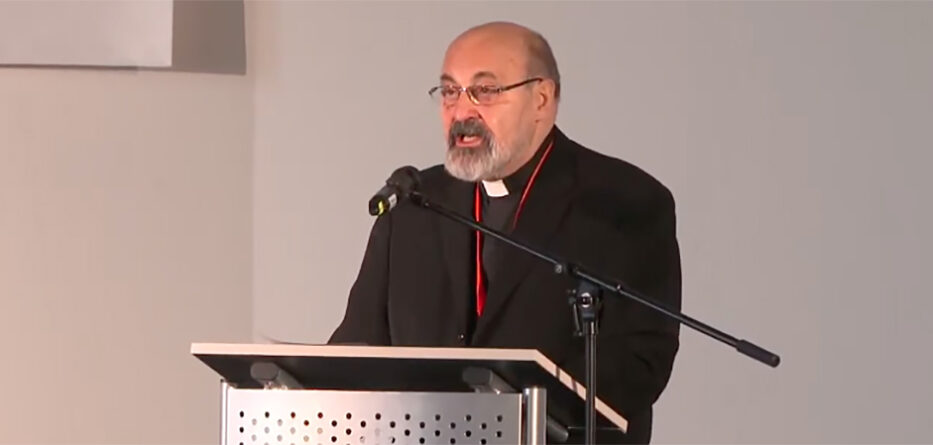

Monsignor Tomáš Halík’s address at the Continental Assembly of the Synod in Prague, the Czech Republic

Spiritual Introduction to the Assembly

6 February 2023

At the beginning of their history, when Christians were asked what was new about their practice, whether it was a new religion or a new philosophy, they answered: it is the way.

It is the way of following the one who said: I am the Way.

Christians have constantly returned to this vision throughout history, especially in times of crisis.

The task of the World Synod of Bishops is anamnesis. It is to be reminded, to revive and deepen the dynamic character of Christianity. Christianity was the way in the beginning, and it is to be the way now and forever. The Church as a communion of pilgrims is a living organism, which means always to be open, transforming and evolving. Synodality, a common journey (syn hodos), means a constant openness to the Spirit of God, through whom the risen, living Christ lives and works in the Church. The synod is an opportunity to listen together to what the Spirit is saying to the churches today.

In the coming days, we are to reflect together on the first fruits of the journey to revive the synodal character of the Church on our continent. It is a short portion of a long journey. This small but important fragment of the historical experience of European Christianity must be placed in a wider context, in the colourful mosaic of the global Christianity of the future. We have to say clearly and comprehensibly what European Christianity today wants and can do to respond to the joys and hopes, the grief and anguish of our whole planet – this planet which is interconnected today in many ways and at the same time is divided and globally threatened in many ways.

We are meeting in a country with a dramatic religious history. This includes the beginnings of the Reformation in the 14th century, the religious wars in the 15th and 17th centuries and the severe persecution of the Church in the 20th century. In the jails and concentration camps of Hitlerism and Stalinism, Christians learned practical ecumenism and dialogue with nonbelievers, solidarity, sharing, poverty, the “science of the cross.” This country has undergone three waves of secularization as a result of socio-cultural changes: a “soft secularization” in the rapid transition from an agrarian to an industrial society; a hard violent secularization under the communist regime; and another “soft secularization” in the transition from a totalitarian society to a fragile pluralistic democracy in the post-modern era. It is precisely the transformations, crises and trials that challenge us to find new paths and opportunities for a deeper understanding of what is essential.

Pope Benedict, on a visit to this country, first expressed the idea that the Church should, like the Temple of Jerusalem, form a “courtyard of the Gentiles”. While sects accept only those who are fully observant and committed, the Church must keep a space open for spiritual seekers, for those who, while not fully identifying with its teachings and practices, nevertheless feel some closeness to Christianity. Jesus declared “He who is not against us is with us” (Mk 9, 40); he warned his disciples against the zealousness of revolutionaries and inquisitors, against their attempts to play the angels of the Last Judgment and to separate the wheat from the chaff too early. Even St Augustine argued that many of those who think they are outside are in fact inside, and many who think they are inside are in fact outside.

The Church is a mystery; we know where the Church is, but we do not know where she is not.

We believe and confess that the Church is a mystery, a sacrament, a sign (signum) – a sign of the unity of all humanity in Christ. The Church is a dynamic sacrament, it is a way to that goal.

Total unification is an eschatological goal that can only be fully realized at the end of history. Only then will the Church be completely and perfectly one, holy, Catholic and apostolic. Only then will we see and mirror God fully, just as He is.

The task of the Church is to keep the desire for this goal ever present in human hearts, and at the same time to resist the temptation to regard any form of the Church, any state of society, and any state of religious, philosophical or scientific knowledge, as final and perfect.

We must always distinguish the concrete form of the Church in history from its eschatological form; that is, we must distinguish the Church on the way, the Church struggling (ecclessia militans), from the victorious Church in heaven (ecclesia triumphans).

