A book about a lecture series? That doesn’t sound very compelling. But Reasons for Hope: Hélder Câmara, Global Catholicism and the Australian Church by historian Julie Thorpe is a rambunctious work that employs a 40-year lecture series to shine a light on developments in post-conciliar Catholicism.

The book opens with a profile of Dom Hélder Câmara, the Archbishop of Olinde and Recife, Brazil from 1964 to 1985. He attended all four sessions of the Second Vatican Council and, towards its end, helped organize the Pact of the Catacombs, signed by 40 bishops, asking their brother bishops to adopt evangelical poverty and eschew all trappings of power. A profoundly conservative young man, Câmara became a proponent of liberation theology and was an outspoken opponent of the Brazilian military junta.

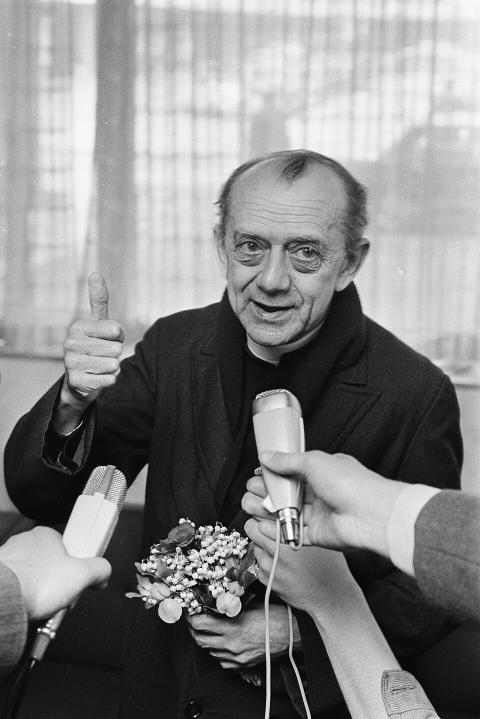

In 1985, Câmara accepted an invitation from Br. Mark O’Connor, a Marist Brother of the Schools, to come to Australia and speak in Melbourne, Sydney and Adelaide. The Brazilian prelate was charismatic in the strict, Christian sense of the word: Nicknamed “the Electric Mosquito” by journalists because of his diminutive physical stature and dynamic personality, his gifts were of the Holy Spirit, and he possessed the interior freedom that comes with a deep awareness of the source of one’s gifts.

After Câmara left, the Marist provincial asked Br. O’Connor, “what remains?” It was not just their ongoing ministry to young people and work for social justice. Câmara had left “something of joy, and hope” writes Thorpe, “a greater sense of the world, the place of prayer and the creed, the sharing of the eucharist, all on display in the person and stories of Hélder Câmara and the events surrounding him in the month of his May visit.” O’Connor had the intuition that bringing leaders from the universal church to Australia, with their stories, could help nurture that joy, that hope. Just as importantly, he had the determination to make it happen.

The 1985 visit coincided with the synod of bishops marking the 20th anniversary of the conclusion of the Second Vatican Council. The lecture series that Br. O’Connor conducted for the next 40 years illustrated the ongoing reception of Vatican II that had been the focus of the 1985 synod. Conciliar texts are not self-explanatory. Certain verbal constructions represent a compromise between different positions. The two central hermeneutical keys — aggiornamento, or bringing up to date, and ressourcement, or returning to the sources — run through all the documents. But neither key is given priority over the other by the documents themselves. The Câmara lecture series was an ongoing discussion about the significance of Vatican II for the church in Australia and throughout the world.

Dom Hélder Câmara in 1970. Image: Wikimedia Commons

The list of lecturers is impressive, a veritable “who’s who” of post-conciliar Catholicism. Cardinal Basil Hume, the archbishop of Westminster, made the trek to Melbourne in 1988 and delivered a powerful reflection on how he came to understand that “life’s purpose was not now, but later on,” writes Thorpe. “And that ‘later on,’ he saw then, had to be total, complete, endless, no desire left, and ‘the world could not offer me that.’ Hints and suggestions, like his first ‘exhilarating’ love. But to be loved, and never to be robbed of it, ‘there was the secret of life.'” This is the most underappreciated reality of post-conciliar theology: Our dreams are too small.

The Jesuit Cardinal-Archbishop of Milan, Carlo Maria Martini, delivered one of the Câmara lectures, as did the Dominican Cardinal-Archbishop of Vienna, Christoph Schönborn. Nor was the lectern reserved for prelates: Brazilian theologian Maria Clara Bingemer delivered the lecture in 2000 and Sr. Nathalie Becquart did so in 2023.

In listing the speakers, Thorpe also situates the lecture amidst the other things the speaker was saying and doing. So, for example, she not only quotes from Chicago Cardinal Francis George’s talk, but also cites his contribution to Commonweal magazine’s famous symposium on the future of liberal Catholicism, in which the late cardinal called it an “exhausted” project.

Thorpe spends significant time discussing the 2001 lecture and visit by Cardinal Jean-Marie Lustiger, the archbishop of Paris, a convert to Catholicism whose Jewish family was murdered in the Shoah. While in Australia, Lustiger engaged in a public discussion with the former editor of Australian Jewish News, Sam Lipski, in which the cardinal spoke powerfully about his experience of Jewish otherness at the end of World War II:

At the liberation of Paris when the Germans were defeated, we spoke about the camps. There was in Hotel Lutetia the centre where the deported, the survivors, came back from the camps to Paris. It was not possible to speak within the Resistance, the main resistance, men and women, to speak about Jews. We were not resisters. We were only Jews. We were victims. The antisemitism of those people who were resisters was so instinctive. It was necessary to fight after World War Two, in liberated France, to be recognized as a real citizen.

This is chilling, but unsurprising, especially as we look around and witness how pedestrian antisemitism has become in our own day.

This book can be a bit frustrating. At times, it seems written in a stream of consciousness. Some paragraphs are so packed with unexplained references and unexplored insights, they seem like a crowded, noisy, thrilling cocktail hour. Stay for the dinner, however. The narrative arc is of an Australian Catholic Church that remained engaged with the major issues confronting the universal church through a well-planned and brilliant lecture series organized and structured by the indefatigable Br. O’Connor. In tumultuous times, these lectures helped the church understand itself. Thorpe’s book catalogues the fruit of that work, and shares it in a compelling way with students of contemporary Catholicism. We owe them both a debt of gratitude.

Reproduced with permission by National Catholic Reporter (NCR) and Michael Sean Winters.