Palm Sunday of the Passion of the Lord

Readings: Luke 19:28-40 (entrance); Isaiah 50:4-7; Psalm 21(22):8-9, 17-20, 23-24; Philippians 2:6-11; Lue 22:14 – 23:56

Sunday 10 April 2022

Breaking Open the Word

When we hear the word “memorial”, we think of an object that reminds us of a person from history or an event that took place many years ago. A war memorial for example. But the Jewish understanding of a memorial has a different meaning and sense to it. To them, the memorial is not just a remembering of past events now confined to history, but in a memorial celebration, the events of the past are brought forward into the present moment. Every time the Jewish people celebrate the Passover meal, they are not just remembering the events of the Exodus (when God led the people of Israel out of slavery in Egypt and into freedom), but every time they celebrate the Passover meal it is as if they are actually brought into contact with the events of the past. They are not transported back through time, but the events of the past are brought forward into the present moment; the events of the Exodus are made present in the hearts and minds of all believers.

It might seem a bit far-fetched, but we frequently apply this understanding of a memorial in our everyday lives. Remember a time in the past when someone did something that hurt us. The pain becomes real again in the present moment. So, that event, whatever they did to hurt us, is not an event confined to history if it is still able to hurt you in the present moment.

Born and raised in a Jewish family, Jesus was part of the Jewish tradition. When he celebrated the Passover meal—the Last Supper with his disciples—Jesus applied the same understanding of a memorial when he took bread and wine and said, “This is my body.… This is my blood” (Mk 14:22–24), “Do this in remembrance of me” (Lk 22:19. 1 Cn 11:24–25). The Twelve Apostles were also from Jewish backgrounds, so they would have understood the use of the word remembrance.

And so, whenever we gather for the celebration of Mass, we are not just remembering the events of the past—the Last Supper and sacrifice of Christ on the cross which took place some 2,000 years ago. We are not repeatedly sacrificing Christ over and over again, as if to suggest that the first time he gave up his life was not adequate. Instead, whenever we gather for the celebration of Mass, the events of the past are brought forward into the present moment—Christ’s sacrifice on the cross is brought forward into the present moment (CCC 1362–1366). And so, that sacrifice on the cross for the forgiveness of sins, his one great act of salvation and greatest expression of God’s love, is not an event stuck in the past or confined to history, but it is an event for all time, made available to all people, of every generation, whenever and wherever the sacrifice of the Mass is offered. When Jesus said, “Do this in remembrance of me,” he is saying to us that whenever you celebrate the Mass, whenever you remember me, I will be there with you, fulfilling the promise to be with us to the end of time (Mt 28:20).

During the Mass, in the Eucharistic Prayer, when the priest raises the Host and shows it to the people, and raises the chalice, saying, “Do this in memory of me,” it is as if Christ himself is being raised up on the cross before us. Effectively, Christ’s sacrifice on the cross and the sacrifice of the Mass are one and the same sacrifice (CCC 1367). The crucifix placed on or near the altar is a visual reminder to us of what is happening on the altar during the Mass. Jesus Christ is being raised up on the cross before us, and we are able to say that, not only did he give up his life for those who actually stood at the foot of the cross some 2,000 years ago, but we are able to say that this is what Christ did for me—this is what Jesus is doing for me during the celebration of Mass.

Fr Antony Jukes OFM

Artwork Spotlight for personal reflection

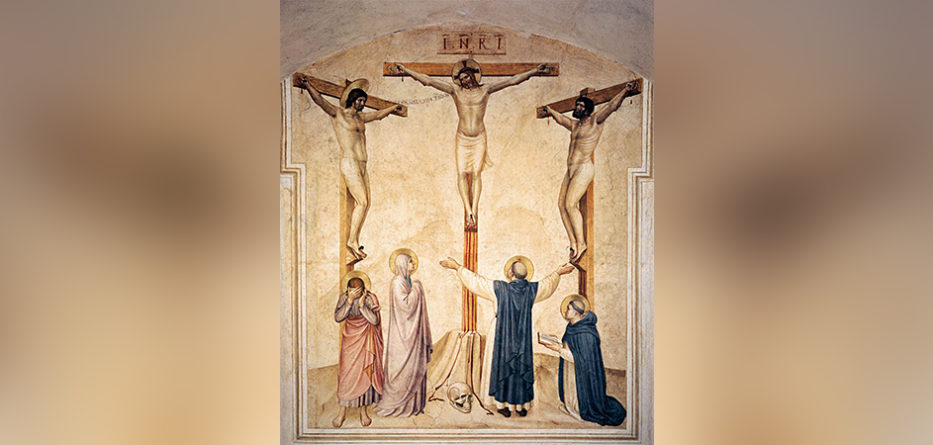

Crucifixion with Mourners and Sts Dominic and Thomas Aquinas (c. 1441−42) – Guido di Pietro. Known as Fra Angelico (1395-1445)

Crucifixion with Mourners and Sts Dominic and Thomas Aquinas (c. 1441−42). Fresco, 233 × 183 cm. Florence, church of S. Marco, upper floor, Dormitorium, cell Nr. 37 (north corridor of cells of the lay brothers), Florence, Italy. Public Domain.

