A few days before Pope Francis died, I was talking to a friend who is a Marist Brother. He mentioned he’d been visiting an American cardinal who works at the Curia. I didn’t recognise the name. “He might be the next pope,” my friend told me. An American? No chance (and God help us), I thought to myself. But a few weeks later, I heard Robert Prevost’s name again, as it was read from the balcony of St Peter’s.

While most of the world was stunned by the choice of Chicago-native Cardinal Robert Prevost as pope, I suspect no one who knows Brother Mark O’Connor, FMS, would be surprised to hear that he had had coffee with him not long before, or that he had sources in Rome saying this was the next pope. Vicar for Communications in the Diocese of Parramatta, he’s pretty far flung from the Appian Way, but somehow, he always seems to have his ear to the ground and a travel bag ready to go.

He was in Rome once again in 2013, a few weeks after Francis was elected. While there, he ran into a nun serving in the office of the Union of Superiors General of Women. Their leadership had just met with Francis, the first time in many years their group had been received by a pope. (Meanwhile the Major Superiors of Men had had any number of such meetings.) “I’m so glad you’ve been elected,” she told Francis. “I have to say I was almost having a crisis of faith about the Church.” At this, she told O’Connor, the pope burst out laughing. “You’ve only had one crisis of faith?,” he asked. “I have one every week.”

O’Connor is celebrating 50 years in the Marists this year, and also 40 years of running the Hélder Câmara Lectures, which brings prominent Catholics from around the world to Australia each year to deliver a series of talks and seminars around the country, including the Hélder Câmara Lecture at Newman College at the University of Melbourne. And to spend any time with him is to hear many anecdotes from across those 50 years involving a pantheon of the church-famous and seasoned battlers to rival the communion of the saints. There’s something of the magpie about him, a hungriness for moments like these. But as we talked on Zoom it became clear, what attracts O’Connor aren’t things that are shiny. It’s moments that offer hope.

The light in the darkness

Mark O’Connor was a suburban kid from Melbourne when he met the Marists at secondary school in 1970. Tennis at the time was far more interesting to him than academics or religion. “I was playing tennis four or five nights a week.” But, almost to his own surprise now, he decided to spend Years 11 and 12 at the Marist Juniorate in Bendigo. “It was Mass every day and strict; you weren’t allowed to go to socials or dances”. Not exactly the standard fare for a school boy, but O’Connor stayed with it, and ended up at the Marist novitiate in Mount Macedon, where he was tasked among other things with feeding the cows. Still, as vows approached, he found himself unsure about what he wanted. “I was 20, and I don’t think I was particularly clear about who I really was.”

With the Marists’ permission, he paused his formation. Eventually, he began six months of Clinical Pastoral Education. Working as a chaplain at a hospital and processing his experiences with others in the program was revelatory. “It gave me a sense that you meet God in people, that grace is not a thing, it’s a person you encounter in others and in events, the kind of Kairos moments of your life.”

Br Mark O’Connor FMS, Vicar for Communications in the Diocese of Parramatta. Image: Diocese of Parramatta

Those months taught him something else as well, something that all these years later also seems to remain at his core: even in the darkness, there is light. “You know how when you go into a dark room, your first reaction is you can’t see anything and you panic looking for the lights? I think I was a lot like that for the first quarter century of my life,” he explained. “But gradually I realised that if I sat in the darkness long enough, I would see objects, because my eyes would become acclimatised.”

“My life was always going to be, and it still is, ‘through a glass darkly’,” he said. “But working through to some degree my own inner darkness meant that I could see that there were possibilities along that journey.”

In the presence of God

There were times in talking to O’Connor that I myself wanted to hit pause to write down some of the beautiful ideas he has collected over the years. “St Teresa of Ávila once said, ‘Suffering passes. Having suffered never passes’,” he tells me at one point. At another, he’s recalling a story of Paul Eddington, the British actor from Yes, Prime Minister. Interviewed shortly before the end of his life, cancer ravaging his body, he was asked what he’d like the epitaph on his tombstone to read. He replied: “He didn’t do much damage.” Says O’Connor, “I identify with that.”

