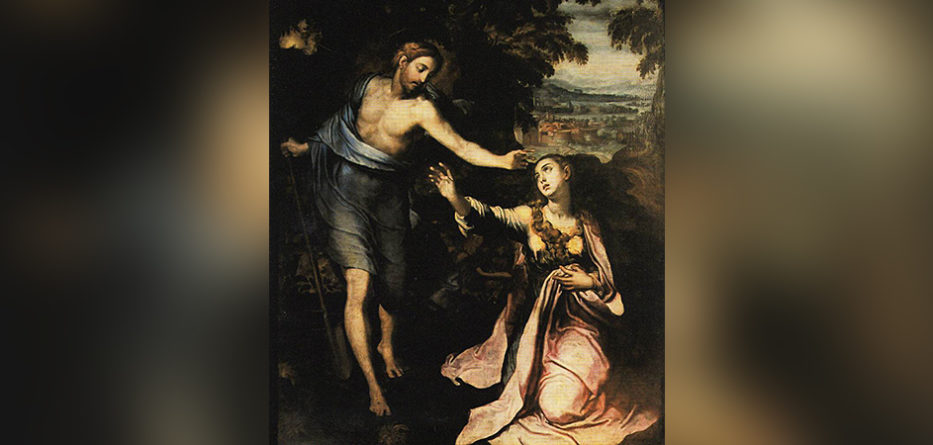

Mary Magdalene is a key figure in early Christianity. Present in the four Gospels, she occupies a unique position, being a privileged witness to the resurrection. The East loves to call her “apostle of the apostles.” Tradition very quickly made her, especially after the fourth century, a sinner and a prostitute, identifying her with anonymous women in the Gospels, such as the forgiven sinner of Luke 7:36-50. But nothing in the Gospels supports such an identification.

So, what do we know about her? Very little, in truth! She was from Magdala, a village on the shores of Lake Tiberias. Some interesting information is given to us by Luke when he gives us the list of women following Jesus from Galilee at Luke 8:1-3. Luke presents her within a group that is close to the Twelve: “There were with him the Twelve and some women who had been cured of evil spirits and infirmities: Mary, called Magdalene, from whom seven demons had come out; Joanna, wife of Herod’s steward, Chuza; Susanna and many others, who served them with their resources” (Luke 8:1b-3). This information is also found in Mark 16:9, with a variation of the verb used with regard to the demons (“Jesus appeared first to Mary Magdalene, out of whom he had driven seven demons”), but the vast majority of exegetes believe that the anonymous author of the canonical ending of Mark (described as “longer”) refers here to the text of Luke. Mary was therefore from Magdala and probably well-to-do and therefore independent.

According to Luke, she had been exorcised by Jesus. But why “seven demons”? Common sense, as well as the significance of numbers in the biblical tradition, makes us think that the diabolic possession was of an exceptional and dramatic intensity. Only one contemporary text, the Testament of Reuben, a para-testamentary text, mentions “seven spirits”: “Hear, my children, what I saw when I did penance concerning the seven spirits of deception; seven spirits were distributed to man, they are responsible for the misdeeds of youth” (Testament of Reuben, 2,1).[1]

What is certain is that the mention of the seven spirits is not a familiar reference at the time. Yet, Luke tells us shortly thereafter, and in the context of a controversy over his exorcisms, a parable of Jesus mentioning “seven spirits that were more evil” (Luke 11:26). Can a connection perhaps be made between these two texts, since they are the only mentions of “seven spirits or demons” in the entire Gospel? Many authors have been quick to do so. Thus one of the leading commentators on Luke, François Bovon, writes: “Possession by seven demons is, for Jesus, as in general for the Jews of his time, a particularly serious possession (the inauthentic conclusion of Mark’s Gospel, Mark 16:9, must depend on this recollection).”[2] Many cite this parallelism in footnotes, without going further.

The Spanish exegete Carmen Bernabé Ubieta insists above all on Mary’s socio-psychological dimension, but also points out the connection with Luke 11. According to her, “the seven demons can be interpreted as referring to a medical case that had been treated previously, but without success; the number of demons indicates a case in which […] the symptoms have returned and have become more virulent. This is what Luke 11:24-26 indicates.”[3]

One of the exegetes most convinced of the connection is the great Dominican biblical scholar of the last century, Marie-Joseph Lagrange. Commenting on Luke 8:2, he writes: “Possession by seven demons was particularly serious, and Luke will present it as a relapse (11:26), but not as the sign of a guilty life”; and, arriving at Luke 11:26, he continues: “The number seven is related to Mary Magdalene (8:2). The situation of those who are possessed is therefore not desperate in relation to the power of Jesus, but it is worse than before.”[4] If a connection can legitimately be established between these two passages, what does this mean on a literary and theological level? Does it add anything to our reading of Luke? Does it allow us to advance a hypothesis about Mary Magdalene’s role on Easter morning? This is worth exploring further.

