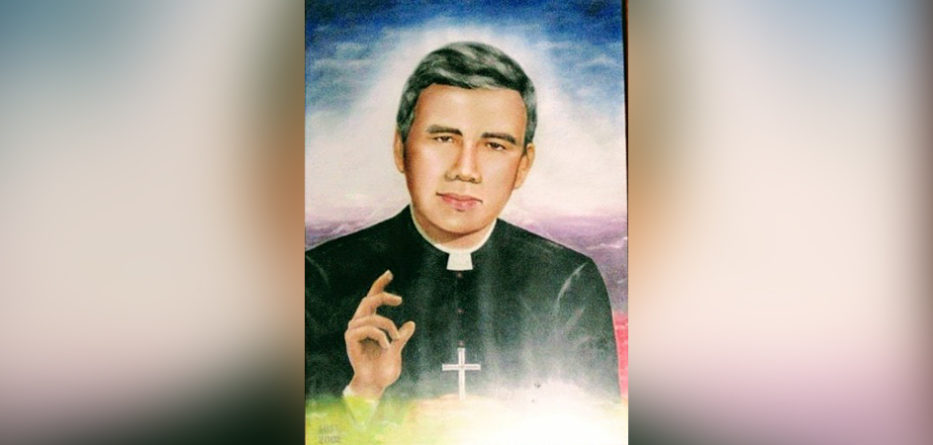

A couple of weeks ago, the Salvadoran bishops announced that four martyrs from El Salvador—two priests and two laymen—will be beatified on January 22 next year in the San Salvador Cathedral: Jesuit Fr. Rutilio Grande, Franciscan Fr. Cosme Spessotto, 70-year-old sacristan Manuel Solórzano, and teenager Nelson Rutilio Lemus.

English-speaking audiences might be most familiar with Fr. Grande, Solórzano, and Lemus from the 1989 movie Romero, a biographical film about another Salvadoran saint, Archbishop Oscar Romero, starring Raul Julia. The film depicts their murder as they traveled by car on March 12, 1977, on their way to take part in a novena dedicated to the upcoming feast of St Joseph. Some men in another car pulled up alongside theirs and riddled them with bullets. Three children riding in the backseat survived.

In her biography of Fr. Grande, journalist Rhina Guidos suggests that this was the moment that changed Archbishop Romero, and set him on a path ultimately leading to his own martyrdom. She recounts the Archbishop’s response to their death:

“The archbishop who was normally so composed cried inconsolably after learning of the death of Father Rutilio. When Archbishop Oscar Romero arrived at the parish of Our Lord of Mercy in Aguilares, where the bodies of Rutilio, Manuel Solórzano, and Nelson Rutilio Lemus had been taken after the killings, he would look at them spread out on a table. Romero would look particularly at Father Rutilio’s body and ask, ‘What have they done to you?’ Father Jon Cortina later recalled. ‘He was astounded at the great barbarity that had taken place.’”[1]

She also wrote about how Fr. Grande’s murder immediately changed Romero, and giving him greater focus and a stronger sense of urgency in standing up for the poor of his archdiocese:

“Father Rutilio’s brutal killing almost instantly changed Archbishop Oscar Romero that day. Before becoming archbishop of San Salvador, Romero had been reluctant to get involved in addressing El Salvador’s growing social problems and how they disproportionately affected the poor in the areas of land reform, housing, hunger, education, health care, and so forth. He also had made it known in church circles that he didn’t want other members of the clergy to do so either.

“With the killing of Father Rutilio, however, Archbishop Romero had to confront the issues head-on because the Jesuit, who was a close friend, had died precisely because he was calling attention to them.”[2]

These two men are intrinsically linked, both through their friendship and their ministry to the Salvadoran people, which led to their deaths as holy martyrs. It is also fitting that Fr. Grande will be accompanied in beatification by two members of the laity who not only assisted him in his service to the people of God but gave their lives for their people as well. This interconnectedness—between bishop and priest, pastor and people—is a living example of Pope Francis’s oft-repeated phrase, “No one is saved alone.”