Time and again, though, O’Connor’s stories come back to one person in particular, Brazilian Dom Hélder Câmara, who served as Archbishop of Olinda and Recife from 1964 to 1985. Known as the “bishop of the slums” for his outreach towards the poor and condemnation of the dictatorship that ruled Brazil while he was in office, Câmara was one of the primary writers of Gaudium et Spes at Vatican II. Shortly before the Council ended he and a number of other bishops made “The pact of the Catacombs”, which eschewed all titles and privileges and vowed they would live in the poverty experienced by most of their flock. And he’d done so. He famously said: “When I give food to the poor, they call me a saint. When I ask why the poor have no food, they call me a communist.”

His formation complete, O’Connor spent much of the early 1980s working as a secondary school teacher. He saw his students losing hope in the Church. “They were spending 12 years in Catholic schools but leaving completely alienated from the institutional Church, despite the best efforts of all sorts of people,” he recalled. He proposed the Marists begin a new ministry for young adults, including a biennial Marist Youth Festival, and he wanted Câmara to be the main event. “I thought that we should bring out inspiring figures to just tell their stories.”

It took more than a year and other speakers in between, but in 1985, Câmara did come out. “He could barely speak English and he looked a bit like E.T., but he had this charisma,” O’Connor remembers. “You felt somehow that you were in the presence of God.”

While Câmara was visiting, Brazilian liberation theologian Leonardo Boff was silenced by Pope John Paul II and Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger. At a press conference in a parish hall in Fitzroy, journalists deluged Câmara with questions about the event. “Dom Hélder, isn’t it shocking, isn’t it terrible, you must be very upset,” O’Connor recalls them asking. “How can John Paul II be so authoritarian?” In response, Câmara sat quietly, taking it all in. “Then he looked up and he simply said, ‘It’s not easy being pope’,” O’Connor remembers. “That was it.”

Câmara was intimately familiar with injustice, whether political or ecclesial. “Each day he would celebrate the Eucharist, and at the moment of the consecration he would literally weep,” O’Connor told me. “You could see the paschal mystery being lived out in his body and in his connection with the suffering of the crucified people where he was living.”

Soon after he returned home from Australia, Pope John Paul announced his replacement, a man who would systematically strip away all of the reforms Câmara had instituted. “But he still had such largeness of heart, he felt sorry for John Paul II and Ratzinger. He wasn’t a win/lose person.”

Finding freedom in the broken places

O’Connor’s experiences with Câmara convinced him he was onto something. “You actually felt hope,” O’Connor says. “It wasn’t just an idea, a beautiful ideology. It was embodied in him.” He began to pursue other inspiring figures in the Church to come to Australia. In 1986, he wrote to Italian Cardinal Carlo Martini, the Jesuit archbishop of Milan. Martini politely declined. A year later, O’Connor wrote to him again. Again, he politely declined. Undeterred, O’Connor wrote to him again each of the next six years, then finally with the help of benefactors, travelled to see him. And Martini came two years later. If you want people to come to you, O’Connor learned, you have to go to them. His religious brothers don’t mind kidding him about his frequent travels, to which he sometimes jokingly replies with a saying of the Marist Brothers’ founder, Marcellin Champagnat: “Our diocese is the whole world.”

But, supported by donors, he’s also gotten academics, writers, bishops, and other luminaries from every continent and part of the world to travel around the world and spend weeks in Australia, something that otherwise only a wealthy university might be able to do. And even for such institutions, the names he’s gotten – Margaret Silf, Robert McElroy, Luis Tagle, Nathalie Becquart XMCJ, Monsignor Professor Tomáš Halík, Oscar Rodriguez Maradiaga SDB, Christopher White – would be impressive. And those are just some of the names from the last 10 years.