The journey of Mary Magdalene in Luke

Mary Magdalene first appears at Luke 8:2. Her first characterization is twofold. On the one hand, she is part of the group of disciples, a group of women “who had been healed of evil spirits and infirmities” – which is positive – and, moreover, she had seen “seven demons” come out of her (the same verb that is used in Luke 8:38 for the possessed Gerasene man, from whom a legion of demons came out) – which, at first glance, is more ambiguous. However, it should be noted that all these women were possessed or sick. In this perspective, Mary is not unique. Prior to these women, other people had been exorcised in the third Gospel (cf. Luke 6:18 and 7:21). None of the twelve apostles, however, had been freed – or healed – by Jesus. It therefore seems that the twelve disciples came to him not primarily to be healed or exorcised, but for other reasons. What attracted them was his word, rather than his healing power; messianic hope, rather than a desire to be freed from demons. But there is certainly a strong element of affectivity in this desire, and we must be careful not to label it too quickly or to conflate the two motivations. This is not to pit the male disciples against the female disciples, but simply to note that the apostles, future witnesses to the resurrection, had not experienced the power of God acting through Jesus in their bodies, unlike the women mentioned in Luke 8:2.

Luke seems to imply that physical healings have a psychological or demonic dimension (cf. Luke 8:27,29-30,35, and also Luke 4:33-39). To affirm that in the case of the women, and therefore of Mary Magdalene, it is a question of the “body,” of healings of a physical nature, is not to set “body” and “spirit” against each other or to imply that exorcism does not involve the spirit or the soul. And vice versa. Things are intertwined, especially in Luke. Thus, it does not seem irrelevant that these women wanted to take care of Jesus’ body. Beyond the fact that, culturally, it was up to women to perform funeral rites and take care of bodies,[5] it seems plausible to think that these women, healed in their body and spirit, had a stronger attachment to the very body of Jesus.

Mary Magdalene in fact disappears from the narrative, along with the women who were with her, only for her name to reappear in Luke 24:10. However, the verses at Luke 23:49 – “All his acquaintances, and the women who had followed him all the way from Galilee, stood at a distance watching all this” – and at Luke 23:55 – “The women who had come with Jesus from Galilee followed Joseph; they watched the tomb and how Jesus’ body had been laid” – necessarily referring the reader back to the list at Luke 8:2-3, emphasizing the importance of these passages more than the reader might initially suspect.

The repetition of verse 55 of Luke 23, so close to verse 49, is quite strong and insistent. The women who go to the tomb (cf. Luke 24:1-8) are not named at first, but Luke relates their names shortly thereafter: “They were Mary Magdalene, Joanna and Mary the mother of James. The others who were with them also told these things to the apostles” (Luke 24:10). The list clearly refers back to the previous one, especially since Luke 23:49,55 reminded us that the women were following Jesus from Galilee. These are not, therefore, women who became disciples at the last hour. Two of the three names are in common: Mary and Joanna. But the latter is found only in Luke and not in the other Gospels. This list therefore takes away part of the uniqueness of Mary of Magdala. In fact, in this way she is not the only one recorded as a witness of the resurrection according to the criterion that will be indicated at the beginning of Acts (given as a fact for the “men”: Acts 1:21). Having accompanied Jesus “beginning from the baptism of John until the day when he was taken up from us into heaven” (Acts 1:22). Mary of Magdala belongs to a group of women.

