Homily for the 30th Sunday in Ordinary Time

26 October 2024

Readings: Jeremiah 31:7-9; Psalm 125; Hebrews 5:1-6; Mark 10:46-52

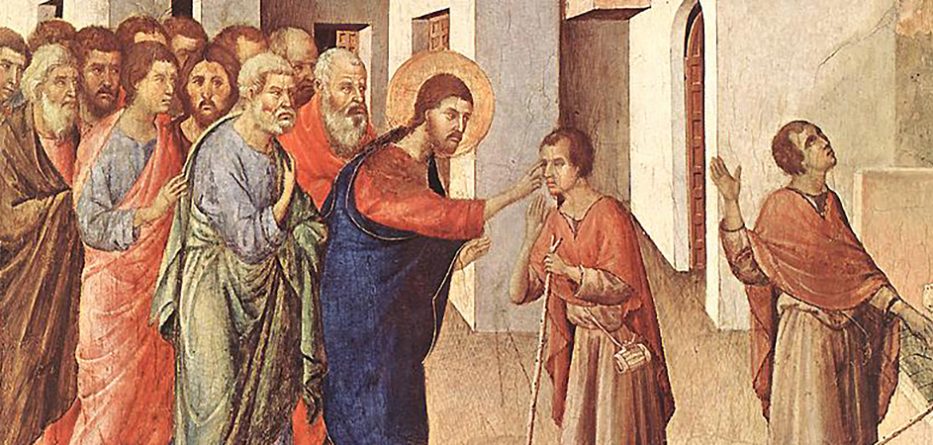

In today’s gospel, the blind man Bartimaeus calls out to Jesus for healing, for liberation. Those around Jesus try to quieten Bartimaeus. They want him silenced. But Jesus hears him and cures him. Bartimaeus then follows Jesus along the way. It’s a familiar story: religious authorities wanting to silence those who are poor, those on the peripheries. And then wanting to silence those who stand with the poor and those who speak up for them.

Listen at https://soundcloud.com/frank-brennan-6/homily-271024

This past week we celebrated, though without much fanfare, the feast of St John Paul who was our pope from 1978 until 2005. His feast day is 22 October, that being the date in 1978 on which he commenced his Petrine ministry. The week ended with the death of the Peruvian Dominican priest Gustavo Gutiérrez, the 96 year old liberation theologian who published his most famous book A Theology of Liberation in 1971. In the early years of John Paul’s pontificate, there were those around the pope demanding that the likes of Gutiérrez be quietened. Vatican officials wanted these liberation theologians to be silenced. In the introduction to his A Theology of Liberation, Gutiérrez wrote:

‘I pay special attention in this work to the critical function of theology with respect to the presence and activity of humankind in history. The most important instance of this presence in our times, especially in underdeveloped and oppressed countries, is the struggle to construct a just and fraternal society, where persons can live with dignity and be the agents of their own destiny. It is my opinion that the term development does not well express these profound aspirations. Liberation, on the other hand, seems to express them better. Moreover in another way the notion of liberation is more exact and all embracing: it emphasises that human beings transform themselves by conquering their liberty throughout their existence and their history. The Bible presents liberation – salvation – in Christ as the total gift, which, by taking on the levels I indicate, gives the whole process of liberation its deepest meaning and its complete and unforeseeable fulfilment. Liberation can thus be approached as a single salvific process. This viewpoint, therefore, permits us to consider the unity, without confusion, of the various human dimensions, that is, one’s relationship with other humans and with the Lord, which theology has been attempting to establish for some time. This approach will provide the framework for our reflection.’

These words sent shockwaves through the Vatican in the early 1970s. There was concern that those in the Latin American church who were close to the poor were too close to the Marxists who had no belief in Jesus and no concern for the Church. They were preaching a message of political liberation which could be proclaimed with little or no reference to Jesus or the truths of salvation.

Under the leadership of Joseph Ratzinger, the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith published two documents questioning the tenets of this liberation theology. In 1984 Ratzinger published the CDF’s Instruction on Certain Aspects of the ‘Theology of Liberation’[1] and in 1986 their Instruction on Christian Freedom and Liberation[2]. The CDF officials met with various liberation theologians, and over some years, but as Cardinal Muller (one of Ratzinger’s successors as head of the CDF) later noted: ‘Gutiérrez was never censured or commanded to recant, though he was asked to reconsider some of his positions.’[3]

Then there was change afoot in Europe. In 1989, the Berlin Wall came down and the Communist regime in Poland collapsed in the face of opposition by the workers who established the Solidarity movement in the shipyards led by Lech Walesa who was a close confidant of John Paul II. In 1991, John Paul published his encyclical Centesimus Annus marking the centenary of Leo XIII’s great social encyclical Rerum Novarum. John Paul had cause to reflect on the events of 1989. He wrote a paragraph that could have been penned by Gutiérrez:

‘The events of 1989 are an example of the success of willingness to negotiate and of the Gospel spirit in the face of an adversary determined not to be bound by moral principles. These events are a warning to those who, in the name of political realism, wish to banish law and morality from the political arena. Undoubtedly, the struggle which led to the changes of 1989 called for clarity, moderation, suffering and sacrifice. In a certain sense, it was a struggle born of prayer, and it would have been unthinkable without immense trust in God, the Lord of history, who carries the human heart in his hands. It is by uniting our own sufferings for the sake of truth and freedom to the sufferings of Christ on the Cross that we are able to accomplish the miracle of peace and are in a position to discern the often narrow path between the cowardice which gives in to evil and the violence which, under the illusion of fighting evil, only makes it worse.’[4]

