Third Sunday of Lent

Readings: Exodus 3:1-8, 13-15; Psalm 102(103):1-4, 6-8, 11; 1 Corinthians 10:1-6, 10-12; Luke 13:1-9

Sunday 20 March 2022

Breaking Open the Word

In moments of suffering and misfortune, people often question whether they have done something to deserve their suffering, or they question whether God is punishing them.

When some people told Jesus about the Galileans whose blood had been mingled with other sacrifices, it was as if they were questioning whether the Galileans had actually deserved the suffering and the evil that had fallen upon them. Had they done something wrong that they should meet such a terrible end, as if their terrible end were somehow a just and fair punishment from God. But Jesus, aware of their line of thinking, responds by saying that the Galileans who suffered were no worse sinners than all the other Galileans: “Do you suppose these Galileans who suffered like that were greater sinners than any other Galileans? They were not, I tell you.”

In other words, the victims of violence, abuse, and other crime, do not deserve the suffering and evil that comes their way. Sure, if someone is a violent person and lives a violent lifestyle, then it might come as no surprise if they themselves eventually meet a violent end, especially if they have made many enemies along the way. All who live by the sword die by the sword, so to speak (Mt 26:52). But Jesus reminds us that just because someone has suffered at the hands of another person, it does not mean that they deserve it. We must never think that they deserve it, or if we are the ones suffering at the hands of another, we must never think that we deserve it.

Jesus goes on to point out that the 18 people who were killed when the tower of Siloam collapsed and fell upon them were no more guilty than everyone else living in Jerusalem. Throughout human history, accidents and natural disasters have often been seen as a punishment from the gods, but Jesus is making the point that the victims of accidents and natural disasters are not worse people than those still living, and so, we must never think that the victims deserved the suffering that came their way, and we must never think that they were being singled out by God for punishment.

In both the above cases, Jesus concludes by saying that, “Unless you repent you will all perish as they did.” When we hear of victims of violence, when we hear about the unexpected loss of life caused by accidents and natural disasters, when we hear of suffering or when we ourselves experience suffering, it is a reminder to us of our own mortality, a reminder to us that life is short and that we do not know the day or the hour of our own death (cf. Mt 24:44; 25:13; Lk 12:16–21; 12:35–48). And therefore, it is an opportunity for us to repent and change our ways, helping us to cleanse our hearts. It is an opportunity for us to question what is truly important in life, helping us to let go of the things that are genuinely not important, so that we might be ready for the day when we are called to stand before God.

The Gospel ends with a short parable in which the fig tree is given another opportunity to bear fruit. It is a reminder to us that it is never too late to repent and change; God is willing to give us another chance to begin again.

Fr Antony Jukes OFM

Artwork Spotlight for personal reflection

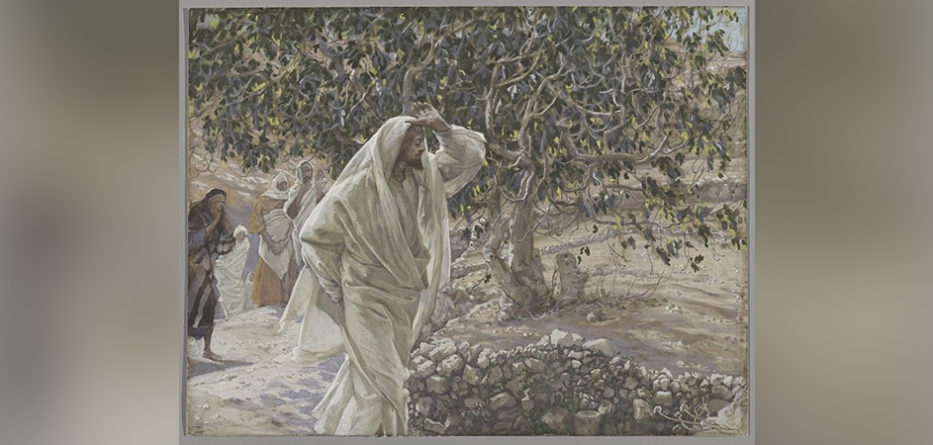

The Accursed Fig Tree (1886–1894) – Jacques Joseph Tissot (1836–1902)

The Accursed Fig Tree (1886–1894). Opaque watercolor over graphite on gray wove paper, 21.3 x 27.9 cm. Brooklyn Museum, New York, USA.

Jacques Joseph Tissot was born to a middle-class family and initially studied art in Paris. His early paintings are mainly historical. His life was changed by the Franco-Prussian War of 1874. Following the French defeat, he decided to move to London. He needed money quickly and started to paint highly accomplished pictures of London society. They were an instant success with the buying public, but not with the critics who saw them as “vulgar”. But they showed dazzling technique.

