What is evangelical about a church that, in the eyes of many, is nothing but a club only for men who cover for each other?

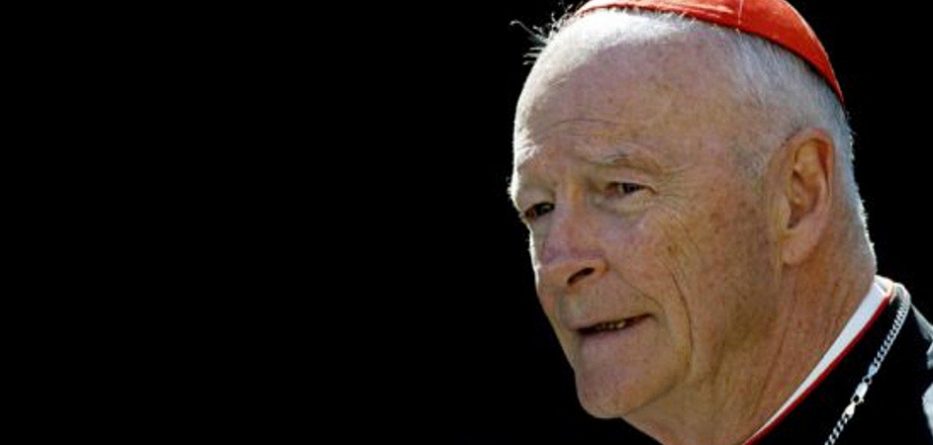

In a couple of sleepless nights, I read the 449 pages and 1,410 notes (the devil, as they say, is in the detail) of the Vatican report on former US cardinal Theodore McCarrick.

I had anticipated that it would be depressing reading, yet we must read the worst circumstances of the time in which we live and fully carry the weight and feel the responsibility. I write under an interior impulse. I feel that the Catholic Church, starting with its leaders, can no longer wait. Either structural changes are promoted (beyond those at the level of conscience, as is obvious) or this crisis will not be overcome. Already too many have distanced themselves from ecclesial life and the practice of faith.

I vividly remember meeting McCarrick in 1998 in Hong Kong. It was after he returned from an important trip to China on behalf of then-president Bill Clinton (a trip mentioned in the report). The auxiliary bishop of Hong Kong, John Tong, included me among the guests of a dinner for few people. Also present were two American missionaries, my colleagues at the Holy Spirit Study Centre where I worked as a researcher, and a priest accompanying McCarrick. The latter was then bishop of Newark and already known by many. He told us at length about his trip and his skills seemed indisputable to us. In fact, for many decades McCarrick managed to have the most powerful American politicians and Vatican leaders on his side.

From reading the report, I get the painful impression of a disturbing character who moves in a disturbing world. In this story, the worst evils of the Catholic Church seem to have got together: clericalism, machismo, paternalism, abuse of power, sexual abuse, minors’ abuse, corruption, lies, perjury, careerism, ambition, hypocrisy, silence, irresponsibility, sloppiness … and so on.

In the end, I was not even surprised. I say this with regret. Anyone who was informed enough, even without knowing the obscure details, could well anticipate what had happened, the mechanism behind the whole awful affair. But it does not change the bitterness, sadness, disappointment and sense of helplessness. I find that these stories, which involve the highest leaders of the Church, truly unbearable.

The testimony of Mother 1 particularly moved me. A mother of many children, she is a woman crushed by the pervasiveness of a male chauvinist church. She and her husband, very devoted, welcome the young bishop into their home as one of the family. In a short time, with the eyes of a mother, she understands everything that the Vatican took 40 years to understand. The mother realises that McCarrick doesn’t really care about their daughters: obviously, it is not pastoral charity that drives him. He has eyes, enthusiasm and initiatives only for males and involves them in an invasive way. And then she sees what she didn’t want to see. She cannot believe it, and she doesn’t know who to talk to. She fears retaliation from him as he is powerful.

The mother does not know how to move into a men’s club. And this is what the Church must have seemed to her. She employs inadequate means: writing anonymous letters to a large number of church authorities. She does not know what else to do, convinced that no one would really listen to her. What is evangelical about a church that, in the eyes of many, is nothing but a club only for men who cover for each other? What still needs to happen to acknowledge that the people of God include women and men and that all the baptised participate responsibly and with equal dignity in the life of the Church?

The devotion of Mother 1 made me think of my father, an extraordinary believer, father of 10 children, four of whom entered a seminary. He had great respect for the dignity of the priesthood and a boundless trust in priests and bishops. The idea that they could do harm could not even touch him. In just a few decades this precious heritage, which I have shared, has been lost. And abuse of minors is top among the causes of the disaster. Now priests and bishops have zero reputations in various social groups and nations, among the majority of young people, and even in ecclesial groups. I saw it dramatically in various places, including the former Catholic country Ireland in the summer of 2019; the same, I am afraid, is happening now in Poland.

Justifying this tragedy by affirming, as I often hear or read, that the Church is made up of saints and sinners, and therefore that this was an isolated incident, is an easy way out to evade the gravity of the situation. It is not an isolated incident. And these reassurances seem to me an unbearable superficiality and an all too easy alibi. History shows it: when the Church did not meet challenges with sincerity, timing and effectiveness, irreparable damage occurred. It caused irrecoverable divisions, with entire nations lost to the Catholic faith, schisms (overt or silent) and distancing from the life of faith of too many people.

In 2003, when the media hype about the abuse by priests broke out in Hong Kong in the wake of Boston’s Spotlight scandal, I was called to write about it and discuss it in a few television broadcasts. The Hong Kong curia gave me material to read in preparation. In a few days, I learned a lot. Seventeen years have passed, and we know much more. How irritating to see clergymen — even with very high responsibilities in the Vatican — address these issues with reckless superficiality, without really knowing what they are talking about, without perceiving the gravity, the severity of the pain of the victims or the gravity of the scandal for God’s people.