To regard the Church in the midst of history as the perfect ecclesia triumphans leads to triumphalism, a dangerous form of idolatry. Moreover, the “ecclessia militans“, if it does not resist the temptation of triumphalism, can become a sinful militant institution.

We confess with humility that this has happened repeatedly in the history of Christianity. These tragic experiences lead us now to the firm conviction that the mission of the Church is to be a source of spiritual inspiration and transformation, fully respecting the freedom of conscience of every human person and rejecting any use of force, any form of manipulation.

Like political power, moral influence and spiritual authority can also be misused, as the scandals of sexual, psychological, economic and spiritual abuse in the Church have shown us, especially the abuse and exploitation of the weakest and most vulnerable.

The permanent task of the Church is mission. Mission in today’s world cannot be “reconquista“, an expression of nostalgia for a lost past, or proselytism, manipulation, an attempt to push seekers into the existing mental and institutional boundaries of the Church. Rather, these boundaries must be expanded and enriched precisely by the experiences of seekers.

If we take seriously the principle of synodality, then mission cannot be understood as a one-sided process, but rather as accompaniment in a spirit of dialogue, a quest for mutual understanding. Synodality is a process of learning in which we not only teach but also learn.

The call to open the “courtyard of the Gentiles” within the temple of the Church, to integrate the seekers, was a positive step on the path of synodality in the spirit of the Second Vatican Council. Today, however, we need to go further. Something has happened to the whole temple form of the Church and we must not ignore it. Before his election to the See of Peter, Cardinal Bergoglio recalled the words of Scripture: Jesus stands at the door and knocks. But today, he added, Jesus knocks from within. He wants to go out and we must follow him. We need to go beyond our current mental and institutional boundaries, to go especially to the poor, the marginalized, the suffering. The Church is to be a field hospital – this idea of Pope Francis needs to be developed further. A field hospital must have the backing of a church that is able to offer competent diagnosis (reading the signs of the times); prevention (strengthening the system of immunity against infectious ideologies such as populism, nationalism and fundamentalism); and therapy and long-term recovery (including the process of reconciliation and healing of wounds after times of violence and injustice).

For this very serious task, the Church urgently needs allies – its journey must be shared, a common journey (syn hodos). We must not approach others with the pride and arrogance of the owners of truth. Truth is a book that none of us has yet read to the end. We are not owners of truth, but lovers of truth and lovers of the only One who is allowed to say: I am the Truth.

Jesus did not answer Pilate’s question with a theory, an ideology, or a definition of truth. But he testified to the truth that transcends all doctrines and ideologies; he revealed the truth that is happening, that is alive and personal. Only Jesus can say: I am the Truth. And at the same time, he says: I am the way and the life.

A truth that was not living and not a way would be more like an ideology, a mere theory. Orthodoxy must be combined with orthopraxy – right action.

The new evangelization and the synodal transformation of the Church and the world constitute a process in which we must learn to worship God in a new and deeper way – in Spirit and in truth.

We must not be afraid that some forms of the Church are dying: “Unless a grain of wheat falls into the ground and dies, it remains a single grain. But if it dies, it bears much fruit.” (John 12:24).

We must not look for the Living among the dead. In every period of the Church’s history, we must exercise the art of spiritual discernment, distinguishing on the tree of the Church the branches that are alive and those that are dry and dead.

Triumphalism, the worship of a dead God, must be replaced by a humble kenotic ecclesiology. The life of the Church consists in participating in the paradox of Easter: the moment of self-giving and self-transcendence, the transformation of death into resurrection and new life.

Through the eyes of faith, we can see not only the ongoing process of creation (creatio continua). In history – and especially in the history of the Church – we can also see the ongoing processes of incarnation (incarnatio continua), suffering (passio continua) and resurrection (ressurectio continua).

The Easter experience of the nascent Church includes the surprise that the Resurrection is not a resuscitation of the past but a radical transformation. Consider that the eyes of even those nearest and dearest to him failed to recognize the Risen Jesus. Mary Magdalene knew him by his voice, Thomas by his wounds, the pilgrims to Emmaus at the breaking of the bread.

Even today, an important part of Christian existence is the adventure of seeking the Living Christ, who comes to us in many surprising – sometimes anonymous – forms. He comes through the closed door of fear; we miss him when we lock ourselves into fear. He comes to us as a voice that speaks to our hearts; we miss it if we allow ourselves to be deafened by the noise of ideologies and commercial advertising. He shows himself to us in the wounds of our world; if we ignore these wounds, we have no right to say with the apostle Thomas: My Lord and my God! He shows himself to us like the unknown stranger on the road to Emmaus; we will miss him if we are unwilling to break our bread with others, even with strangers.

As a “signum“, a sacramental sign, the Church is a symbol of that “universal brotherhood” which is the eschatological goal of the history of the Church, the history of humanity and the whole process of creation. We believe and confess that it is a signum eficiens – an effective instrument of this process of unification. And to accomplish this, contemplation and action must be combined. It requires an “eschatological patience” with the holy restlessness of the heart (inquietas cordis), which can only end in the arms of God at the end of the ages. Prayer, adoration, the celebration of the Eucharist and “political love” are mutually compatible elements of the process of divinization, the christification of the world.