A composite image of presenters of the Hélder Câmara Lecture series since 2019 that have also presented in the Diocese of Parramatta: (Top L-R) Dr Austin Ivereigh, Dr Bonnie Thurston, John Cardinal Dew, Christopher Lamb, Sr Nathalie Becquart XMCJ, Christopher White and (Bottom L-R) Monsignor Tomáš Halík, Dr Myriam Wijlens, Mauricio López Oropeza, Dr Nora Nonterah and Stephen Cardinal Chow SJ. Images: Diocese of Parramatta

For this year’s 40th anniversary he’s bringing in three speakers: Mauricio López, the lay leader of the Amazonian Ecclesial Conference, a new body consisting of bishops and lay people across the Amazonian region, kicked off on 30 July with a lecture entitled “How is the future of the Amazon the future for all?” at Newman College (Lopez also spoke at St Patrick’s Cathedral in Parramatta on 23 July); Ghanaian ethicist Nora Nonterah gave “Listening to the Wisdom of Women: a conversation about discipleship, leadership, and synodality from an African lay woman’s perspective” at St Patrick’s Cathedral in Parramatta on 2 September, and Newman College, on 3 September; and Cardinal Stephen Chow, SJ, the Bishop of Hong Kong, will be doing public interviews with Fr Richard Leonard, SJ, at St Patrick’s Parramatta on 15 September, and with Newman Rector Fr Dan Madigan, SJ, on 16 September.

I wondered about the criteria O’Connor uses to decide who he wants. He’s had progressives and conservatives. Many have been passionate advocates for justice of one form or another, but not all. Is there some sort of common denominator? “The people who I’ve caught faith from, who have passed on faith to me, are people who are not necessarily saints, they can be quite flawed,” O’Connor reflects. What they have in common is “authenticity in the Spirit.” And after many years of doing these talks, he’s realised that authenticity has a lot to do with suffering. “Only grief permits newness,” he says, quoting scripture scholar Walter Brueggemann, about whom he wrote a Master’s degree. “The Israelite experience in Exodus is that when they are able to articulate their pain and cry out, ‘We have been harshly dealt with,’ that is the beginning of their liberation.”

So many of the people he’s brought to Australia have had that experience of a suffering that is creative and ultimately liberates. He points to Chicago Cardinal Joseph Bernardin, who came in 1995. Two years earlier, Bernardin had been accused of abuse. Three months later his abuser recanted. Where the public vilified the man, Bernardin invited him to come and visit him. They met for two hours, and Bernardin said afterward: “This has been one of the most memorable experiences I’ve ever had… a wonderful moment of reconciliation between Steven, myself and the church.” Said O’Connor of Bernardin: “He went through the crucifixion of that false accusation, and there was a kind of a kenosis,” of self-emptying. “He died a free man.”

In 1988, Cardinal Basil Hume, OSB, came from Westminster, UK. At one point he told the young people about a nun he had known as a child who taught him to see God as a figure that’s always there, watching and knowing everything he did. If he ate an apple before dinner after his parents told him not to, they might not know it, she noted, but God always would. “She was very well-intentioned,” O’Connor recalls Hume explaining. “She was trying to teach him the difference between right and wrong.”

But then, Hume went on, in what seemed almost like a postscript, “It took me 45 years to recover from that story.” Until his 50s, Hume revealed, “I still unconsciously thought of God as the person who, if I did something right, he’d give me a tick; and if I did something wrong, he’d give me a cross. It was only when I was in my early 50s that I realised that actually, God is the sort of person who would have come up to me, tapped me upon the shoulder and said, ‘Basil, You look very hungry. Take two apples’.”

“Hélder Câmara, Basil Hume, Jean-Marie Lustiger (Cardinal archbishop of Paris and convert from Judaism, who came in 2001), with his mother being taken away by the Nazis and never knowing what happened to her: You get beyond the surface with just about every one of them, and there’s a story of the paschal mystery that is underpinning their voice. Francis too: He suffered, and that suffering made him creative.”