In 2023, Cardinal Ludwig Muller noted: ‘Gutiérrez, whom I count as a friend and mentor, never advocated violence or reduced salvation to economic justice. He insisted on the preferential option for the poor, a principle that arises from the priority the poor receive throughout the Bible. He was concerned to demonstrate the consistency of this principle with the tradition of the Church’. Muller went on to say: ‘Over the years I have taken many months-long trips to Latin America, where I have lived among the poor, getting to know their troubles. Gutiérrez’s theology is orthodox, just as their poverty cries out to heaven. Ratzinger recognized both facts’. Remarkably Muller had cause to observe: ‘I myself, strongly influenced by Gutiérrez, was appointed prefect of the CDF by Benedict XVI in 2012.’

When the cardinals of the Roman Catholic Church gathered to elect a new pope after the death of John Paul II back in 2005, there was much speculation that a Latin American would be elected. Bergoglio polled second to Ratzinger. He would have returned home to Buenos Aires fairly sure that by the time of the next conclave he would be too old to be considered for election. No one knew or suspected that Ratzinger would decide to resign in February 2013.

Back home, Bergoglio decided he had another big job to do before submitting his resignation at the age of 75 in 2013. He was going to reinvigorate CELAM (the Conference of Latin American Bishops). Under John Paul II, the Vatican curia had stymied most creative dialogue among such groupings of bishops. The regular synods in Rome had become so staged that even bishops loyal to the curia admitted to boredom, wondering what was the point of going to Rome to read out prepared scripts about prescribed topics, knowing that the final document to emanate from any such meeting was scripted by the Vatican curia with minimal regard for the interventions from the provinces.

There had been a long-running dispute over terminology between the Vatican and the Latin American bishops and theologians, around the concept of the preferential option for the poor. At Puebla (CELAM III, 1979) the bishops took up the call from Medellin (CELAM II, 1968) and affirmed ‘the need for conversion on the part of the whole Church to a preferential option for the poor, an option aimed at their integral liberation.’ The Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith later insisted that the bishops at Puebla spoke of a preferential option for the poor and for the young. Initially John Paul II was wary of the term.

There had not been a meeting of CELAM since Santo Domingo in 1992 (CELAM IV), which under the iron fist of Cardinal Sodano, John Paul’s secretary of state, had fallen into line with the Vatican approach that confined the option for the poor to ethical Christian activity. Soon after his election as pope, Benedict met with four Latin American cardinals, including Bergoglio, and agreed that the Latin American bishops should meet on their own continent, not in Rome, and that they, not the Vatican, should control the agenda. They met at Aparecida in Brazil in 2007. Benedict came, spoke, and gave them licence to speak freely.

Bergoglio was elected to chair the drafting committee. The spirit of Medellin and Puebla was reactivated. Gutiérrez acknowledged that ‘Aparecida mostly happened thanks to Ratzinger.’

The winds of Aparecida blew on the universal church when Benedict convened a bishops’ synod in Rome in October 2012. Francis’s biographer Austen Ivereigh notes that every Latin American bishop at the synod quoted from Aparecida ‘and its missionary, periphery-oriented evangelization’. They struck a chord with bishops from other developing countries. Meanwhile the interventions of the Europeans and Americans lacked ‘fire and energy’ according to Australia’s Cardinal George Pell. One Argentine participant told Vatican Radio, ‘The wind blew from the south.’

In Francis’s apostolic exhortation, Evangelii Gaudium, we get Bergoglio’s distillation of Aparecida. Ivereigh says Evangelii Gaudium ‘was an eruption of the energy and insights from Latin America, stuffed with references to the Aparecida document from 2007.’ In that exhortation, Francis twice uses the term ‘preferential option for the poor’. Quoting Aquinas, Francis says:

‘The poor person, when loved, “is esteemed as of great value”, and this is what makes the authentic option for the poor differ from any other ideology, from any attempt to exploit the poor for one’s own personal or political interest. Only on the basis of this real and sincere closeness can we properly accompany the poor on their path of liberation.’

We thank God for Gutiérrez who in the 50th anniversary edition of his Theology of Liberation wrote: ‘Theological analysis (and not social or philosophical analysis) leads to the position that only liberation from sin gets to the very source of social injustice and other forms of human oppression and reconciles us with God and our fellow human beings.’

To think that John Paul II, Cardinals Ratzinger and Muller, and Gustavo Gutiérrez could all end up on the same page. Like Jesus, they insisted that those like Bartimaeus should not be silenced but encouraged to come into the presence of the one able to give them sight, to liberate them, commissioning them: ‘Go, your faith has saved you.’ Inspired by our church forbears, let’s pray that the leaders of conflict in our world at this time will be able to ‘discern the often narrow path between the cowardice which gives in to evil and the violence which, under the illusion of fighting evil, only makes it worse’. Let’s pray for the liberation of all those who are oppressed.

[1]https://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/congregations/cfaith/documents/rc_con_cfaith_doc_19840806_theology-liberation_en.html

[2]https://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/congregations/cfaith/documents/rc_con_cfaith_doc_19860322_freedom-liberation_en.html

[3] See https://www.firstthings.com/article/2023/03/ratzinger-and-the-liberation-theologians

[4] John Paul II, Centesimus Annus #25