To describe Opus Dei as mundane would likely strike most readers as odd, if not perverse. After all, the group has been embroiled in controversy since its birth, attracting criticism for its secretive practices, its members’ collusion in Francisco Franco’s dictatorship in Spain, and its often rigidly conservative beliefs. But the most literal meaning of “mundane” is “of this world”; and this is how Opus Dei understands itself, and how it has come to describe its charism. The key to understanding this group is ordinary secularity.

Throughout the history of Christianity, the tension between this-worldliness and otherworldliness has drawn many boundaries and defined countless identities. For someone like Augustine of Hippo, the two poles were quite clear: the realm of the transcendent is the City of God, the land of the promise of eternity; and the secular—saeculum—is the time between now and the Second Coming, before the wheat is sorted from the tares. To be self-consciously secular, or mundane, is to consider oneself wholly and truly of this age.

And this is indeed how Opus Dei sees itself. In the two-volume Opus Dei: A History, two senior members of the group, José Luis González-Gullón and John F. Coverdale, try to pin down the specific qualities that have given form to Opus Dei. And what they’ve come to see, nearly a century since the group was founded, is that it’s inextricably tied to the ordinariness of this age, to “a message that unites the human and the religious.”

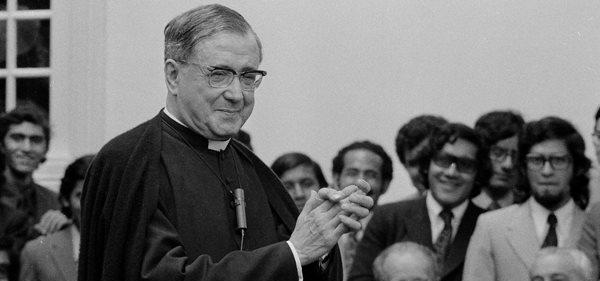

Opus Dei was founded by the priest Josemaría Escrivá de Balaguer in Spain in 1928. During the Spanish Civil War, its members consolidated their presence in the country and strengthened their grip on its cultural, political, and professional circles. Few Commonweal readers will be unaware of Opus Dei’s more than slightly unusual history. A novelty in the Church, it began garnering the approval of certain key figures, especially Popes Pius XII and John Paul II. This allowed it to grow from a small association of Spanish lay Catholics and a handful of priests to become a one-hundred-thousand-strong “personal prelature”—a special status in canon law that grants it jurisdiction over all its members, outside the geographical diocesan system.

Opus Dei’s rapid ascent has been regarded with suspicion both inside and outside the Church. Its members are known for being fervently outspoken about their positions on such contested social issues as abortion and same-sex marriage (positions, it should be said, that many ordinary Catholics outside Opus Dei share). Their belief in the rigid separation of the roles of men and women, with the latter being instructed by the group to serve the former, has led many to find them uncomfortably conservative, even reactionary. Yet this is not where they get the most flak.

Escrivá believed in the necessity of meeting God, and sanctifying oneself, within the ordinary responsibilities of everyday life. In concrete terms, this implied a total, wholehearted acceptance of the professions—forms of life distinctive of the modern age. Among the ranks of Opus Dei, it is common to find lawyers, bankers, academics, journalists, and politicians of significant status. Opus Dei prepares and guides its members to an extraordinary extent. They all receive attentive spiritual formation based largely on Escrivá’s book The Way; many end up at one of the group’s well-funded colleges and universities, institutions that offer the subjects that make up the modern quadrivium: philosophy, law, economics, and communications.

All this is designed to help the members of Opus Dei burrow deep into their workplaces—from banks and law firms to universities and government ministries—and to make the most of their professional careers. As one member once told me, they demonstrate through their professional activities how the gifts of Christianity are finely tuned by the instruments Opus Dei provides. A typical member of Opus Dei is a well-formed member of the professions with a well-articulated, albeit somewhat idiosyncratic, sense of what it means to be a modern Christian.