O’Connor recalls the end of Georges Bernanos’ Diary of a Country Priest, which he re-reads every few years. Dying in his friend’s arms, the country priest – who has suffered greatly himself, and come to appreciate the agonies experienced by those he has served – realises “How easy it is to hate oneself. True grace is to love oneself, in Christ.”

The book ends with his final thought: “Grace is everywhere.”

To feel hope

“I’m basically a restless soul,” O’Connor admits, and someone who has experienced his fair share of loneliness, too. Earlier in life, “I think perhaps I had unconsciously come to think that someone else could fill my emptiness,” he says. But gradually, he’s come to a different understanding: “What I feared might be emptiness is actually space, and the loneliness a creative solitude.”

Travelling around the world, engaging with Catholics of all shapes and sizes has been life-giving, that experience of the Holy Spirit living not up in Heaven somewhere but precisely in the interactions between people that he first saw working in that hospital in Melbourne. “It gives me reason to get up and continue on,” he says. It’s also taught him something important about the Church: “One can still find hope in the Catholic Church, if you look for it.”

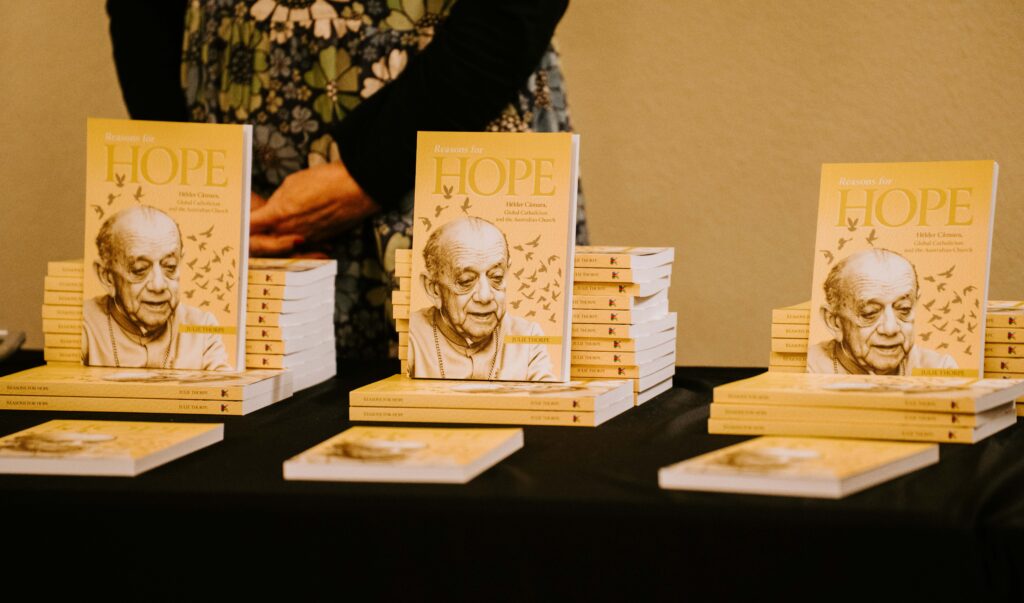

As part of the 40th anniversary, author Julie Thorpe has written a book Reasons for Hope chronicling the history of the Hélder Câmara series. O’Connor points to a line at the end of the acknowledgements which captures the intent of his own “small, modest effort” these 50 years as a Marist Brother.

Reasons for Hope: Helder Camara, Global Catholicism and the Australian Church, by historian Dr Julie Thorpe. Image: parallaxmedia

“This book,” Thorpe writes, “doesn’t seek to analyse, or argue, or explain primarily, much less follow a particular ideological rule, but amidst the myriad unsettlements and pain in the Church and in the world, to feel hope.”

Jim McDermott is an American culture critic and screenwriter.

This is an edited version of an article that first appeared in Eureka Street. It is used with permission.

This article was originally published in the 2025 Season of Creation | Spring edition of the Catholic Outlook Magazine. You can read the digital version here or pick up a copy in your local parish.