By Bishop Vincent Long OFM Conv, Catholic Outlook, December 2016

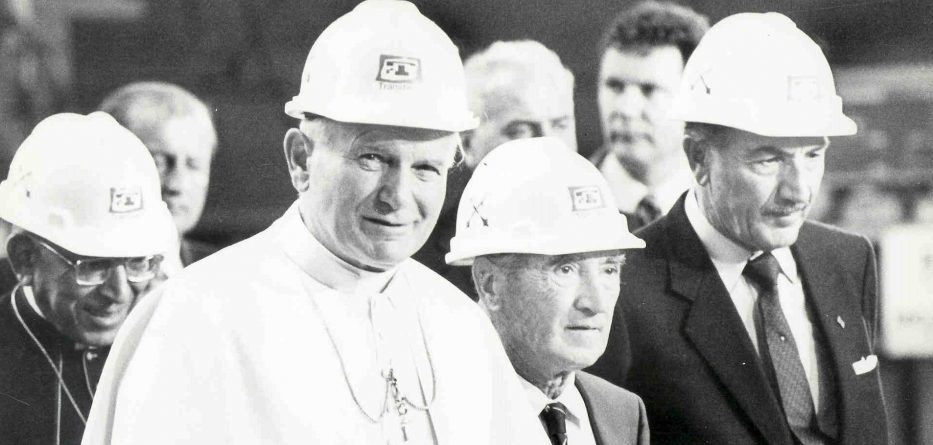

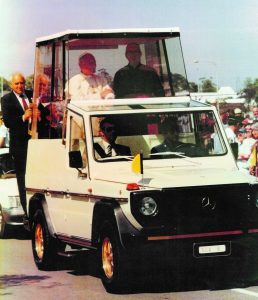

Thirty years ago, on 26 November 1986, St John Paul II visited the Diocese of Parramatta to address a large crowd of workers gathered at the Transfield factory in Powers Road, Seven Hills. This large engineering factory hosted 12,000 people when it was temporarily cleared of much of its machinery.

The Pope opened his address with a reflection on his early life as a quarry and factory worker.

“These were important and useful years in my life. I am grateful for having had that opportunity to reflect deeply on the meaning and dignity of human work in its relationship to the individual, the family, the nation, and the whole social order.”

His experience and reflection led him to “proclaim again” his “own profound conviction” that “human work is a key, probably the essential key, to the whole social question, if we try to see the question really from the point of view of man’s good.”

The Catholic Church has developed a body of teaching that that seeks to identify and address a range of social issues. The origins of modern Catholic Social Teaching, with its emphasis on work and economic relations, are found in Pope Leo XIII’s great social encyclical of 1891, Rerum Novarum. The connection between faith and work is illustrated by a passage in St John Paul II’s 1981 encyclical commemorating the 90th anniversary of Rerum Novarum:

“In order to achieve social justice in the various parts of the world, in the various countries, and in the relationships between them, there is a need for ever new movements of solidarity of the workers and with the workers. This solidarity must be present whenever it is called for by the social degrading of the subject of work, by exploitation of the workers, and by the growing areas of poverty and even hunger. The Church is firmly committed to this cause, for she considers it her mission, her service, a proof of her fidelity to Christ, so that she can truly be the “Church of the poor”. (Laborem Exercens, paragraph 8, italics in original.)

St John Paul II’s encyclicals in 1981 and 1991 (Centesimus Annus) commemorating Rerum Novarum and a range of his other writings have established the framework for, and much of the content of, modern Catholic Social Teaching on work, workers’ rights and economic systems.

Both Pope Benedict XVI and Pope Francis have continued to apply and develop this teaching in the context of the emerging issues of the early 21st Century.

The world of work has changed dramatically since St John Paul II spoke to the workers at Seven Hills. The disruption of earlier patterns of employment as a result of technological changes and globalisation in Australia and elsewhere have been profound.

The ‘Brexit’ vote in Britain in June 2016 to leave the European Union and the election of Donald Trump as US President in November 2016 owe much to a widespread disillusionment with the personal, family and social impact of economic changes over the past few decades.

It is true that other factors came into play in the decisions, but without the loss of faith in contemporary economic policies, many believe that those decisions would not have been made.

In Australia, we have not had such a cathartic event, but the public debate has been changed. Recently, we have seen substantial public discussion about the exploitation of low-paid workers, particularly foreign workers.

Over recent years there has been an understandable interest in improving productivity, but often the proposals to improve productivity are, in the eyes of the workers involved, at least, proposals to cut wages, reduce reasonable working conditions and increase job insecurity.

The Church must respond to the changing economic realities and speak on behalf of those who have been prejudiced or ignored by these changes.

How should the Church respond? The answer to this question might start with the address given by St John Paul II at Seven Hills. He recognised the positive aspects of economic change, but warned against “ways of thinking” and proposed a way forward:

“In the past, the Church has consistently opposed ways of thinking which would reduce workers to mere ‘things’ that could be relegated to unemployment and redundancy if the economics of industrial development seemed to demand it.

“No one has a simple and easy solution to all the problems connected with human work. But I offer for your consideration two basic principles.

“First, it is always the human person who is the purpose of work. It must be said over and over again that work is for man, not man for work. Man is indeed ‘the true purpose of the whole process of production’. Every consideration of the value of work must begin with man, and every solution proposed to the problems of the social order must recognise the primacy of the human person over things.

“Secondly, the task of finding solutions cannot be entrusted to any single group in society: people cannot look solely to governments as if they alone can find solutions; nor to big business, nor to small enterprises, nor to union officials, nor to individuals in the work force. All individuals and all groups must be concerned with both the problems and their solutions.”

St John Paul II’s message in 1986 is particularly relevant to the work and economic issues that confront Australia in 2016.

First, we have to be clear about our values: we must recognise the primacy of the human person.

Second, the formulation of solutions to contemporary issues must be based on cooperation, and not a contest, between sectional interests and groups: solutions cannot be solely determined by economic considerations.