As coordinator of the PIME commission for ongoing formation, I invited competent people to speak about the problem of the abuse but not without running into those who, listlessly, would tell us: “But enough of these things!”

As dean of the PIME theological school, I have pledged to do the same. Now our academic curriculum includes a seminar on the protection of minors and vulnerable adults, held by the best experts available in Milan. We have introduced a course on “Women, the Bible and theologies” which has the ambition of clericalising the mentality with which too many approach the ordained ministry. For the same reason, we have increased the number of female teachers and lay teachers.

McCarrick’s supporters believed in his innocence despite being aware of his occasional practice of sleeping with seminarians and priests. For them, it was just imprudence. But they also admitted that it was evident that the bishop had a boundless ambition. Yet for them, it was a venial fault. Commentators on the report agree that those who kept quiet and lied about McCarrick, including bishops (the names of those who lied have been included in the report), seminary rectors, high-ranking priests did so in view of protecting their career aspirations. McCarrick was powerful; it wasn’t convenient to get in the way of him.

Yet Jesus does not condone ambition at all: he opposes with great severity the search for power, fame, glory and ecclesiastical titles (“do not call anyone father on earth”). Benedict XVI and Pope Francis have been preaching against careerism and clericalism for years, but with what results? Or better, what practical resolutions have been taken?

How can a church immersed for centuries in the anti-evangelical practice of honours, careers, titles (holiness, eminence, excellence, monsignor) and all the attached pomp have the antibodies to reject corruption, clericalism and careerism? Wouldn’t it be about time to change this shameful trend once and for all? As long as this fashionable careerist system is an integral part of the church, there is little point in asking for the conversion of the conscience. Titles, honours, career procedures and consortiums are the lymph of careerism and clericalism: when will they be eliminated?

Careerism and corruption often go together. In 2000, New York Cardinal John O’Connor asked the pope not to promote McCarrick. The latter perjured that he was innocent, deceiving the pope with a letter which, however, was addressed, rather unorthodoxly, to his personal secretary. McCarrick relied on an amicable report and other correspondence mentioned in the lying letter but not delivered to the drafters of the report.

There is something dark in this crucial passage, a passage that led to catastrophic consequences. There is perjury (Jesus says never to swear!) and an unjustifiable deviation from the principle of prudence. We are also informed that, every year at Christmas, McCarrick gave gifts to senior Vatican clergymen and that this practice lasted until 2017. The report does not say who they are. (We know this, however, from a Washington Post investigation of December 27, 2019, which also reports the amount of the transferred sums.)

Is this also normal? I wouldn’t say so, given that the McCarrick case had been on various Vatican tables for a couple of decades at least. I hardly believe that Vatican high officials are indigent and need these gifts. I may believe that most of them would devolve the money to charities, yet it would be far better if the offerings had gone directly to the charities. It is to be hoped that such a harmful practice, which smacks of attempted corruption, will be abolished. In most governing bodies, law punishes these practices.

The report by the Secretariat of State may represent a turning point in Vatican practices. Papal secrecy on relevant material has been lifted. Dishonourable practices and behaviours are candidly admitted. But I would avoid the triumphalism that seems to emerge here and there: finally, a cleaning has been made, the pope has chased away the bad guys, the truth has triumphed in the end. It is not so. There are still too many things that are not clear at all. Some protagonists have not said all they know, or they just said nothing. This report must be the beginning of good practices of transparency.

There are still too many grave questions that tarnish the credibility of the Catholic Church. Scandals demand justice and have never been clarified. One scandal above all — not the only one, but the most serious — concerns the terrible and hallucinating crimes committed by the founder of the Legionaries of Christ, Marcial Maciel.

What do I have to do with the Mexican Maciel? Nothing. Except that I remember well that in the months I spent in Mexico in 2004 and 2005, almost every day we read testimonies of criminal abuses committed by Maciel, testimonies that turned out to be true, and not even among the most infamous. But the Vatican — and the elderly pope — defended, indeed honoured him. In the face of the enormity of the charges, Rome should had applied the principle of prudence. Rome did not. We simple Christians learned the importance of the first cardinal virtue as children while studying catechism.

Like McCarrick, Maciel also deceived John Paul II. By faith, I want to believe in the good faith of a pope declared a saint. Yet, until Benedict XVI, no one stopped Maciel, who was supported and covered by two cardinal secretaries: Stanisław Dziwisz and Angelo Sodano (the latter responsible for the insufferable compliance of John Paul II towards the bloody dictator Augusto Pinochet). I think that out of a sense of justice, and for the honour of John Paul II, the two cardinals have the duty to tell the people of God what happened, how so much havoc could have happened. The community of believers deserves better than their silence.

It is not true, as it is superficially said, that the church of the past was more corrupt than the current one. The McCarrick and Maciel cases (they are not the only ones, unfortunately) tell another story. An investigation into Marcial Maciel, the scandal of scandals, is a very necessary step for the good of the Church. Reforms, acts of cleansing, transparency and justice are very necessary before the people of God and for the credibility of the proclamation of the gospel.

Father Gianni Criveller of the Pontifical Institute for Foreign Missions is dean of studies and a teacher at PIME International Missionary School of Theology in Milan, Italy. He taught in Greater China for 27 years and is a lecturer in mission theology and the history of Christianity in China at the Holy Spirit Seminary College of Philosophy and Theology in Hong Kong.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official editorial position of UCA News.

With thanks to the Union of Catholic Asian (UCA) News and Fr Gianni Criveller, where this article originally appeared.