During the years of Franco’s dictatorship, many of his closest allies and ministers were members of Opus Dei. The opusdeístas, as their critics would call them, staffed many ministries and offices that kept alive one of Western Europe’s longest-lasting authoritarian dictatorships. Yet as international commentators in the 1960s observed, these “ultra-Catholic” technocrats were also instrumental in delivering Spain from its only partly industrialized, mostly agrarian past. The opusdeístas brought the country, kicking and screaming, into the modern world. For their allies within Franco’s regime, and those who still today hail them as the country’s modernizers, they are considered trailblazers of rationalized statecraft and administration; to their critics, they were exploitative opportunists who instrumentalized Cold War free-market economics to keep Spain, morally and culturally, in a premodern limbo—a critique the authors of Opus Dei: A History don’t have much to say about.

The truth lies somewhere between the two. It would be absurd to deny that many opusdeístas were complicit in some of the most unsavory aspects of Franco’s regime, though many in Opus Dei write this off as more accidental than intentional. González-Gullón and Coverdale claim that there’s little in the political conduct of the opusdeístas that is specifically attributable to their membership in Opus Dei. “All members,” they stress, “enjoy freedom in political and cultural matters.” All Opus Dei does, they insist, is fulfill a “purely spiritual and evangelizing purpose.” But the distinction here is too neat. Even if Franco’s Opus Dei allies were not exactly controlled by their spiritual advisors, the convictions that motivated their work certainly did arise from the whole group’s sense of what the modern world had to offer, and what needed to be changed.

González-Gullón and Coverdale do venture some minimal reproaches of Opus Dei’s past leadership. In 1956, in preparation for his fifth government, Franco approached several leaders of Opus Dei, asking for their advice on ministerial appointments. This marked the beginning of the group’s intimate link with Franco’s regime. Acting on the counsel of the priest Antonio Pérez Hernández, a senior member of Opus Dei, many opusdeístas were brought into the Francoist fold. González-Gullón and Coverdale admonish Pérez, writing that he “clearly violated” Escrivá’s wishes.

What the authors do not tell us is that Pérez had already made his aim clear two years before: “Ecclesiastical authority,” he declared at a 1954 conference attended by many of Spain’s political and religious leaders, “must have the possibility to produce legal effects.” Pérez would later leave Opus Dei and the priesthood in 1959, but two years later, in a speech marking the creation of the Opus Dei–run University of Navarra, Escrivá thanked Pérez for his work and praised his guidance in front of hundreds of students, parents, and noteworthy public figures.

Some of Opus Dei’s critics seem to miss what is most distinctive about the group. One may consider its moral views somewhat archaic, but it seems like a mistake to label a bunch of technically skilled financiers and politicos as premodern. The “mundanity” stressed by González-Gullón and Coverdale offers a way out of this apparent contradiction. To embrace secularity implies, as Augustine would have it, giving oneself to history, and more specifically to the age in which one lives. This is, in one sense, diametrically opposed to what some call the “Benedict Option,” whereby the faithful Christian retreats from the world and lives as a recluse in comfortably remote cloisters.

By contrast, to be of the age, or to give oneself to the ordinariness of everyday life, requires that one not wholly repudiate those identities, values, and practices that make the present what it is. Opus Dei began at one of Western Europe’s most significant junctures—when the sickly empires of early modernity gave way to international trade—and the group never tried to escape from the age to which it belonged: a modernity colored by the travails and hopes of an ascendant middle class. It had to learn the tricky moral and cultural steps of capitalism’s awkward dance with Christianity.

In one sense, Opus Dei’s modern mundanity can be summed up in Escrivá himself. Born into a middle-class family with unrealized claims to nobility, his studies at the seminary were accompanied by legal training. Even before his ordination, he believed it necessary to become a doctor of the law: jurisprudence, along with commerce, were the keys to society. Throughout his life, he would admire and praise figures capable of saving banks or lifting businesses out of bankruptcy. The luxurious decadence of the early-twentieth-century European nobility was denied him, but he did not look to the working classes and the movements they created for inspiration. His conservatism, and that of the movement he founded, were typical of the striving middle classes intent on technical competence and rational administration.

