The road in the end taking the path the sun had taken,

into the western sea, and the moon rising behind you

as you stood where ground turned to ocean: no way

to your future now but the way your shadow could take,

walking before you across water, going where shadows go,

no way to make sense of a world that wouldn’t let you pass

except to call an end to the way you had come,

to take out each frayed letter you had brought

and light their illumined corners; and to read

them as they drifted on the western light;

to empty your bags; to sort this and to leave that;

to promise what you needed to promise all along,

and to abandon the shoes that had brought you here

right at the water’s edge, not because you had given up

but because now, you would find a different way to tread,

and because, through it all, part of you would still walk on,

no matter how, over the waves.

– David Whyte, Finisterre (2016).

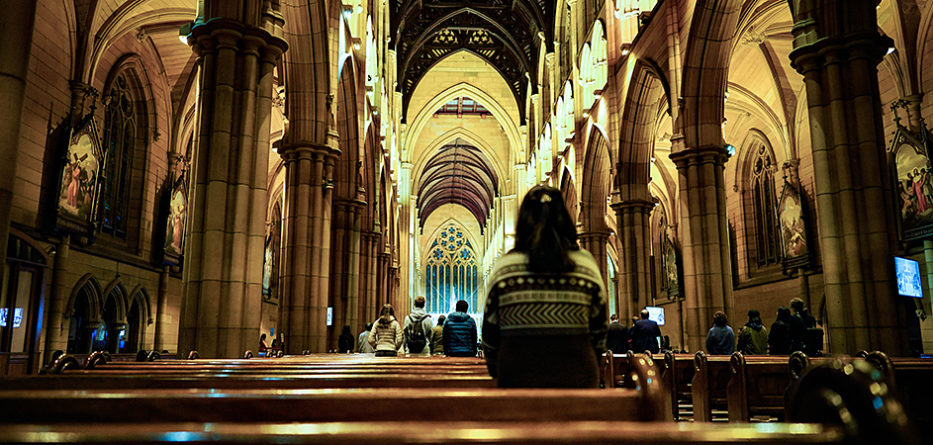

Central to Christianity is belief in life after death; resurrection after apparent failure; letting go so that something new can be discovered, the seed that dies in the ground so new life can grow. Death. Brings. Life. These themes are often repeated in the Word we hear together when we celebrate Eucharist, or in our own prayer. And yet even though we know the truth of this in our own lives, that God can make something new where nothing seems possible, as a Church community it seems that we fear letting go of what is, in order to discover what might be even more faithful and faith-filled.

Our Traditions and Scripture assure us that life is to be found in love, that freedom comes from letting go and that the truth will set us free. Jesus showed us what being his disciple looks like – healing, loving, forgiving, celebrating, proclaiming, walking among, withdrawing to pray, being community that acts out of love for the people and whatever binds them, and re-gathers for prayer and teaching. Jesus showed us he could let go, when the Syrophoenician woman challenged him and, profoundly in his death. The early Church is indeed a powerful example of letting go: no circumcision for Gentiles, including the excluded of the time, slave and free sitting together. Christianity was an alternative to the prevailing culture. Jesus showed us that God is on our side. With us. For us. Inviting us to fullness of life. Not like the Roman and Greek gods who needed placating and appeasing.

So, if this is all true, then two questions confound me: Why are we not brave? Not brave enough to let go and step out over the waves when everything in our faith tells us that is how we will find life in its fullness? I also wonder how it is that we people of faith seem not to trust that God is already there ahead of us, being light in the darkness, inspiring hope, love, forgiveness, justice and peace where they are needed? It puzzles me that we think we have everything to give the world, when the world already has Love. God is already present as Nostra Aetate[1] teaches. What would happen if we believed that?

God is to be found already active in this world of ours, rather than waiting for us to bring God to the world. How can it be that we ‘have God’ and others don’t?

You may be responding, but we have the Good News of Jesus Christ that the world needs. And that is true, but what is the Good News of Jesus Christ?

What is the Good News that the Church has to offer?

We offer nothing but the Good News of Jesus Christ.

Therefore, let us hear what he promised to give to us.

Jesus says to us in the Gospels: –

You are loved by God;

Your sins are forgiven;

You are free, even if you are slaves

You are healed in soul and mind

Your burdens will not crush you;

You will have peace in your heart,

beyond the peace that the world gives you;

You are called into God’s kingdom of peace and love;

You belong to me – no longer an outcast;

You are called to eternal life; and

You are redeemed, set free,

part of me

like the branches of a vine,

for all eternity.

Abstract from presentation made by Archbishop Barry James Hickey, Archbishop of Perth, General Relator of the Synod

Synod of Bishops from Oceania with Pope John Paul II in Rome 1998

This is the extraordinarily good news that our lives are more than they seem. What we see around us is this reality being lived way beyond the structures of the Church, in families, workplaces, neighbourhoods, social action, work for peace, practices of inclusion. Surely the difference is that we who gather as Church know who it is bringing this Good News to the world? Of course, the Church and individual people of faith contribute to that in amazing ways, but it is not only our domain. It is the domain of being human. That is what we celebrate. Whenever I use the Bishops’ statement with families, it brings them to life. It speaks in new words the ancient story of what God’s salvation means for us. It connects. Has impact. Creates energy and recognition that this faith makes a difference. It moves people visibly, like they are hearing the Truth for the first time. I am very grateful to the Bishops of Oceania for providing us with such a profound insight with which to engage new generations.

Every human life encounters mystery when we are touched by something more than we can see but intuitively feel, such as holding a child in need of comfort, watching a sunrise, or the stars at night, reconciling with someone. There are millions of daily and seemingly ‘ordinary’ ways, in which we encounter mystery, even if we are not fully conscious of what we are experiencing. In these moments we can sense that there is something more than is apparent. And every time this happens we are in touch with God’s grace; imminent, permanent, freely gifted to us.

If this is true, then it follows that God as mystery is at the heart of every human life, from conception to death. Being curious and uncovering how that mystery lives among us, is essential.

For example, when a family comes seeking Baptism, God is alive in them in their love as a family. What if we are curious about how they have encountered mystery, especially in this new life with which they are entrusted? Rather than feeling that people are asking for a Sacrament they don’t understand? What if we asked them to tell us what this child has meant coming into their lives? What are their hopes for this little one and their hopes for each other and the family? Why do they choose these godparents and why have the godparents said yes? Instead of programs trying to bring them up to speed on the Sacrament (which takes a lifetime to understand – being mystery), what if we walked them through the Baptism liturgy as a dialogue with their own encounters with mystery? The treasure is already in the field. What if we believed that the Sacraments don’t need protecting, but people do?

Part Two will be published tomorrow.

Catherine Whewell was Director of People in Ministry and Chancellor in the Catholic Archdiocese of Adelaide. Cathy now works as a leadership coach, specialising in social and emotional intelligence and managing conflict as the space of possibility, via Teams or Zoom or other forms of virtual communication.

[1] Nostra Aetate is the Declaration on the Relation of the Church with Non-Christian Religions of the Second Vatican Council. October 1965