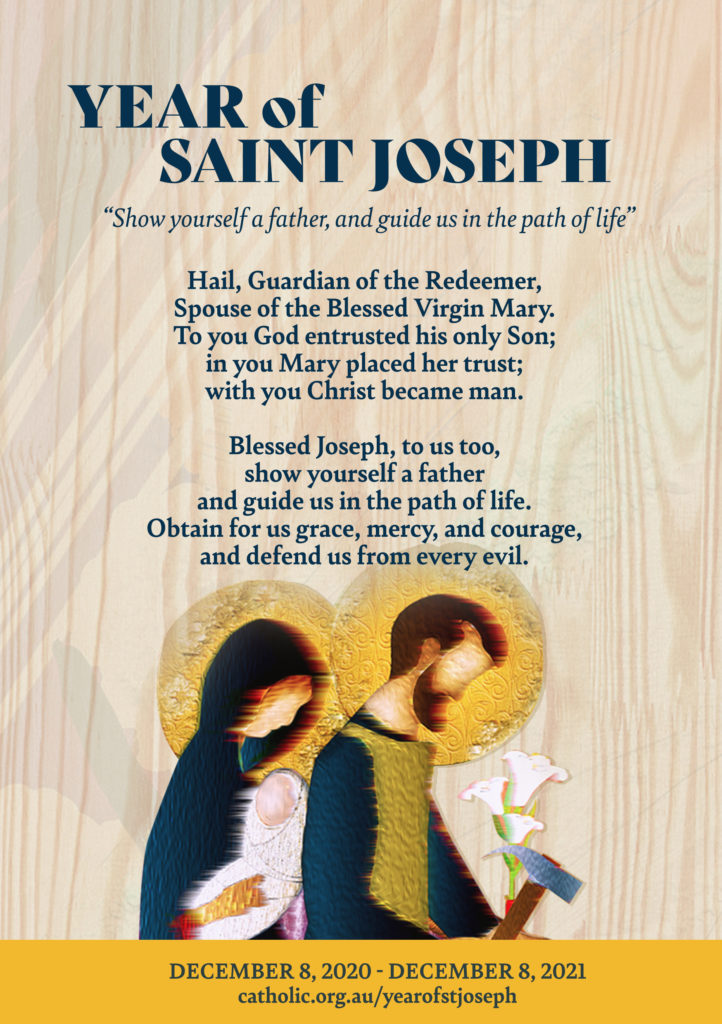

On 8 December 20202, Pope Francis published an Apostolic Letter Patris corde (With a Father’s Heart), commemorating the 150th anniversary of the declaration of Saint Joseph as Patron of the Universal Church. To mark the occasion, the Holy Father has proclaimed a “Year of St Joseph”, running from December 8, 2020 to December 8, 2021.

The Australian Bishops Conference, to commemorate the Year of St Joseph, will be releasing a reflection on the various aspects of St Joseph’s life and character each month throughout 2021.

The Gospels of Matthew and Luke both have genealogies of Jesus Christ. They are not identical, in part because each seeks to make a different theological point. Each in its different way traces the lineage of Joseph.

The reasons for this are more Christological than biological. The fundamental promise of the Old Testament is the promise to Abraham and his descendants – a promise of life bigger than death, symbolised by offspring and patrimonial land, which were the symbols of life beyond death in the cultures that produced the Bible.

The question through time was: How is this blessing to be mediated in the life of the People of God? Different answers were given at different times. The God-given institutions were seen as mediating the Abrahamic blessing – the monarchy, the prophetic movement, the priesthood – depending upon which was in the ascendant at any given time.

Ancient Israel begins as a loose tribal federation with no centralised government. That changes once Israel faces the new kind of military threat represented by the Philistines. They were a formidable foe, culturally more advanced and with the latest in high-tech weaponry; and they seemed to have the tribes of Israel surrounded. The new peril demanded a new kind of military and political unity; and that’s when you first hear in the Bible the cry for a king.

The decision to have an anointed king, a Messiah, came at the end of a slow and painful process, as we see in 1 Samuel 8-12. The theological problem was that God was supposed to be the only king of Israel; and any king on earth would seem to rival or reject the kingship of God.

A compromise was eventually reached to satisfy everyone militarily, politically and theologically. There would be a king – but a different kind of king. He would be as much subject to God’s law as anyone else in the community. Unlike the rulers of Egypt or Mesopotamia, he would be one of his brothers and sisters, like them a slave set free.

The first king, Saul, was deposed by the prophet Samuel because he had disobeyed God. He was succeeded by David, chosen by Samuel at a young age. David came to the throne in about 1000 BC and reigned for something like 40 years. It was a time when, unusually, both the Egyptian and Mesopotamian empires were weak at the same time. Usually one was strong and the other weak, with the strong becoming the dominant power in the region.

David took advantage of the situation to carve out a mini-empire. His military success was seen as a potent sign of God’s blessing upon him and the people, as was his success in uniting the 12 tribes in a single kingdom with its united capital in Jerusalem. Eventually, there came through the prophet Nathan a divine promise that the House of David would last forever. In other words, the Abrahamic blessing would be mediated eternally through the Davidic dynasty.

This was fine until the Babylonian Exile in 587 BC, when the Davidic dynasty disappeared into the black hole of history because – the prophets said – the kings had disobeyed God’s law. What then of God’s promise of an eternal dynasty? Was God perhaps powerless or unreliable?

In order to save their faith in God’s absolute fidelity to the promise, ancient Israel gave the promise to David and his descendants an eschatological twist. In the End-Time, they said, an ideal Davidic king, a Messiah, would appear to usher in the reign of God. He would finally mediate to the People of God the fullness of the blessing promised to Abraham and his descendants. This is what Judaism meant when it said that the Messiah would come from the House of David.

Christianity came to see in Jesus crucified and risen the ideal Davidic king mediating a life bigger than death, most especially through his resurrection from the dead. He was the long-awaited Messiah, mediating the fullness of God’s blessing as priest, prophet and king.

The Gospels, therefore, are keen to stress Jesus’ connection to David in order to make that point. They recognise that Joseph wasn’t the biological father of Jesus, which is why in later tradition Davidic descent was often attributed to Mary as well as Joseph.

The New Testament says nothing of this – though it’s not impossible, given the custom of bridegrooms choosing a bride from within their own tribe. But again the point is less biological than Christological. It is more about who Jesus is than who Joseph is, more about what God does through Jesus than what God does through Joseph.

It is often said that Mariology is a form of Christology, and the same is true of Josephology.

Mark Coleridge is the Archbishop of Brisbane and president of the Australian Catholic Bishops Conference.

With thanks to the ACBC.