December 25: Christmas Day

The ways in which we Australians celebrate Christmas are full of contrasts. They are both cultural and countercultural. The cultural aspect can be is seen in the spruiking, advertising and all the other ways money is transferred from families to business. The turkeys, the Christmas trees, the Christmas-wrapped grog, chocolates, mince pies, and the toys, clothes and devices also gift-wrapped, and the Cricket on Boxing Day are about the economy and consumption.

The countercultural aspect of Christmas lies in what people do – relax instead of work, eat and drink at leisure, spend time with their families, visit relatives and friend and take holidays, and often think of people who are doing it hard in hospital, nursing homes and on the streets. For people who have lost family, have no money or are homeless, Christmas is totally countercultural. It is a time when the joy, gift -giving and celebration can deepen sadness and isolation and stir memories of past hopes trampled on.

The Christian story of Jesus’ birth reinforces the countercultural aspects of the Australian Christmas. That is not surprising. In the first Christmas God becomes involved in the minute details of human life. In doing so he shows how precious is the human world in all its relationships. Nothing loved by God is without value. No baby is just a baby. This means that the customs and practices of our Australian Christmas should not be dismissed simply as a corrupted and so inferior version of the Christian celebration. They should be appreciated in their own right. To get in touch with people at Christmas, even through online Santa cards, to gather with the extended family, to take time off work, to soften for an hour or so the hard edges of workplace relationships and to donate to charities, all embody the values that are affirmed and grounded in the story of Jesus’ birth.

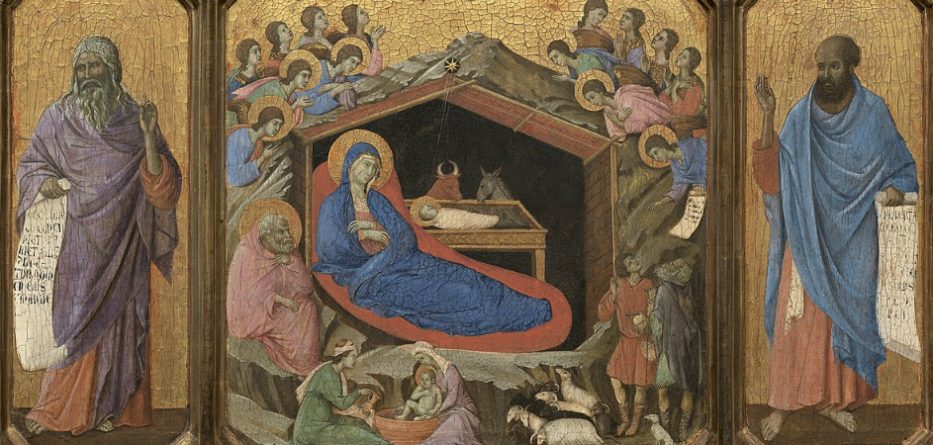

The Christian story, however, has a depth that challenges all our practices. In it God’s coming among us takes place in solidarity with the most hassled people: a heavily pregnant woman compelled to travel for tax purposes, a couple homeless when the baby is due, people sleeping out in the fields, ostracised shepherds, and refugees forced to flee for their lives.

The celebration of Christmas encourages all people of good will, whatever our religious beliefs, to walk for a time in solidarity with people at the bottom of the pile, to take time to dream of who we are invited to be, and to reflect on what kind of a society we want.

The inn with no room, the people in the parks, the threat of Herod, the disreputable shepherds, the refugees in Egypt, the rumour of angels and the realities of refugee life are the characters in the Christmas story. Their counterparts are found in our personal and public stories today. They make a claim on us all the year round.

Fr Andrew Hamilton SJ writes for Jesuit Communications and Jesuit Social Services.