Pope Francis spoke of this connectedness between Romero, Grande, and the people in a 2015 meeting with pilgrims from El Salvador, saying, “Archbishop Romero’s witness has been added to that of other brothers and sisters, such as Fr Rutilio Grande, who, not fearing to lose their life, have won it and have been constituted intercessors of their people before the Living God, who lives forever and ever, and who has in his hands the keys of death and Hades (cf. Rev 1:18).”

And in Panama in 2019, he spoke about his fellow Jesuit during a meeting with local members of the Society:

“Rutilio is very dear to me. At the entrance to my room there is a frame containing a piece of cloth with Romero’s blood and notes from a catechesis by Rutilio. I was a devotee of Rutilio even before coming to know Romero better. When I was in Argentina, his life influenced me, his death touched me. Well informed people tell me that the declaration of martyrdom is going well. And this is an honor… men of this kind… Rutilio, moreover, was the prophet. He converted Romero.”

So how does Fr. Cosma Spessotto fit into this group?

Unlike Romero and the three men with whom he will be beatified, Fr. Spessotto was not a native of El Salvador. He was a Franciscan friar from Trevino, Italy, who arrived in El Salvador after the 1948 expulsion of foreign missionaries made it impossible for him to serve in China. According to the Franciscans’ website, “He was a faithful witness to the Gospel in a context marked by profound social injustice and torn apart by bloody feuds. He called people, by word and works of mercy, to peace, dialogue and respect for life. His work of reconciliation brought him hatred from Christ’s enemies, who killed him at the hands of assassins, while he was at the altar after celebrating Mass in the parish church of San Juan Nonualco.” He was killed on June 14, 1980—less than three months after Romero’s death. Like St. Oscar, he was killed in a church sanctuary. Like Fr. Rutilio, he was an advocate for social justice and a servant leader to his people. And like all these men, he gave the ultimate sacrifice for his faithful witness.

I would like to close with a reflection from my friend Carlos Colorado, who has written extensively about the Church in El Salvador and St. Oscar Romero (including for Where Peter Is). I asked him if he would be willing to share his thoughts on the news of the upcoming beatification:

“My first reaction to the news of the joint beatification of Grande, Spessottto, Solorzano, and Lemus is that this is the Church of St. Oscar Romero on display. I don’t just mean that these are his contemporaries or that they were martyred in the same historical circumstances. I mean that these four—a Jesuit, a Franciscan, an elderly sacristan, and a young bell ringer—embody the vision of the Church that Romero had. “The Church of Easter,” Romero called it, meaning that in a time of bitter dictatorship and repression, this Church was giving people hope and a sense that God was with them.

“It struck me that the fact that they are being beatified as a group of martyrs means this beatification—when it is celebrated in the atrium of the San Salvador Cathedral—will resemble the ceremonies in Rome, where candidates from diverse walks of life are presented together in the atrium of St. Peter’s. Here, there is that diversity—and I would not overlook Manuel Solorzano and Nelson Lemus, because they are being recognized as martyrs as well. They make me think of the intergenerational “bridge” that Pope Francis frequently proposes: the old and the young, together, as Church. As people.

“Finally, I think of that setting: the atrium of the San Salvador Cathedral. Of course, that’s where Rutilio, Manuel, and Nelson were sent off, together, in Archbishop Romero’s liturgically groundbreaking “Single Mass.” It’s the same stage where many of Romero’s priests—and Romero himself—were mourned in open-air masses. It’s the stage of a 1979 massacre on the steps, and of the stampede during Romero’s funeral in 1980. It is a truly historic place and the presider will be one of their contemporaries, Cardinal Gregorio Rosa Chavez. He is a historic choice for this historic stage. It bodes to be a momentous liturgy.”

Mike Lewis is a writer and graphic designer from Maryland, having worked for many years in Catholic publishing. He’s a husband, father of four, and a lifelong Catholic. He’s active in his parish and community. He is the founding managing editor for Where Peter Is.

With thanks to Where Peter Is and Mike Lewis, where this article originally appeared.

Notes:

[1] Guidos, Rhina. Rutilio Grande (People of God) (p. 62). Liturgical Press. Kindle Edition.

[2] Ibid. p. 2.