“Jesus, remember me, when you come into your kingdom.” St Luke, the doctor, “softens” the crucifixion scene with this confession of the dying thief. While the leaders, the soldiers and the other criminal are mocking Christ as a false king and demanding he “save” himself, that is, come down from the cross, here is an unlettered outlaw professing Christ’s royalty before the mob. In response, Christ promises the man immediate salvation. In modern terms, we would call this a “plenary indulgence”. The Church gives every priest the power to stand in Christ’s name and repeat his words of forgiveness and promise to a dying Christian who acknowledges Christ as their King. God grant me a priest at the end!

This scene of the dying thief (by tradition called “Dismas”) gives us all great confidence. Thank you, St Luke, for leaving it with us.

“O the marvellous power of the cross,” says St Leo the Great. “No tongue can fully describe it. Here we see the judgment seat of the Lord” (Sermo 8 in Passione Domini). St John sees the cross as Christ’s throne from which he dispenses his honours list: the good thief is offered salvation, the executioners are granted forgiveness, and Mary is named Mother of all his disciples.

True to his custom of showing Jesus at prayer at all the important moments of his life, Luke (and only Luke) puts on the lips of Jesus as he dies the words of Psalm 31: “Father, into your hands I commit my spirit.” Happily, in recent times, lay people have become more familiar with the Psalter—the Church’s prayerbook. When we pray the psalms, we are uniting ourselves with Jesus and Mary, using the very words they prayed.

“Father, into your hands I commit my spirit.” “Our own hope is founded upon these words,” says St Cyril of Alexandria (+ 444). “For thanks to the goodness and mercy of God, we surely have every reason to be confident that, when they leave their earthly bodies, the souls of the saints are surrendered into the hands of a most loving Father. They do not haunt their tombs waiting for libations as some unbelievers imagine. Instead, they pass swiftly into the hands of the Father of all, along the way opened up for us by Christ our Saviour. He surrendered his soul into the hands of his Father to give us a firm faith and a sure hope that in him and through him we, too, shall pass when we die into the hands of God” (Commentary on St John’s Gospel, lib. 12).

Fra Angelico, an old friend of ours, specifically highlights the moment of the conversation between the good thief and Christ. Coming out of the mouth of Christ are painted, in Latin, the words he spoke, “Hodie mecvm eris in paradiso” (“Today you will be with me in paradise”)—upside down and back to front from the viewer’s point of view.

Our artist was born Guido di Pietro, probably about 1390–1395 near Florence. He initially received training as an illuminator, possibly working with his older brother Benedetto, already a Dominican. Just before 1423, Guido donned the habit of the Dominican Friars in the Convent of San Domenico at Fiesole (just outside Florence), taking the name of Fra Giovanni. “Fra Angelico” became current only in the 19th century.

In 1436, he was one of a number of friars who moved to the newly built Friary of San Marco in Florence. He enjoyed the patronage of Cosimo de’ Medici, one of the wealthiest and most powerful members of the city’s governing authority. Cosimo had a cell reserved for him at the friary so that he might retreat there from time to time. It was opposite Cell 37 which features this fresco of the crucifixion. The cell’s large size suggests it may have served as the chapel room for the lay brothers.

The fresco features a skull at the foot of the cross. It was once thought that Jerusalem was, at the beginning of time, the site of the Garden of Eden. Christ is the new Adam, reversing the sin of our first parents. Our Lady stands hands joined, contemplating her Son’s sacrifice, in complete contrast to John who weeps uncontrollably. St Thomas Aquinas kneels, his Summa Theologica in hand. Dominican lore tells us that St Thomas knelt before the crucifix to hear Christ say, “You have spoken well of me, Thomas.” St Dominic is depicted according to the witness of one of his contemporaries: “[He would] pray standing upright towards heaven as straight as an arrow shot from a bow, with his raised and joined hands extended strongly over his head…. [Imploring] God for gifts and graces for the Order.”

Mgr Graham Schmitzer

Fr Antony Jukes OFM was raised in a Catholic family in Chingford, East London (the second of six children.) He was an altar server at his parish for many years, but found himself drifting from his faith during his years at university. After completing his studies, he worked as a trainee-chartered accountant in central London. It was on a pilgrimage to the shrine of Our Lady of Lourdes (France) that led him to rediscover his love for his Catholic faith and to question his vocation. His devotion to St Antony of Padua, after whom he was named, and his love for St Francis of Assisi, led him to join the Franciscan Order of Friars Minor in 2002. He studied philosophy and theology at what was the Franciscan International Study Centre in Canterbury, England, before being ordained a priest in 2009. Having served in a parish and in a youth retreat centre, Fr Antony is now the novice director at the international novitiate community in Killarney, Ireland.

Mgr Graham Schmitzer is a retired parish priest in the Diocese of Wollongong. He was ordained in 1969 and has served in the parishes of Campbelltown, Gwynneville, Unanderra, Wollongong, Albion Park, and Corrimal. He was also chancellor and secretary to Bishop William Murray for 13 years. He grew up in Port Macquarie and was educated by the Sisters of St Joseph of Lochinvar, completing his leaving certificate at Wauchope High School. For two years he worked for the Department of Attorney General and Justice before entering St Columba’s College, Springwood, in 1962. Fr Graham loves travelling and has visited many of the major art galleries in Europe.

With thanks to the Diocese of Wollongong, who have supplied these weekly Lenten 2022 reflections from their publication, Remember – Lenten Program 2022.