Political diakonia creates a culture of closeness and solidarity, of empathy and hospitality, of mutual respect. It builds bridges between people of different peoples, cultures and religions. At the same time, political diakonia is also a service of worship, part of that metanoia in which human and interpersonal reality is transformed, given a divine quality and depth.

The Church participates in the transformation of the world above all through evangelization, which is her main mission. The fruitfulness of evangelization lies in the inculturation, the incarnation of faith in a living culture, in the way people think and live. The seed of the word must be planted deep enough in good soil. Evangelization without inculturation is mere superficial indoctrination.

European Christianity was considered a paradigmatic example of inculturation: Christianity became the dominant force in European civilization. Gradually, however, the drawbacks and shadows of this type of evangelization became apparent. Since the Enlightenment, we have witnessed in Europe a certain “ex-culturation” of Christianity, a secularization of culture and society. The process of secularization has not caused the disappearance of Christianity, as some expected, but its transformation. Certain elements of the Gospel message that had been neglected by the Church during its association with political power were incorporated into secular humanism. The Second Vatican Council attempted to put an end to the “culture wars” between Catholicism and secular modernity and to integrate precisely these values (e.g., the emphasis on freedom of conscience) into the Church’s official teaching through dialogue. (Hans Urs von Balthasar spoke of “robbing the Egyptians”.)

The first sentence of the Constitution Gaudium et Spes sounds like a marriage vow: the Church has promised modern man love, respect and fidelity, solidarity and receptivity to his joys and hopes, his griefs and anguish.

However, this courtesy was not met with much reciprocity. To “modern man” the Church seemed too old and unattractive a bride. Moreover, the Church’s benevolence toward modern culture came at a time when modernity was just coming to an end. The Cultural Revolution around 1968 was perhaps both the climax and the end of the epoch of modernity. The year 1969, when man stepped on the moon and the invention of the microprocessor ushered in the age of the Internet, can be seen as the symbolic beginning of a new postmodern age. This era has been characterized in particular by the paradox of globalization – on the one hand, near-universal interconnection, on the other, radical plurality.

The darker side of globalization is showing itself today. Consider the global spread of violence, from the terrorist attacks on the United States in 2001 to the state terrorism of Russian imperialism and the current Russian genocide in Ukraine; pandemics of infectious diseases; destruction of the natural environment; and destruction of the moral climate through populism, fake news, nationalism, political radicalism and religious fundamentalism.

Teilhard de Chardin was one of the first prophets of globalization, which he called “planetarisation”, reflecting its place in the context of the overall development of the cosmos. Teilhard argued that the culminating phase of the process of globalization would not arise from some automatism of development and progress, but from a conscious and free turn of humankind towards “a single force that unites without destroying”. He saw this power in love as understood in the Gospel. Love is self-realization through self-transcendence.

I do believe that this decisive moment is happening right now and that the turn of Christianity towards synodality, the transformation of the Church into a dynamic community of pilgrims can have an impact on the destiny of the whole human family. Synodal renewal can and should be an invitation, encouragement and inspiration to all to walk together, to grow, and to mature together.

Does European Christianity today have the courage and spiritual energy to avert the threat of a “clash of civilizations” by converting the process of globalization into a process of communication, sharing and mutual enrichment, into a “civitas ecumenica“, a school of love and “universal brotherhood”?

When the coronavirus pandemic emptied and closed churches, I wondered whether this “lock-down” was not a prophetic warning. This is what Europe may soon look like if our Christianity is not revitalized, if we do not understand what “the Spirit is saying to the churches” today.

If the Church is to contribute to the transformation of the world, it must itself be permanently transformed: it must be “ecclesia semper reformanda“. If reform, a change of form, for example of certain institutional structures, is to bear good fruit, it must be preceded and accompanied by a revitalization of the “circulatory system” of the body of the Church – and that is spirituality. It is not possible to focus only on the individual organs and neglect to take care of what unites them and what infuses them with the Spirit and life.

Many “fishers of men” today have similar feelings to the Galilean fishermen on the shores of Lake Gennesaret when they first encountered Jesus: “We have empty hands and empty nets, we have worked all night and caught nothing.” In many countries of Europe, churches, monasteries and seminaries are empty or half-empty.

Jesus tells us the same thing he told the exhausted fishermen: Try again, go to the deep. To try again is not to repeat old mistakes. It takes perseverance and courage to leave the shallows and go to the deep.

“Why are you afraid – don’t you have faith?” Jesus says in all storms and crises.

Faith is a courageous journey to the deep, a journey of transformation (metanoia) of the Church and the world, a common journey (syn-hodos) of synodality.

It is a journey from paralyzing fear (paranoia) to metanoia and pronoia, to foresight, prudence, discernment, openness to the future, and receptivity to God’s challenges in the signs of the times.

May our meeting in Prague be a courageous and blessed step on this long and demanding journey.