She is in a sense established as the leader of a series of women, of whom only a few are named. She is therefore a discreet but fundamental figure. She is present in only two episodes of Luke’s Gospel, and her words are not communicated to us. She bears witness, as do other women, but their words are not believed (cf. Luke 24:11). The fact that these women had been at the tomb immediately after the Passion and on Easter morning gives them a decisive importance in Luke’s account, an importance which is necessarily reflected in their first appearance in the Gospel narrative. Now it is surprising that, of the only two women named in the two episodes, one is qualified socially by the status of her husband: “Joanna, wife of Chuza, Herod’s steward,” and the other, Mary, is qualified only by a deliverance, a successful exorcism. The first, Joanna, is included in the group of notables, such as, for example, Joseph of Arimathea. The second, Mary, is a disciple who has been “healed” or, more precisely, “liberated.” The Twelve were called, but they were not healed. Mary is thus constituted as the only person witnessing the resurrection of whom we are expressly told that she was set free or healed by Jesus.[6] Considering the importance of the resurrection in the structure of the narrative, this fact cannot be secondary.

An intratextual echo

Is this juxtaposition of Luke 11 with Luke 8 justifiable? Antiquity, both Jewish and pagan, knows that when two different passages contain the same rare word or expression; they can be connected by reasoning to clarify one of them or to explain one through the other. Then again, this is an elementary principle of hermeneutics. Identifying such parallelisms was clearly not unknown to Greek grammarians and Hellenistic literature, and Luke’s work clearly fits into a Hellenistic framework. Homer’s epics were a privileged area of study for this kind of research. An author – ancient or modern – can thus leave clues for future readers by using the same expression twice to make connections between two passages.

Both Luke and John make connections between episodes with the repetition of a rare term. It may be noted that one such term, “charcoal fire” (anthrakia) is found only in John 18:18 and John 21:9, thus creating an obvious parallelism between the threefold denial and the threefold confirmation of Peter’s mission. The semantic aspect reinforces a connection already evident to the reader. In Luke, a rare verb, “compel” (parabiazomai), used in the account of the Emmaus disciples’ encounter with Christ in Luke 24:29, is taken up in the account of Lydia’s encounter with the apostles Paul and Silas in Acts 16:15. Thus the reader is encouraged to establish a connection between the two passages and to realize that to welcome an apostle is to welcome Christ himself.[7] The echo is more subtle, but nonetheless theologically consistent.

This method works for single words, but also for semantic sets of two or more words. Thus the specialist of the historical Jesus, John P. Meier, explains how Jesus was able to connect Deut 6:5 and Lev 19:18, both of which contain (and they alone, if we consider that Lev 19:34 concerns the foreigner, therefore also a human being) the syntagma “you shall love” followed by the particle that introduces the object.[8]

Other expressions are used in this way in Luke’s work to create parallelisms between the Gospel and Acts, between Jesus and his apostles. Thus Luke 6:18 says of Jesus that “those who were tormented by unclean spirits were healed.” And Acts 5:16 says, in reference to Peter, that “the crowds from the towns near Jerusalem also came, bringing sick people and those tormented by unclean spirits.” Even more clearly, when Jesus raises the son of the widow of Nain, it is said of the young man, “The dead man sat up” (Luke 7:15); likewise, when Peter raises Tabitha, the verse ends with “and she sat up” (Acts 9:40).

Is it possible to find this process at the very heart of the Gospel? A good example is provided by what Zacchaeus declares after his encounter with Jesus: “If I have stolen (esykophantēsa) from anyone, I will give back four times as much” (Luke 19:8). His words echo a rare verb found in John the Baptist’s admonition to the soldiers in Luke 3:14: “Do not mistreat or extort (sykophantēsēte) anything from anyone.” Jesus continues the work of the Baptist: this is one of the major parallelisms (synkriseis) of Luke’s Gospel. These semantic echoes are illuminating.

In our case, we are dealing with the indication, in Luke 8:2, of “evil spirits” (which were mentioned in the plural only in Luke 7:21, in a list) linked to the number “seven,” and followed immediately by “seven demons” (in the same verse of Luke 8:2), which are echoed by “seven” “worse” spirits in Luke 11:26.[9] Why does Luke not use the expression “seven demons” directly in Luke 11:26? According to traditional views, the passage in Luke 11:24-26 belongs to the source of the logia, because it is also found in Matthew (cf. Matt 12:43-45). And it is known that Luke is usually quite faithful when referring to such a source. It seems that the expression “seven spirits,” spoken by Jesus, is more Semitic and original than “seven demons.” Having chosen to retain it, Luke also takes it up at Luke 8:2a, so that the parallel appears clearly, though using, in Luke 8:3, the more Greek syntagma of “seven demons.” But it cannot be said that one of the passages uses exclusively “evil spirits” and the other “demons,” for it can be noted that the pair “demons”/“evil spirits” is found equally in the whole of Luke 11:14-26, where the term “demons” is used repeatedly in the controversy around Beelzebub (cf. Luke 11:14,15,18,19,20). The third evangelist shows a preference for the word “demons,” which he uses, for example, in Luke 13:32, in a pericope of his own, but he does not ignore the other term.

