10 December is the United Nations’ International Human Rights Day

When we think of human rights, we usually imagine a theatre of conflict. In it, human rights need to be fought for in the face of fierce opposition. We think, for example, of the right to freedom of movement and of religion denied to the Uighur people within China. Or perhaps of the rights of Australians to religious freedom or to freedom from discrimination on the basis of gender or race. We see rights as things that we must defend and campaign for against fierce and misguided opponents.

That view reflects a history in which the human rights of people are respected only after people have agitated for them for generations. The right of human beings to be free from slavery, for example, took centuries to be accepted and still needs to be defended in the face of new forms of slavery.

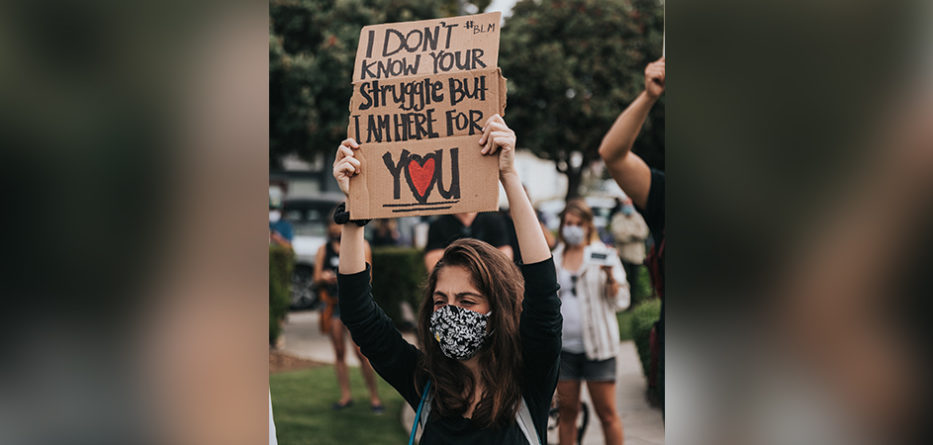

A more complete view of human rights, however, does not see them as isolated and separate things that divide society into supporters and opponents. It sees them as different ways of spelling out why human beings matter and what respect for them involves. They express what we ought to be able to expect from one another as our fellow human beings in different situations, and what we owe to one another. Ideally, human rights unite us as human beings and do not divide us. In them we celebrate each other’s shared humanity, recognising that our dignity as persons does not depend on our race, religion, political views, virtue, gender or virtue. Nor does it depend on public opinion. An unpopular person who has committed a murder has as much right to food, shelter and security as does a revered saint. Both are human beings, and so are entitled to respect for their shared human dignity.

In times of conflict, it is easy to regard rights as things that divide us as a society. That is a pity. A society is better in which we rejoice in our shared dignity and the rights that follow from it, and ask how we can ensure that each person in our society is treated with due respect. We shall be united, for example, in demanding that prisoners are not held in cells where the summer temperature can reach over 40 degrees, that children are not put in adult prisons, that people are paid proper wages, and that Indigenous people are not discriminated against.

It is also easy and mistaken to think that human rights are established by governments and by the laws that they pass. That would mean that governments may take away rights and grant them at will. Rights belong to us as human beings, and the role of governments is to defend them and, where necessary, to pass laws that ensure people receive due respect. In a society where all people respected one another, there would be no need to protect rights by passing laws. Because our society is composed of sinful human beings, however, laws are necessary.

In all societies, there will be occasional conflict about what respect demands of us. In it, people appeal to different rights. In Australia, such conflict has recently arisen between the right to religious freedom and the right to the freedom from discrimination on the basis of gender and sexual preference. The challenge is to move beyond seeing this as the need to choose between one right and another. We should rather ask how we can give persons the respect articulated in each of the rights in conflict. This involves negotiation based on listening and assuming good faith.

Fr Andrew Hamilton SJ writes for Jesuit Communications and Jesuit Social Services.