Martin Place is the bustling heart of Sydney’s business district but few know the story of Sir James Martin, one of New South Wales’ first self-made leaders.

His life demonstrated talent, determination, the opportunities of early Australia and also symbolised the tension between humble origins and achieving worldly success.

Martin’s father worked as groom in Governor Brisbane’s stables. The Martin family lived in a cottage near the stables, in a world where Irish Catholics were at the bottom of society.

James Martin’s extraordinary tenacity was clear from a young age, when he walked and hitch-hiked 21 kiloetres from the stables of Government House, Parramatta, to his private school next to Hyde Park.

Walking the entire daily commute would have taken almost ten hours, covering the same distance as a marathon. He did ‘everything he could’ to further his education, including staying overnight in the city.

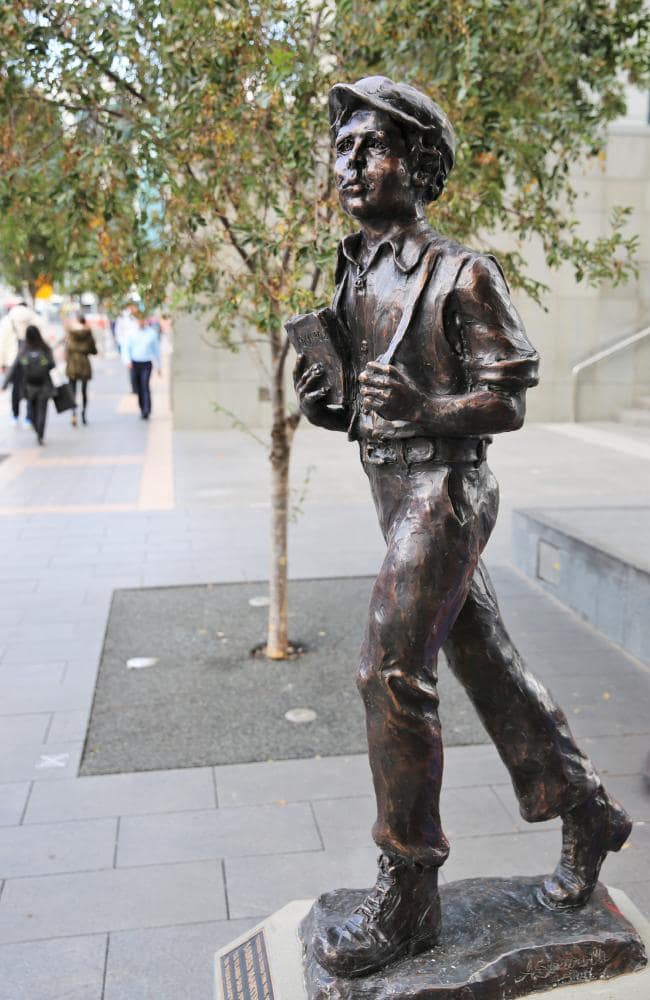

A new bronze statue in Parramatta commemorates Martin’s childhood, thanks to philanthropists John and Patricia Azarias, who also founded the annual James Martin Oration, recognising his contribution to law, letters, cultural development, social reform and colonial self-government.

He was the first non-English Chief Justice of NSW and to this day is the only person to have served as Premier and Chief Justice of New South Wales.

At the age of 18, Martin began his literary ascent with the publication of a book of short essays, The Australian Sketchbook, dedicated to George Nichols, owner of The Australian newspaper, where Martin would one day be editor.

The book frequently alludes to classics of the Western Canon and the concluding chapter displays Martin’s delight in Christmas Day, revealing a strong religious outlook, “Fancy even imagined that a joyous smile played on his radiant disc [of the sun]…”

“Let atheism laugh and folly smile – he who could not see any charms in a moment such as this, is ignorant of a pleasure, which conscious security and unrestrained indulgence would never enable him to enjoy.”

An inclination to non-conformist Christianity suggested itself when Martin virulently penned attacks on the Church of England’s Bishop Broughton, supporter of Martin’s political opponents Governor Gipps and Premier Cowper.

Martin lambasted Bishop Broughton for being a member of the Oxford Movement, a revival of Roman Catholic theology and ritual within the Church of England, satirising him as “our Australian Pope, Patriarch and Pontiff”.

By 1850, Martin’s prominence and lapsed Catholic faith brought him into conflict with Fr John McEncroe, Catholic education pioneer and founder of the Freeman’s Journal, which continues today as the Catholic Weekly.

Fr John McEncroe strongly criticised non-practising Martin as “a living example of the effects of an education not based upon religion”.

Martin’s humble family were strongly Catholic but at 33, Martin made a decisive break with the Catholic Church when he married Isabella Long in St Peter’s Anglican Church, Cooks River.

In a landmark event for relations between the Irish and English in Australia, Premier and Attorney-General Martin prosecuted Henry James O’Farrell, the Irishman who attempted to assassinate Queen Victoria’s second son, Prince Alfred, on his tour of the Colony of New South Wales.

Martin was knighted in commemoration of the tour and became Sir James Martin.

Alfred Park, Parramatta, Alfred Park, Central Station and Royal Prince Alfred Hospital were all named in the Prince’s honour.

Martin was buried at St Jude’s Anglican Church, Randwick before being transferred to Waverley Cemetery. The bitter disappointment of Irish Catholics at the religious and cultural betrayal of their former political favourite continued well after Martin’s death.