Ancient exegetes, whether Jewish or Greek, gave weight to these repetitions of syntagma’s in explaining sacred texts. But even an ordinary reader, if reading carefully, can recognize such verbal repetitions. In order to justify a comparison between Luke 8:2 and Luke 11:26, however, we need to see whether this observation helps to make sense of such a comment about Mary Magdalene on a literary and theological level. For it is here, after all, that the validity of such an observation is to be found.

Jesus and the leader of the demons in Luke 11:24-26

Luke, like Matthew, relates the parable of the strong man and the seven demons (cf. Luke 11:24-26 and Matt 12:43-45) shortly after an exorcism by Jesus, followed by a controversy with the Pharisees (cf. Luke 11:14-22 and Matt 12:22-32). But while Matthew inserts two independent pericopes between them, Luke maintains a strong link between them. This passage is one of the most significant in the Gospels for showing Jesus’ struggle with the devil. Because of the rare and striking expression, found only in Luke, “if I cast out demons with the finger of God” (Luke 11:20), Meier is led to recognize the authenticity of this tradition.[10] It should be noted that this author, in the same volume, cautiously pronounces in favor of the historicity of Mary Magdalene’s possession, for the very fact that this detail tends to discredit her testimony about the resurrection, as Celsius will later claim.[11]

But, beyond the strictly historical question, which for us here is secondary, we believe that, thanks to the mention of the “evil spirits” and the “seven demons” in Luke 8:2, Luke has created a strong link between the scene – which could be considered the most spectacular – of Jesus’ struggle against the demons and the figure of Mary of Magdala. The juxtaposition generated by the use of the unique expression “seven demons” creates an effect of explanation. Certainly the syntagma “seven demons” is not found in Luke 11, but there we have “the evil spirits,” which are mentioned in Luke 8:2b. The reader of Luke 8 spontaneously makes the connection between the “evil spirits” of 8:2a and the “seven demons” of 8:2b: and therefore understands that these seven demons were evil spirits present in numbers of seven, but could go no further. The enigmatic mention at Luke 8:2b then acquires a new value and its relevance is clarified.

The parallel suggests that Mary had been freed a first time – by Jesus or another, it matters little in the final analysis – and that she had been possessed again. This means that what Jesus says about the human being in Luke 11:26b applies to her: “And the last condition of the human being becomes worse than the first,” where it should be noted that Luke here uses the term “human being” (Anthropos) and not the term “man” (aner). Nothing is said about the guilt of such a person, because we are not in a context of explicit sin. But, in the face of this serious fall indicated by the pericope, a question immediately arises: Is this defeat definitive? Is it still possible to hope? Is God therefore definitively defeated by the devil? The silence that follows Jesus’ final affirmation is heavy. At this level of the story, it is the verse from Luke 8:2 that comes to the reader’s aid. It indicates that it is possible to overcome even the seven demons and that Jesus did so at least in the case of one person, a woman: Mary Magdalene. The two passages clarify and enrich each other.

The fight against the devil in Luke

Another element to be taken into consideration in order to ground the hypothesis of the link between the two passages is that of the importance of exorcisms in Luke. It is often observed that the third evangelist is very interested in diseases and possessions.[12] Moreover, this fact has long given credibility to the theory that the author of the Acts of the Apostles was Luke, the “dear physician” mentioned in the letter to the Colossians (cf. Col 4:14). In Luke-Acts we find healings involving evil spirits or showing their activity in greater numbers than in the other evangelists; the following cases are specific to Luke: Luke 10:17-19; 13:31-34; 22:3; 22:31-34. Therefore, a mention of demons cannot be, for Luke, anecdotal or simply a remnant of earlier tradition, uninteresting a priori. On the contrary, exorcism is at the heart of Jesus’ mission. It is a sign of the coming of the power of the Kingdom and the defeat of Satan. Since the resurrection is clearly a revelation of the power of God and the concomitant defeat of Satan (who had entered Judas to make Jesus die: cf. Luke 22:3), there is an analogy between the victory won by God and his Messiah over the demons present in Mary Magdalene and the victory won in a dazzling way by the resurrection. The partial victories achieved over the demon during the public ministry had indicated the power of God at work in Jesus and prepared for the revelation of that power at the end of the narrative.

