Fourth Sunday of Lent

Readings: JOSHUA 5:9–12, PSALM 33(34):2–7, 2 CORINTHIANS 5:17–21, LUKE 15:1–3, 11–32

30 March 2025

Gospel Reflection: From homesickness to homecoming

We are striving this Lent to stay close to Jesus. We want him at our side as we battle the enemies of the soul: the devil, the world, the flesh. Not content to be purely defensive, we also accept his invitation to climb the summit. The ascent to contemplatio is demanding, so it’s wise to stay within arm’s length of the Lord. When we slip and falter, we can more easily reach for him.

Nonetheless, despite our noble aspirations, we frequently resemble the prodigal son. We are all too capable of repeating the prodigal’s great mistakes: we abandon our Father’s home, and we squander our inheritance. Our sensuality, our love of comfort, and especially our pride, cause us to reject God’s grace and fall into sin. But if we’re inclined to imitate the prodigal’s folly, we should heed his good sense, too. At rock bottom, literally in the pigsty, “He came to his senses” (Lk 15:17).

We are not defined by our past; we are defined by our divine filiation. We are sons and daughters of God, and none of our shortcomings or offences can ever change that.

We must never be disheartened by our weakness. We must not dialogue with shame. We are not defined by our past; we are defined by our divine filiation. We are sons and daughters of God, and none of our shortcomings or offences can ever change that. Even amid extreme degradation, when we are disgusted with ourselves and full of self-reproach, we might at least open our hearts to feeling homesick. We may not be ready to seek mercy—love we do not deserve— but we make a good start by acknowledging our longing for home. Homesickness was enough to turn the prodigal’s gaze towards his father’s house, and it’s the first step in our own metanoia, too.

St Luke tells us that sinners and tax collectors sought the company of Jesus to hear what he had to say (Lk 15:1). We can imagine what it must have been like, to be there in person, listening to the Master’s sermons—observing his interactions with strangers whom he seems to know and love in a very personal way. His demeanour and his actions evoke the warm family atmosphere of the Father’s home. Such warmth and hospitality invariably elicits the homesickness which precipitates conversion.

In every generation since, the saints have imitated Jesus. Those who are closest to God are seldom, if ever, scandalised by the sins of others.

In every generation since, the saints have imitated Jesus. Those who are closest to God are seldom, if ever, scandalised by the sins of others. They may show horror at sin, but what predominates is their pity and tenderness towards sinners. When Mother Teresa’s Missionaries of Charity moved to the Bronx in the 1970s, they distinguished themselves by smiling and greeting everyone they passed, without exception. A trans streetwalker, accustomed to contempt and abuse, counted herself lucky when neighbours looked through her as though she was invisible. Only the sisters would greet her by name and show her affection as they passed by. When she got sick and entered palliative care, she asked the sisters to help her reconnect with God, whom she remembered from her childhood catechism. The sisters’ kindness had evoked a longing for home.

Every one of us plays the role of the prodigal son. We repeat his mistakes, but we also share the joy of his homecoming. This not only inspires our gratitude and confidence, but it also equips us to communicate God’s extravagant love. Every time we come to our senses, and start the journey home, we can greet sinners on the road with familial recognition. Our affection and kindness might help them turn their gaze towards our Father’s home. Homesickness precipitates conversion.

Fr John Corrigan

Spiritual Direction: Love will work a way

How typical of Jesus to speak of a heart that is not complete—to tell us the story of a broken relationship, a theme that echoes throughout humanity. If our relationships weren’t fractured, we would not experience war or see lives shattered.

Why do relationships fall apart? It’s easy to generalise, blaming one side for being completely off track, like the young man in the parable. While that might be true, perhaps there is more to it than just that. Relationships often break because people themselves are already broken in some way. Unresolved wounds from our past can dull our ability to truly see and hear others for who they are, making it difficult to live fully. As a result, relationships fracture. It can be very hard to live with, and most of us don’t want to live like that anyway. God couldn’t live with it, so he sent Jesus, who not only took on our humanity, but also showed us the path to healing—a path he embraced himself.

Unresolved wounds from our past can dull our ability to truly see and hear others for who they are, making it difficult to live fully.

There was an old black and white film I saw years ago about a woman who was from a very rich family. She formed an attachment with someone who no doubt loved her, but was a hopeless spendthrift and did not know the meaning of responsibility. Against her family’s wishes, she eloped with him. They managed to go through all the money she had, and when almost at the end, she discovered she was pregnant. This news, of course, demanded a whole new way of thinking and managing. He would have to get a job and be the provider. This was all too much for him, and as a way out, he said, “Well, you are the one on the merry-go-round, you get off it.” In other words, end the pregnancy and then everything would be fine, except of course it wouldn’t. She finally saw the man she loved for who he really was. There was a stunning and gripping image of him going off into the dark. Given her situation, she had no alternative but to return home. No one was home when she got there, so she simply sat in a darkened room. Her always loving brother came in, and finding her crying, he listened. She didn’t know what to do. Her brother simply said, “Keep loving, and one day the love you have will work a way.”

Pour love into whatever you do, whoever you are, and you give God permission to bring you and others home, firstly to himself, and then to each other— that’s metanioa again.

