December 8 marks the 150th anniversary of the opening of the First Vatican Council. This is the final article in a series of articles on the Council, its key moments and its legacy. The first article was published here. The second article was published here.

Full in the panting heart of Rome

Beneath the apostle’s crowning dome.

From pilgrim’s lips that kiss the ground,

Breathes in all tongues one only sound —

God bless our Pope, the great, the good!

In this hymn, Nicholas Patrick Wiseman, the first Cardinal Archbishop of Westminster, captured the surge in devotion to the Pope that became a feature of Catholic spirituality in the 19th century and reached a crescendo during the reign of Pope Pius IX (1846-1878).

By the time the First Vatican Council opened on December 8, 1869, the papacy had survived the crisis of the French Revolution in the late 18th century and the humiliation of Napoleon’s invasions of Rome that led to the capture and imprisonment of Pope Pius VI and later Pope Pius VII.

Buffeted by the challenges of the Enlightenment, the unification of the Italian peninsula and virulent anti-clericalism, Pope Pius IX was devastated when the last remnant of the Papal States – the city of Rome – was incorporated into the new kingdom of Italy in September 1870.

Nevertheless, with the benefit of hindsight, his loss of temporal power was more than offset by the gain in spiritual authority. The political crises did, however, leave their mark.

Pius issued the Syllabus of Errors in 1864, a document that was reactionary in tone, famously decrying among other “errors” the proposition that “the Roman Pontiff can and should reconcile himself with progress, liberalism and recent civilisation”.

The Sydney Morning Herald published a letter from “A Catholic” (subsequently revealed to be W.A. Duncan, a former organist at the cathedral in Brisbane) that railed against two tendencies: uncritical acceptance of the Syllabus on one hand and complete denunciation of it on the other.

Duncan could see value in some of the Pope’s strictures, but he stressed that “Catholics are not obliged to receive political fallacies even from a Pope, and even those among us who think the Pope infallible in his religious teaching may, if they please, think him a very bad authority on subjects of political government.”

Duncan concluded with the hope that Pius IX would eventually develop a more positive relationship with modern civilisation. One step in that direction occurred early in his pontificate when he gave permission for railways to be constructed in the Papal States; they had been banned by his predecessor.

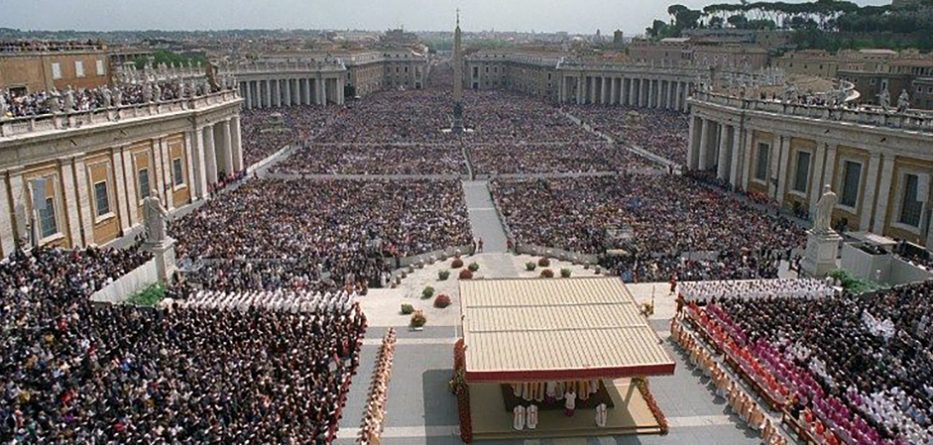

Pius also dramatically increased the number of papal audiences. By steam ship and steam train, countless pilgrims travelled to Rome and encountered a Pope who was, according to most reports, a warm and caring pastor of souls. He was the first Pope to be photographed and mass-produced prints were hung in Catholic homes around the world.

Australia’s first canonised saint, Mary MacKillop, made the long voyage from Australia in 1873, less than two years after her excommunication by Bishop Sheil in Adelaide in 1871. In a letter to her mother, Mary recounted her meeting with Pius IX: “What he said and how he said it when he knew I was the Excommunicated one, are things too sacred to be spoken of—but he let me see that the Pope has a Father’s heart.”

After another meeting a few weeks later, Mary noted in her diary that the pope was “so kind”.

The late Patrick O’Farrell, in his history of the Catholic Church in Australia, asserted that “to most Australian Catholics, the papacy, its politics and pronouncements seemed remote and irreverent.”

Belying this judgement is the media coverage in country and city newspapers during Pius’s lifetime – now much more accessible than it was when O’Farrell was writing The Catholic Church and Community, as a result of the National Library of Australia’s digitalisation project.

Australians were well informed about the debates going on behind the scenes at the First Vatican Council. The Bendigo Advertiser observed in February 1870 that “the apple of discord has been thrown down, and we may expect what are known as stormy discussions”. The Gympie Times and Mary River Mining Gazette offered its readers two months a translation of a letter to the Pope from a group of German-speaking bishops protesting the proposed decree.

The Protestant Standard predictably mocked “infallible nonsense”, while The Australasian reported that the bishops had voted 400 in favour of the infallibility of the pope and 88 against, with 62 “conditional votes”. It was not stated, but this was a preliminary vote on the draft decree held on July 13, 1870, with 451 the real number of “ayes”.

The Melbourne Catholic paper, The Advocate, recognised that not all Catholics embraced the notion of infallibility, but was confident that the final decision of the Council would be accepted without demure.

After Pius’s death on February 7, 1878, The Sydney Morning Herald commented: “No one who has lived during the last half century has done more, and few have done so much, to attract or to repel mankind.”

In a time of heightened sectarian tension, exacerbated by the withdrawal of government aid from Catholic schools, there would have been some Catholics embarrassed by the proclamation of the decree on papal infallibility, even in its final, nuanced form, while others clearly embraced it. For all, it was a reminder of the distinctive nature of the central government of the Roman Catholic Church.

Pride in a profound link with the Bishop of Rome went beyond doctrine and found exuberant expression in Catholic piety. An example of this from the early 20th century can be found in the diary of a young Melbourne seminarian training for the priesthood in Rome.

After attending a Eucharist celebrated by Pope Benedict XV in 1919, Matthew Beovich, the future Archbishop of Adelaide, exulted: “There in the stillness we, eighty favoured ones, assisted at the Mass of the Father of Christendom, the ruler of 300 million loving hearts . . . before our eyes God and His Vicar were speaking, even as He and Moses spoke on Mount Sinai.”

Back in the immediate aftermath of the First Vatican Council, a report in The Advocate in 1871 noted the increasing popularity of Cardinal Wiseman’s “exquisite” hymn, Full in the Panting Heart of Rome. At school and in his local parish, Beovich doubtless sang it many times.

Dr Josephine Laffin is a senior lecturer in Church history at the Australian Catholic University in Adelaide.

With thanks to the ACBC.