It is also natural that this saving power is entrusted to the disciples during their public ministry (cf. the passage, proper to the third Gospel, from Luke 10:17-20: “Even the demons submit to us in your name”) and continues to be at work in the Acts of the Apostles. In fact, this struggle does not end with the Gospel, but continues in Acts, where we meet Paul the thaumaturge. In Acts 16:16-24, the apostle releases a woman who had a “spirit of divination,” which he expels “instantly” (Acts 16:18). Another comparison is revealing. In Acts 19:11-13 we are told, as with Jesus in Luke 8:1, that Paul healed many sick people and that handkerchiefs touched by him healed and cast out “many evil spirits,” an expression repeated in verses 12 and 13. The account continues (Acts 19:13-17) with a comparison to some Jewish exorcists. These are the “seven sons” of a high priest named Shevah, which means “seven” in Hebrew. The number “seven” is strongly emphasized! The connection of this number with issues of life and death is found in the book of Tobias, where Sarah’s “seven” husbands were killed by Asmodeus, “the evil demon” (cf. Tob 3:7-8).

After having suffered the oppression of the seven demons and having been freed, Mary Magdalene is not discredited by this information given about her, as some commentators who want to highlight the alleged misogyny of Luke point out,[13] but becomes, on the contrary, more credible. Mary is part of the struggle waged by God against Satan, of which Jesus was the spearhead. Restored to her human integrity, healed “body and soul,” as the common expression goes, she is a partial anticipation of the total liberation from which Jesus will benefit (just as Lazarus in a certain way anticipates in part the resurrection of Jesus in John) and which, in turn, anticipates the liberation of humanity.

The eschatological and apocalyptic dimension of the struggle against Satan runs through the entire Gospel of Luke: the repeated confrontations of a character like Mary Magdalene with demons cannot simply be anecdotal. Nor can the fact that the only information provided about her refers to her status as a person liberated from possession. Mary of Magdala embodies a liberated humanity.

Luke, evangelist of hope and mercy

It is often said that Luke is the evangelist of mercy, and there are many clues to that effect. This is clearly an important theme in Luke’s Gospel. But what connection can be made between this impressive theme and the secondary mention of the “seven demons”? Jesus’ parable in Luke 11 is one that warns and, in a sense, threatens. The demon, once cast out, can return and, when it returns – or rather, when it returns in the company of its fellows – the situation is worse than before. This means, moreover quite understandably, that casting out demons a second time is a more difficult task. The second passage in Luke leads the reader to understand that Jesus had already exorcised a woman, Mary of Magdala, who then relapsed into a worse possession than before. The reader cannot yet know the importance this woman will have for the conclusion of the story, but does take note.

As we have already observed, Luke does not say whether the first exorcism was performed by Jesus himself. After all, he clearly states that Jesus was not alone in performing exorcisms (cf. Luke 11:19). But in a sense this question is secondary. It seems to us that, taking into account Luke’s Christological perspective, it is more probable that Jesus had also performed the first exorcism. By freeing Mary Magdalene a second time, he would have shown at the same time his power, received from the Spirit, and his mercy. But, even in the less likely case that it was not Jesus who performed the first exorcism, the point is that he had consciously freed a woman who was again possessed, defeated a second time by the demon, or demons. Jesus did not declare himself defeated. He fought to the end.

In the pericope on forgiveness, which Luke shares with Matthew, the third evangelist has a different formulation. Matthew writes, “Then Peter came to Jesus and asked, ‘Lord, how many times shall I forgive my brother or sister who sins against me? Up to seven times?’ Jesus answered, ‘I tell you, not seven times, but seventy-seven times’” (Matt 18:21-22). Luke, for his part, writes: “Even if they sin against you seven times in a day and seven times come back to you saying ‘I repent,’ you must forgive them” (Luke 17:4). Thus, the number “seven” expresses a culmination. a culmination in alienation or a culmination in forgiveness. Of course, one cannot formulate a pure and simple identification between sin and possession.