He fell in love, and his mistress actually became his muse, appearing in many of his pictures. Tissot never got over her death six years later, and moved back to Paris. He devoted the rest of his life to painting religious scenes, even visiting the Middle East twice to find genuine backgrounds for his paintings. He died in 1902.

The fig tree appears in the Gospels of Mark and Matthew in the same context. Jesus curses a tree he comes upon for bearing no fruit. Both evangelists combine the event with the cleansing of the Temple. In the Scriptures, the people of Israel were sometimes represented as figs on a fig tree (Jr 24), and the prophet Micah pictured the age of the Messiah as when a man could sit under his fig tree without fear (Mi 4:4). This is exactly what Nathaniel was doing when Jesus called him (Jn 1:48). But Jesus’ cursing of the fig tree is symbolically directed towards the Jews who would not accept Jesus as King. The implied message was that the Temple, too, would wither like the fig tree because it failed to produce the fruits of righteousness.

Jesus’ actions in cleansing the Temple and cursing the fig tree might seem like the image of a bitter man, but Luke sees it differently. They were the actions of a man with a broken heart. “As he drew near and came in sight of the city he shed tears over it and said, ‘If you had only recognised the way to peace!’” (Lk 19:41–42). And so, Luke turns the occasion of the cursing of the fig tree into a parable with a universal meaning.

The fig tree occupied a specially favoured position. Soil was so shallow and poor in Palestine that trees were grown wherever good soil could be found. This tree had more than the average chance—it was in a vineyard! It would have had constant care. In other parables, we are reminded that the vineyard owner is God who will rightly judge us according to the opportunities given us. The gardener represents Jesus himself who feeds his people and gives them living water. The three year period is significant because for three years, John the Baptist and Jesus had been preaching the message of repentance. John had actually said, “Even now the axe is being laid to the root of the trees, so that any tree failing to produce good fruit will be cut down and thrown on the fire” (Lk 3:9).

And the parable teaches that nothing which only takes out can survive. The fig tree was drawing strength and sustenance from the soil, and in return was giving nothing back. That was its sin. We are all in debt to life. We came into it at the peril of someone else’s—our mother’s—and we would never have survived without the care of those who loved us. We have inherited a beautiful world, as Pope Francis continually reminds us, and we have been given the gift of the faith through no merit of our own. We have the duty of handing on our civilization better than we found it. “Ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country,” still rings in our ears from John F. Kennedy.

The Jews were offended by the very notion that they needed repentance (the word actually means “to think again”.) They had it all! They were the chosen vineyard. The Temple’s facade was adorned with a giant cluster of golden grapes representing the nation. But they had turned the Law of a loving God into legalism, and actually thought God owed them something. “I thank you, God, that I am not grasping, unjust, adulterous like the rest of mankind” (Lk 18:11) said the Pharisee in the Temple, talking to himself rather than to God.

Jesus, the divine Gardener, pleads for a little more time, and the gracious Lord of the vineyard responds in patience. The Gospel is, of course, the Gospel of the second chance (St Peter would certainly agree with that!). But the lesson for us is that borrowed time is not permanent. Christ stands at the door and knocks (Rv 3:20), but he doesn’t knock forever. “Seek the Lord while he may be found; call on him while he is near,” implores the prophet Isaiah (Is 55:6).

Mgr Graham Schmitzer

Fr Antony Jukes OFM was raised in a Catholic family in Chingford, East London (the second of six children.) He was an altar server at his parish for many years, but found himself drifting from his faith during his years at university. After completing his studies, he worked as a trainee-chartered accountant in central London. It was on a pilgrimage to the shrine of Our Lady of Lourdes (France) that led him to rediscover his love for his Catholic faith and to question his vocation. His devotion to St Antony of Padua, after whom he was named, and his love for St Francis of Assisi, led him to join the Franciscan Order of Friars Minor in 2002. He studied philosophy and theology at what was the Franciscan International Study Centre in Canterbury, England, before being ordained a priest in 2009. Having served in a parish and in a youth retreat centre, Fr Antony is now the novice director at the international novitiate community in Killarney, Ireland.

Mgr Graham Schmitzer is a retired parish priest in the Diocese of Wollongong. He was ordained in 1969 and has served in the parishes of Campbelltown, Gwynneville, Unanderra, Wollongong, Albion Park, and Corrimal. He was also chancellor and secretary to Bishop William Murray for 13 years. He grew up in Port Macquarie and was educated by the Sisters of St Joseph of Lochinvar, completing his leaving certificate at Wauchope High School. For two years he worked for the Department of Attorney General and Justice before entering St Columba’s College, Springwood, in 1962. Fr Graham loves travelling and has visited many of the major art galleries in Europe.

With thanks to the Diocese of Wollongong, who have supplied these weekly Lenten 2022 reflections from their publication, Remember – Lenten Program 2022.