This formula didn’t change much in the 1960s and ’70s, years that marked Opus Dei’s international expansion. Though the group is now present in more than eighty countries, its institutional culture remains similar to what it was from the start, a fact less surprising when one considers that almost half the group’s members are Spanish and over one-third reside in Spain. The language González-Gullón and Coverdale use to describe the period during which Opus Dei went international underscores the consistent moral and cultural conservatism of the group. Starting in the sixties, they write, many people began rejecting “a regulated world that sought economic prosperity.” Seduced by “neo-Marxist and Freudian ideas,” a “youth rebellion led to widespread public abuse of alcohol and drugs, as well as promiscuous sexual activity.” All these “excesses,” they comment, “were justified by a perceived right to self-satisfaction.”

Many have noted that you won’t find many members of Opus Dei defending society’s poorest and most marginalized. That may be true, but then it’s equally hard to find great numbers of non-Catholic white-collar professionals latching onto causes that do not immediately concern them. The source of the problem may not be Opus Dei itself, but the bourgeois worldview that many of its members, including its founder, represent: a way of engaging with the world that prioritizes extraction and use, that lacks sensitivity to the wants and needs of the less fortunate, and is chronically unaware of both one’s complicity in the system and one’s ability to facilitate transformation. All the cracks and blemishes in society are explained away as signs of growth and development and are to be met with ever-greater, ever-more-invasive technical solutions. This is what Pope Francis has called the “technocratic paradigm.”

Nevertheless, what González-Gullón and Coverdale have achieved in this work is striking: an impressive overarching narrative of Opus Dei’s nearly century-long history. This chronologically ordered, textbook-like account of the group’s evolution fills a real gap, providing valuable information not available even in John Allen’s Opus Dei: An Objective Look Behind the Myths and Reality of the Most Controversial Force in the Catholic Church. But what is perhaps most remarkable about the book is how forthright its authors are about Opus Dei’s blemishes, given that they are themselves members.

Their relative candor is no doubt part of the new strategy adopted by Opus Dei around the start of the 2000s. When the film version of The Da Vinci Code came out in 2006, the group once again returned to public attention, much of it hostile. But this time Opus Dei reacted differently. It did not hide behind the silence its founder extolled, nor did it mount a belligerent counter-offensive. Under the guidance of Juan Manuel Mora, Opus Dei’s communications director, the group welcomed curious observers. Mora instructed the communications team to host them in the group’s many residences and centers around the globe, to treat them well, to be open, and to answer questions—in short, to pull away the veil. In writing their book in the manner they have, González-Gullón and Coverdale have done something similar.

But to many readers, Opus Dei will still seem like an oddity, no matter how much it’s demystified. And in the context of the twenty-first-century Catholic Church, it issomewhat odd. For those following the raging arguments between self-styled “traditionalist” and “liberal” camps within the Church, a group so blissfully uninterested in these quarrels may seem a little out of step. A lot of what these Catholic cultural discussions stem from, on either side of the divide, is an attempt to recover Christianity from its corrupted state. The traditionalists think the Church went wrong by getting entangled with liberal modernity; the liberals think the pre-conciliar Church went wrong by chasing power instead of Christ-like love. Both sides think the Church has been polluted by history—or, one might say, by the mundane.

Precisely because of its own resolute mundanity, Opus Dei chooses not to follow suit. “I don’t get the traditionalists,” an Opus Dei member once told me. “What’s so special about the Tridentine Mass?” The group welcomes history; it finds no reason to challenge modernity, but it remains convinced that the Church will never entirely give way to the pressures of a post-religious world. Material progress will prevail, but so will the Church, inevitably and unproblematically. And surely this is, for better and for worse, very similar to the way many ordinary Catholics see the relationship between their faith and the age they belong to.

Daniele Palmer lives in London, where he teaches history and works in community organizing.

Reproduced with the permission of Commonweal Magazine.