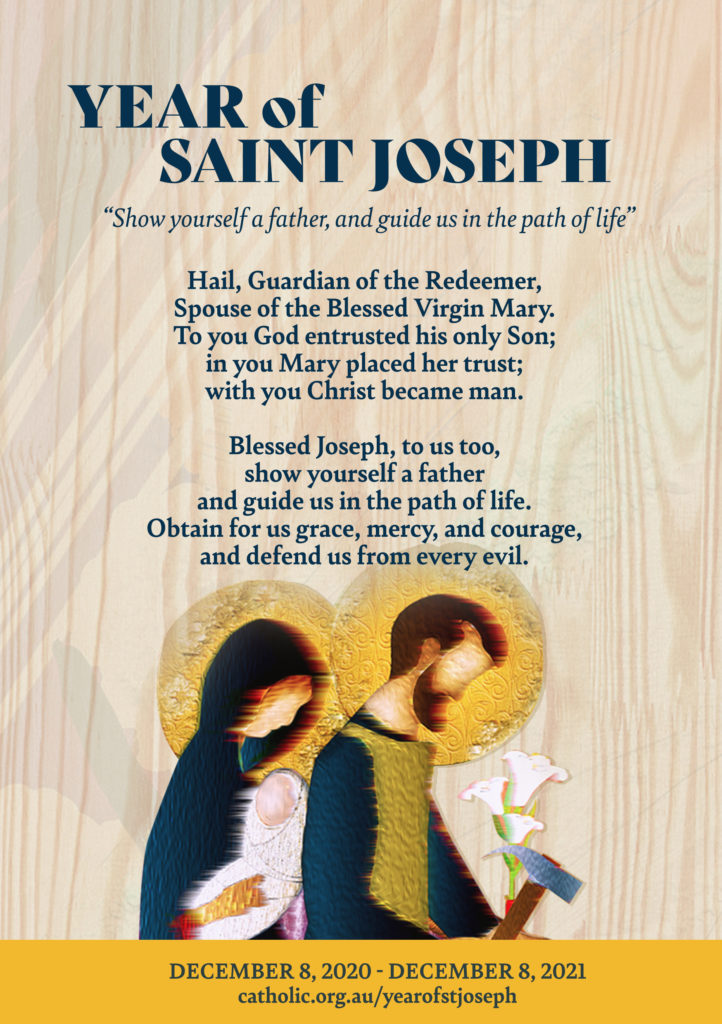

On 8 December 2020, Pope Francis published an Apostolic Letter Patris corde (With a Father’s Heart), commemorating the 150th anniversary of the declaration of Saint Joseph as Patron of the Universal Church. To mark the occasion, the Holy Father has proclaimed a “Year of St Joseph”, running from December 8, 2020 to December 8, 2021.

The Australian Catholic Bishops Conference, to commemorate the Year of St Joseph, will be releasing a reflection on the various aspects of St Joseph’s life and character each month throughout 2021.

St Joseph — “A Just Man”

Generally, when the saints are presented to us as models for imitation, we are shown how they embodied some particular virtue shown in them.

In the case of St Joseph, we are told that he is “a just man” in the context of his deciding to put Mary away privately or divorce her informally. Ever since the early Church, people have wondered why this particular action makes St Joseph just.

One suggestion is that he knew Mary’s chastity, and wished to conceal in silence what he did not understand. But if Mary wasn’t really at fault at all and Joseph knew this, then she would be treated unjustly by being put away, quietly or not. On the other hand, if she is indeed guilty of adultery, concealment of the sin would seem to be participation in her injustice.

The text suggests, rather, that Joseph really was ignorant of what the reality was and the guilt or innocence of Mary. And his justice in this situation is that he does not expose her to a public trial for a private sin that, in all likelihood, she might not have been guilty of. At the same time, he also does not want to prejudge the issue of guilt. So he decides to balance what the law requires of him with mercy towards her.

Joseph’s example helps us as we work out how to live justice in our day-to-day lives.

Often the Christian imperative to mercy is misinterpreted, so as to suggest that in all situations, it is the only possible Christian response to any injuries that one has suffered, particularly private injuries. In particular, we do this in relation to families and often in the confessional. But mercy needs also to satisfy the demands of justice and restoring the relationship and the order damaged by the injury. And behind those abstractions of “relationship” and “order” lies human suffering in all its painful reality. To ignore this is itself a denial of mercy towards someone who has suffered injustice.

On the other hand, justice, if it is to be justice, should be marked by the mercy which recognises the humanity and dignity of both the person who committed the injury and the person who suffered. It should leave the road open to someone’s innocence or their conversion, as well as account for the limitedness of our knowledge. Not to allow for this is to be unjust in the sense of not giving someone their due.

Thus, mercy and justice, far from being opposed to each other, actually undergird and enable each other.

The Scriptures call St Joseph ‘just’ after showing us a situation which he initially misread because of his limited understanding of what was happening. This should encourage us not to set aside the quest for justice as impossible in view of our limited knowledge or our own sinfulness or the sinfulness of the world at large. It should lead us not to set mercy in opposition to justice to the detriment of both, but trust that if we aim for it in union with God, we too can attain it through his mercy and his grace.

Fr Robert Krishna OP is a Dominican priest and chaplain to Monash University.

With thanks to the ACBC.