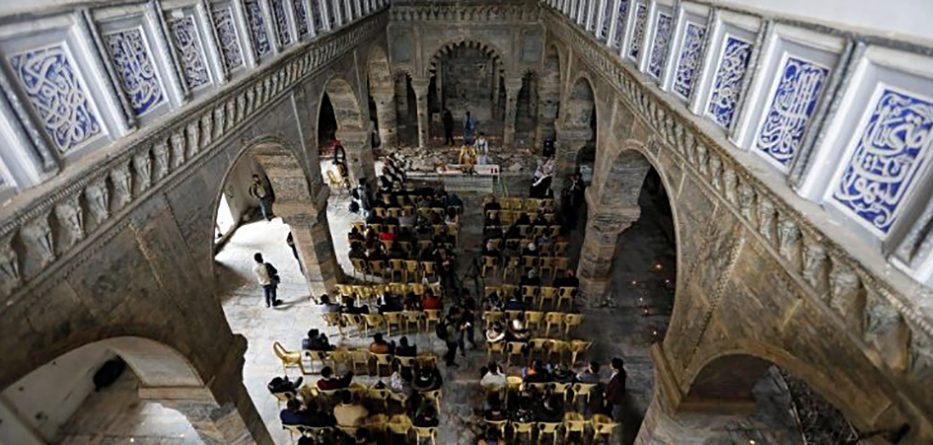

Pope Francis’ visit to Iraq (5-8 March 2021) will bring to the attention of Christians around the world and of the international community the issue of the survival of Christian communities in Middle Eastern regions that, because of wars, tribal conflicts and poverty, risk disappearing forever. These are very ancient communities, many of apostolic foundation. Archbishop Bashar Warda of Erbil of the Chaldean Catholic Church of Iraq and founder of the Catholic University of Erbil, said in a recent interview: “Before 2003 there were more than 1,300,000 Christians in Iraq. Today fewer than 300,000 remain. Where there is no work and rights are not guaranteed to minorities, and with security lacking, flight and diaspora are unfortunately the choice of many.” This is the current situation, although, as we shall see, the emptying of the Middle East of its Christian inhabitants has been going on for much longer.

The phenomenon of Christian migration in the last century involves almost all the countries of the Middle East, from Turkey to Egypt, passing through Syria, Lebanon, Palestine and, in recent times, in a worrying way, Iraq. Here are some discouraging facts about the size of this exodus: toward the end of the Ottoman Empire, in 1914, Christians were about 24 per cent of the population, and reached 30 per cent in the area of the so-called “greater Syria”; in the 1990s in the Middle East, Christian residents were less than 5 per cent. Today, following the wars in Iraq and Syria, and after the crisis in Lebanon, their numbers have again very much decreased. This means that this region has been deprived of a culturally and spiritually very rich presence, which contributed to creating the national identity of those countries.

In some of these countries, the independence obtained in the years following the Second World War had kindled in the intellectual elites and political activists, both Muslim and Christian, the hope of being able to establish in their own countries secular, democratic state systems, thus transitioning from an archaic form of government based on privilege (and often on abuse), to more modern systems, up to that moment strongly claimed by nationalist movements. In these countries, however, the newly implanted democratic order generally had a short and difficult life, and authoritarian forms of government, marked by strong nationalism, rapidly emerged, especially in countries such as Egypt, Syria and Iraq.

To continue reading this article go to La Civilta Cattolica.