Several years ago, Fr Edward Farrell, the noted spiritual writer of Detroit, took his two-week summer vacation to Ireland to celebrate his favourite uncle’s 80th birthday.

On the morning of the great day, Ed and his uncle got up before dawn, dressed in silence, and went for a walk along the shores of Lake Killarney. Just as the sun rose, his uncle turned and stared straight at the rising orb. Ed stood beside him for 20 minutes with not a single word exchanged. Then the elderly uncle began to skip along the shoreline, a radiant smile on his face. After catching up with him, Ed commented: ‘Uncle Seamus, you look very happy. Do you want to tell me why?’ ‘Yes, lad,’ the old man said, tears washing down his face. ‘You see, the Father is very fond of me. Ah, my Father is so very fond of me.’

It is wonderful when we can each come to realise (usually very slowly) how much ‘the Father is very fond’ of each of us. And yet, in our culture it is not so easy for some to pray to the ‘Father’.

Emeritus Pope Benedict XVI himself spoke of the very real difficulties that some contemporary people have with prayer to ‘God the Father Almighty’:

“Even imagining God as a father becomes problematic, not having had adequate models of reference. For those who have had the experience of an overly authoritarian and inflexible father, or an indifferent father lacking in affection, or even an absent father, it is not easy to think of God as Father and trustingly surrender oneself to him.”

Some pastoral psychologists call this ‘the father wound’ and argue that it may be the most ubiquitous wound on this earth. Indeed, prison chaplains often in their pastoral work note that it is rare to find a prisoner who had a father who loved and validated him.

No wonder then that Jesus calls God ‘Abba’, or ‘Daddy’. Of course, God is beyond gender, but perhaps Jesus used this term because of the ‘father wound’ so common around the earth and over the centuries. Perhaps Jesus wanted us to know that the masculine side of God, his ‘Father-ness’ was trustworthy and good.

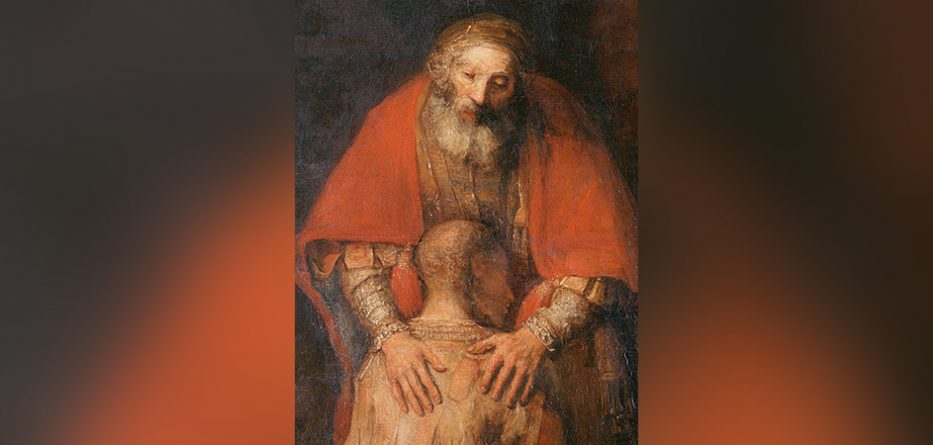

Pastoral theologian Henri Nouwen often reflected about this ‘father wound’. The Return of the Prodigal Son was the very last book he wrote before his early death in 1996. Nouwen noticed in Rembrandt’s image that the father’s right hand is feminine and the left hand is masculine. The feminine hand is on the unshod, vulnerable side of the son. The masculine hand on the shod, protected side. Rembrandt knew we need both a mother’s and a father’s love.

Otherwise, we are in danger of becoming the elder brother. He is the one who never comes to the celebration feast. He never enters the embrace. He represents religion as legalistic, harsh and stone-faced.

In the prodigal son story, the elder brother refuses to acknowledge that he too is wounded. The elder brother struggles with accepting the mercy of the father’s love for sinners like his brother.

As we pray the Creed to ‘God the Father Almighty’ each week, it is good to remember that we are not praying to earn the ‘approval’ of an authoritarian, remote and patriarchal figure. Rather, we are praying to be like Seamus and experience in our hearts the great truth of our faith: ‘the Father is very fond of me’.

This article is part of a series of reflections entitled ‘I Believe…Help My Unbelief’: Meditations on the Creed by Br Mark O’Connor FMS.

Br Mark O’Connor FMS is the Vicar for Communications in the Diocese of Parramatta.