On the other hand, it must be recognized that Luke “blurs the line between healing and demonic activity more than any other New Testament writer,” as John Thomas rightly points out.[14] It may be added that the third evangelist “is the only New Testament writer to use the expression ‘evil spirits’ (Luke 7:21; 8:2; Acts 19:12, 15-16).”[15] One can also consider the well-known episode of Peter’s mother-in-law, in which the healing is presented by Luke as an exorcism (cf. Luke 4:38-39). But in both cases – illness or possession – it is up to Jesus to fight against the evil of which Satan is an accomplice. Sickness, possession and, sometimes, sin go hand in hand, for all three express the burden that weighs on humanity, and those affected by them call for the coming of a savior (cf. Luke 2:30 and Acts 28:28).

The importance given to the figure of Mary Magdalene does not, however, place her on a pedestal, and the references to her are sober. It is observed that at the same time Luke establishes a second woman as an eyewitness, Joanna. If the evangelist accords an important place to the Twelve and Peter, he also reserves for Cleopas and his companion, who are not part of the Twelve, his great post-Easter scene. Similarly, if he gives an eminent place to Mary Magdalene, he also wishes to include her in a larger group of women.

Conclusion

The beneficiary of salvation in a super-eminent way, it was fitting that Mary Magdalene should also be the proclaimer of salvation in a unique way. She, who had been liberated body and soul twice, was able to perceive more than anyone else that a person who had distinguished himself to such an extent in his struggle against death could not be so easily defeated; that the power of God could free the body of Jesus from the prison of death. In this way Mary Magdalene became a double witness: a witness to the power of God in overcoming death in the very heart of life – which she had experienced in Galilee – and a witness to the power of God in overcoming the seeming finality of death, the defeat of the cross. Mary of Magdala had not despaired in Galilee, and she will be the first to hope in Judea. There is thus a profound coherence between the indication given about her person in Luke 8:2 and her status as a privileged witness to the resurrection in Luke 24:9-10.

Reproduced with permission from La Civiltà Cattolica and Marc Rastoin SJ.

DOI: La Civiltà Cattolica, En. Ed. Vol. 5, no. 5 art. 16, 0521: 10.32009/22072446.0521.16

[1]. Cf. A. Dupont-Sommer – M. Philonenko (eds), La Bible. Écrits intertestamentaires, Paris, Gallimard, 1987, 818.

[2]. F. Bovon, L’Évangile selon saint Luc. 1,1-9,50, Geneva, Labor et Fides, 1991, 390.

[3]. C. Bernabé Ubieta, “Mary Magdalene and the Seven Demons in Social-scientific Perspective”, in I. R. Kitzberger (ed), Transformative Encounters. Jesus and Women Re-viewed, Leiden, Society of Biblical Literature, 2000, 219.

[4]. M.-J. Lagrange, Évangile selon Saint Luc, Paris, Gabalda, 1921, 236 and 335.

[5]. Cf. K. E. Corley, Maranatha. Women’s Funerary Rituals and Christian Origins, Minneapolis, Fortress, 2010.

[6]. It is most likely that Mary is joined by Joanna, but the wording of Luke 8:1-3 could make the latter primarily a disciple helping Jesus with her resources (given her husband’s status).

[7]. Cf. M. Rastoin, “Cléophas et Lydie: un ‘couple’ lucanien hautement théologique”, in Biblica 95 (2014) 371-387.

[8]. Cf. J. P. Meier, Un ebreo marginale. Ripensare il Gesù storico. Vol. 4: Legge e amore, Brescia, Queriniana, 2009, 487-520.

[9]. The expression “evil spirits” is therefore present in Luke’s Gospel three times, in a sort of progression: 7:21; 8:2; 11:26 (“worse spirits”).

[10]. Cf. J. P. Meier, Un ebreo marginale. Ripensare il Gesù storico. Vol. 2: Mentore, messaggio e miracoli, Brescia, Queriniana, 2002, 478-502.

[11]. Cf. Origen, Contra Celsum, 2, 55, in which the author quotes Celsus speaking of a “half-crazed” woman.

[12]. Cf. T. Klutz, The Exorcism Stories in Luke-Acts: A Sociostylistic Reading, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2004.

[13]. Cf. E. Lupieri (ed), Una sposa per Gesù: Maria Maddalena tra antichità e postmoderno, Rome, Carocci, 2017, 25. The book cites several authors who tend in this direction.

[14]. J. C. Thomas, The Devil, Disease, and Deliverance: Origins of Illness in New Testament Thought, Sheffield, Sheffield Academic Press, 1998, 225.

[15]. “[He] is the only writer in the New Testament to use the term ‘evil spirits’ (Luke 7:21; 8:2; Acts 19.12.12.15-16)” (ibid).