of them, Einführung in das Christentum, has been translated into 17 languages. The French edition is titled: La foi chrétienne hier et aujourd’hui, transl. E. Ginder – P. Schouver, Paris, Cerf, 2005. The reference for the quoted words is on p. 162. An English translation, entitled Introduction to Christianity was prepared by J. H. Foster and published by Burns and Oates, London, in 1969.

[3]. J. Ratzinger, Les principes de théologie catholique, Paris, Parole et Silence, 2008, 374.

[4]. Benedict XVI, Meeting with the world of culture, Lisbon, May 12, 2010. https://www.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/speeches/2010/may/documents/hf_ben-xvi_spe_20100512_incontro-cultura.html#

[5]. Quoted by Benedict XVI, ibid.

[6]. Cf. J. Ratzinger, La foi chrétienne hier et aujourd’hui, op. cit., 40.

[7]. This is a “warning” statement by the then Congregation of the Holy Office, regarding the writings of Fr. Teilhard de Chardin.

[8]. Indeed, Ratzinger quoted Teilhard through the work (in the German version) by C. Tresmontant, Einführung in das Denken Teilhard de Chardins, Alber, Freiburg i.B., 1961.

[9]. Cf. D. Lambert – M. Bayon de La Tour – P. Malphettes, Le phénomène humain de Pierre Teilhard de Chardin. Genèse d’une publication hors normes, Brussels, Editions Jésuites, 2022, 270, no. 720.

[10]. Cf. J. Ratzinger, La foi chrétienne hier et aujourd’hui, op. cit., 158-165.

[11]. Ibid., 160.

[12]. Benedict XVI, Encyclical Letter Deus Caritas Est, December 25, 2005, no. 8. https://www.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/encyclicals/documents/hf_ben-xvi_enc_20051225_deus-caritas-est.html

[13]. Ibid., no. 6.

[14]. Cf. J. Ratzinger, La théologie de l’histoire de saint Bonaventure, Paris, PUF, 1988, 182. In Italian we have: J. Ratzinger, Saint Bonaventure. La teologia della storia, edited by L. Mauro, Florence, Nardini, 1991; and especially vol. II of J. Ratzinger’s Opera Omnia: L’idea di rivelazione e la teologia della storia di Bonaventura, Vatican City, Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2017.

[15]. J. Ratzinger, L’esprit de la liturgie, Genève, Ad Solem, 2001, 24-25.

[16]. Benedict XVI, Homily during the celebration of Vespers in the Cathedral of Aosta, July 24, 2009.

[17]. P. Teilhard de Chardin, La messe sur le monde, in Hymne de l’univers, Paris, Éd. du Seuil, 1961, 23. In English: The Mass on the World in Hymn of the Universe, New York, Harper and Row, 1961.

[18]. Benedict xvi, Address to the artists, Sistine Chapel, November 21, 2009. https://www.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/speeches/2009/november/documents/hf_ben-xvi_spe_20091121_artisti.html

[19]. Ibid.