So, what do we do? Coming home may not always look like the story in today’s Gospel, but it’s guaranteed if we keep loving. Ultimately, we are always returning to the Father, the source from which Love originates and flows. It isn’t easy, but it is possible. The secret is to keep our gaze on God—not ourselves, not even the one who is estranged from us. Jesus once said to Catherine of Sienna, “Keep your eyes on me and I will keep my eyes on them.” We can’t bring anyone home, but God can, even by a different, unexpected road.

If you had in your mind an image of God carrying someone home, who would you choose? Is there a family member you want brought home? Are you the one who needs to come home? Are you thinking of our warring earth that needs bringing home? Pour love into whatever you do, whoever you are, and you give God permission to bring you and others home, firstly to himself, and then to each other—that’s metanioa again.

Mother Hilda Scott OSB

Artist Spotlight

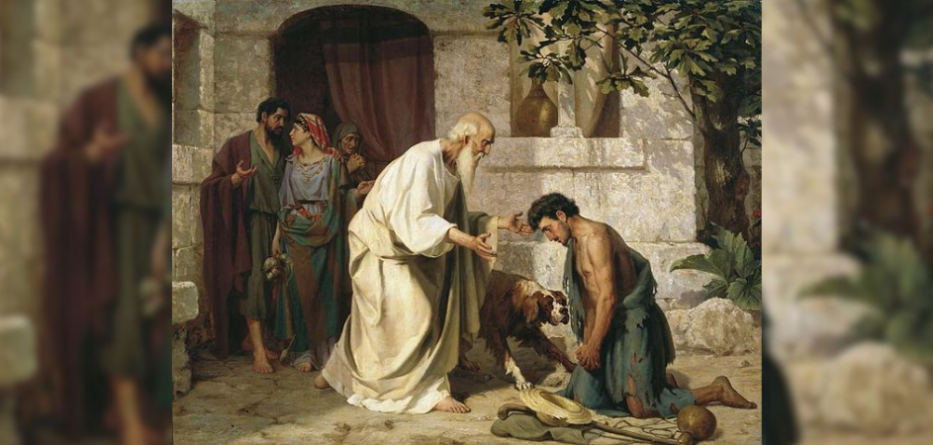

The Prodigal Son (1882) Nikolay Dmitrievich Losev (1855−1901) Oil on Canvas. Bristol Museum & Art Gallery, UK. Public Domain.

Nikolay Dmitrievich Losev, born in 1855, was a prominent Russian artist who began his formal art education in 1870. His works frequently depicted historical narratives intertwined with scenes from everyday life. Renowned for his meticulous attention to detail, Losev’s subjects were vividly portrayed, often revealing a wide spectrum of emotions. This is nowhere more evident than in his The Prodigal Son (1822), now housed in the Bristol Museum Art Gallery in the United Kingdom.

Losev uses light to great effect, the viewer’s eye immediately focused on the father, his white robe contrasting with the boy’s dishevelled clothes and appearance. Every gesture of the father points to his unconditional forgiveness—his bent figure and his outstretched hands. Even the family dog seems to echo his master’s attitude.

The son, worn out by suffering and worry, seems to exhibit sorrow and repentance. But in the context of the theme of this year’s Lenten Program, metanoia—meaning a complete change of heart—one wonders if at this point the son is truly sorry. St Luke hints that the boy, sitting in the pigsty, is only sorry for himself. He decides that full sonship will never be his again and will be satisfied to be taken in merely as a servant. We would hope that once the son realised the magnificence of his father’s love and acceptance, a second, more authentic, conversion took place.

To the left of the father, two servants seem to be discussing the implications of the scene, while in the background, perhaps it is the boy’s mother, her hands clasped in joy at the answer to her prayers.

Losev was only 46 when he died in 1901.

Monsignor Graham Schmitzer

Fr John Corrigan is an assistant priest in the Diocese of Ballarat. He currently ministers in the parish of Sunraysia, centred on Mildura in the far north of Victoria, although he is also known in other parts for his “Blog of a Country Priest,” and for regular appearances on Network Ten and Foxtel’s Mass For You At Home.

Mother Hilda Scott OSB is the former abbess of the Benedictine Sisters at Jamberoo Abbey, NSW. Before becoming abbess, she served as prioress, novice mistress, and vocation director, and engaged in spiritual direction, retreat giving, and talks at the Abbey Retreat Cottages. She gained wider recognition through the ABC TV documentary, The Abbey. Before 1990, she was in a different religious order, teaching, working with youth and children, and doing pastoral work in parishes. Just before joining Jamberoo, she lived in a caravan park among the most disadvantaged in society.

Monsignor Graham Schmitzer is the retired parish priest of Immaculate Conception Parish in Unanderra, NSW. He was ordained in 1969 and has served in many parishes in the Diocese of Wollongong. He was also chancellor and secretary to Bishop William Murray for 13 years. He grew up in Port Macquarie and was educated by the Sisters of St Joseph of Lochinvar. For two years he worked for the Department of Attorney General and Justice before entering St Columba’s College, Springwood, in 1962. Mgr Graham loves travelling and has visited many of the major art galleries in Europe.

With thanks to the Diocese of Wollongong, who have supplied this reflection from their publication, METANOIA – Lenten Program 2025. Reproduced with permission.